In the 2016 election, rural voters broke for Donald Trump, while voters in cities voted for former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. As the 2020 election approaches, will Democrats be able to make inroads with rural voters? Using survey data on rural resentment, Jack Thompson finds that most rural voters have a negative view of candidates running in the Democratic presidential primary, with Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders being the least unfavored.

The 2016 US Presidential election highlighted a growing rural-urban schism. The trend of rural polarization in the US is such that Republicans are strengthening their dominance in rural and small-town America. Conversely, the Democrats continue to dominate urban locales along the Coasts. The increasing rural-urban divide also has important implications for future US elections, and especially the upcoming 2020 Presidential election in November. It is useful to consider the nature of the US Electoral College in this context; while it was designed as a bulwark against an excess of popular will, it is also intended to give states with small populations a voice in the Presidential election. In recent elections, the Electoral College has spelled doom for Presidential candidates with urban-based voter coalitions. If the Democrats are to avoid a repeat of Clinton’s loss in 2016, the very nature of the US electoral system means that they must reach out beyond their urban bases.

The current debate concerning 2020 Democratic electoral strategy is just this. On the one hand, there are those who believe that states like Iowa, that Obama won by 9.1 points in 2008 but Trump won by 9.2 points in 2016 are now out of reach. On the other hand, an increasing number of Democratic strategists recognise that, in swing states like Wisconsin where Trump won by a few thousand votes in 2016, focussing on issues such as the impact of tariffs on agriculture will make all the difference in winning rural voters in those states back.

Importantly, however, the rural-urban divide is not only a geographic one. It is also temporal. This divide is best articulated in rural ethnographies that explore the distance that many rural Whites feel between themselves and those who live in cities and Washington D.C. In her landmark 2016 ethnography of rural Wisconsin, Professor Katherine J. Cramer of the University of Madison-Wisconsin calls this temporal divide rural consciousness. Rural consciousness is a robust form of group awareness rooted in class and the importance of place. It is underpinned by the belief that rural areas are ignored by the government, that those living in rural areas do not get their fair share of resources, and that rural Americans have lifestyles that are fundamentally distinct from those who live in cities.

The most recent pilot University of Michigan/Stanford University American National Election Study (ANES) contains a few important items concerning Americans’ attitudes towards rural America. Importantly, among them are several items concerning rural resentment, which I operationalise into a statistically measurable construct here for the first time using the ANES Pilot data. Consistent with Cramer’s original ethnographic design into the ethnographic study of predominately White rural and exurban communities in Wisconsin, I focus on a subset of just under 1,000 White Americans who reported living in a rural area or a small town. My aim here is to show how rural resentment feeds into Whites’ evaluations of well-known political figures, including most of the major candidates for the Democratic nomination. I do this to see which of the candidates – if any – rural Americans have the most favorable estimations of relative to President Trump.

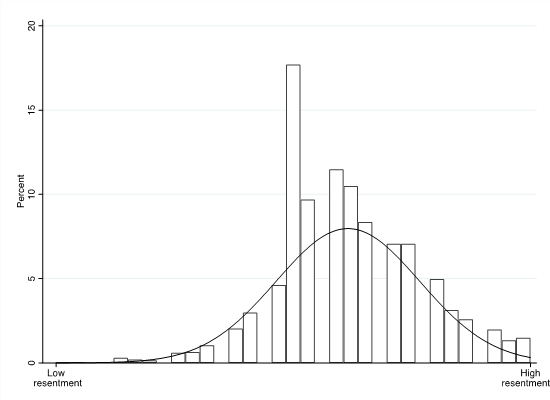

Before I turn to discuss how people feel about the candidates, it is useful to explore the pervasiveness of rural resentment among rural and small-town Whites. Figure 1 shows the distribution of rural resentment (rescaled to range from 0 to 1) among the subsample. As the figure shows, rural and small-town Whites skew in the resentful direction; the curve is displaced from the centre and slopes towards high resentment.

Figure 1 – The Distribution of Rural Resentment Among Rural and Small-Town Whites

Just how popular are the current slate of candidates for the Democratic nomination among rural and small-town Whites? Figure 2 plots affective evaluations of (how people feel about) a number of political figures (asked on the standard feeling thermometer where 0 = “very cool or unfavorable feelings; 100 = “very warm or favorable feelings”) across levels of the rural resentment scale. For comparability, I also include thermometer ratings for President Obama and President Trump.

Photo by specphotops on Unsplash

Figure 2 highlights the problem that the Democrats are facing in rural and small-town America in November. Increasing rural resentment is associated with cooler feelings towards all the major Democratic 2020 Presidential candidates. Despite this general trend however, not all Democrats are affected in the same way. For instance, respondents low in rural resentment give Former Vice President Joe Biden a thermometer rating of 49/100 and moving from low resentment to high resentment is associated with a decline in warm feelings of 17 points. Contrastingly, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders experiences an 11-point decline in his thermometer ratings moving from high resentment to low resentment.

Figure 2 – Thermometer Ratings of Political Figures as a Function of Rural Resentment

Notes: Dependent variables are thermometer ratings of political figures. OLS models control for racial resentment, assessments of personal financial situation and national economic trends, political interest, partisanship, ideology, gender, age, education, income, Evangelical status, region, and community size. All covariates are set to their respective means. Shared areas represent 95 per cent confidence intervals. Sample limited to non-Hispanic White Americans living in a rural area or small town. Data are weighted.

My analysis of the ANES data show that some candidates for the Democratic nomination are received better than others in rural and-small town America. While Sanders is the best received of any Democrat among rural and small-town Whites, it is important to note that estimations towards the Vermont Senator are still unfavorable. The data highlights the uphill struggle that the eventual Democratic nominee will face in trying to appeal beyond their urban base if they are to win back crucial swing states with large numbers of rural Whites such Wisconsin.

Given Trump’s popularity in rural and small-town America, the question of rural strategy for the Democratic Party is not whether they can win these areas, but whether they can appeal to enough of these voters in crucial swing states where the margin of victory was extremely tight in 2016. Issue such as healthcare and local infrastructure are important to many rural Americans, and an emphasis on these policies might prove successful in mobilizing the minority of rural Americans who disapprove of President Trump to make the difference in states like Wisconsin.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2IoJmqC

About the author

Jack Thompson – Nottingham Trent University

Jack Thompson is a PhD student at Nottingham Trent University researching American politics and White American voting behaviour. His thesis project examines the predictors of White American voter choice for President in the 2016 US presidential election.

1 Comments