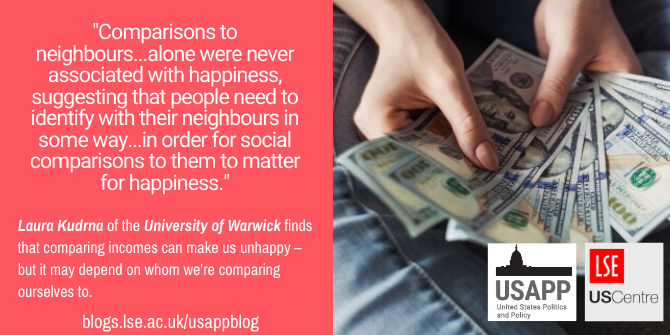

Subjective reports of wellbeing or ‘happiness’ are increasingly influential in policy. While past research has found that making comparisons with those on higher incomes can make people unhappy, Laura Kudrna illustrates that this ‘relative income’ effect may not be as straightforward as previously thought, with the structure of society having an impact on how people feel and think about their lives.

Subjective reports of wellbeing or ‘happiness’ are increasingly influential in policy. While past research has found that making comparisons with those on higher incomes can make people unhappy, Laura Kudrna illustrates that this ‘relative income’ effect may not be as straightforward as previously thought, with the structure of society having an impact on how people feel and think about their lives.

In happiness research, the ‘relative income effect’ typically refers to the finding that the higher the income of one’s neighbours or peers, the less happy one feels as a result. A leading explanation is that people compare upwards to those who are doing better than them, and then they feel worse about themselves as a result of looking up to those who appear to have achieved more. Such a result suggests that economic growth can have costs for happiness, especially when it is not evenly distributed.

Detractors might argue that people should stop making comparisons to others, and simply ‘get over it’. Psychological research is clear that it is not so simple. People make comparisons automatically and unconsciously – that is, it is difficult not to make comparisons to what others have, and this can impact how people feel regardless of whether or not they stop and think about the fact they are making a comparison. Income is used to proxy consumption in this literature, and much consumption is visible, thus, there are ample opportunities to compare to how well others are doing and to feel worse when we don’t measure up.

Not all studies find that relative income matters for happiness. Some studies even find a positive effect of others’ higher income, such as in local neighbourhoods and transition economies. Positive effects can be explained by resource sharing within groups or the idea that people use others’ income as a signal about their own future prospects. The latter explanation is known as the ‘tunnel effect’ – if I am stuck in a traffic jam in a tunnel, and the traffic starts to move ahead, I can be pretty sure that I’ll soon be on my way, too.

Photo by Alexander Mils on Unsplash

One of the issues that crops up in past studies is that ‘reference groups’ are not consistently defined. Whose income and consumption are people aware of and making comparisons to, exactly? A good answer cannot be found simply by asking people to whom they make comparisons, partly because – as above – comparisons can occur below conscious awareness and yet still have an impact. Existing measures of what I call the ‘scope’ of reference groups are diverse and include geography (zip-code, county, state, world), colleagues, friends, ‘ideational’ reference groups such as religious or political affiliation, and those defined based on demographics such as marital status, age, and gender.

In addition to these scoping issues, variation also exists in how information about income within a reference group is summarised. Is it an average income within a group? Median? What about the proportion of those with ‘high’ incomes? Does an individual’s standpoint within a reference group matter – should we look at rank, or distance from the average or median? It can be difficult to compare across studies because of differences in scopes (neighbours, colleagues) and summaries (average, proportion rank). To know how relative income influences happiness, more clarity about what relative income means is needed.

In my PhD thesis, I wanted to find out how such issues affected the conclusions reached about the effects of relative income on happiness. I created and analysed over 300 different measures that captured different sorts of reference groups and relative effects for income, as well as education and unemployment. These 300+ measures were used in nearly 4,000 models across two datasets – one from the United States and another from the United Kingdom. The results were adjusted for multiple comparisons. What were the findings? Upward comparisons to others’ higher income did appear to matter for happiness, and the effect was almost always negative. However, comparisons to neighbours (in states and local authorities) alone were never associated with happiness, suggesting that people need to identify with their neighbours in some way (such as age) in order for social comparisons to them to matter for happiness.

These are many caveats to these results, such as the difficultly of establishing causality and the reduction of complex constructs like happiness into quantitative assessments. When considering subjective reports like happiness as measures of wellbeing, there is the important issue of happiness across generations, which happiness research does not generally address. What this generation does has consequences for the next; however, the next generation does not yet exist and so they are absent from our analyses of happiness. Nevertheless, with happiness research being taken seriously by policymakers across the political spectrum, it is important for us to consider the implications of the findings.

The implications are not straightforward and can be controversial. In my work, I provided evidence to inform discussions about the optimal level and distribution of resources in society, rather than to directly determine what, if anything, should be done. We do know that happier people are healthier, take fewer risks, are more productive, more creative, and better at solving conflicts. Recent research also shows that happiness is a predictor of voting behaviour. If we care about these outcomes, we should care about the societal conditions that drive them.

- This article is based on Dr Laura Kudrna’s LSE PhD thesis, ‘Please award this degree, even though it is likely to make others miserable – and me too’.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/37wnQud

About the author

Laura Kudrna – University of Warwick

Laura Kudrna – University of Warwick

Dr Laura Kudrna is a Research Fellow at the University of Warwick Medical School.