The Covid-19 crisis is causing global disruption, with the US far from immune. Peter Finn and Robert Ledger sketch out how the crisis is, and could, affect the ongoing primary process and the presidential election in November.

The Covid-19 crisis is causing global disruption, with the US far from immune. Peter Finn and Robert Ledger sketch out how the crisis is, and could, affect the ongoing primary process and the presidential election in November.

- This article is part of our Primary Primers series curated by Rob Ledger (Frankfurt Goethe University) and Peter Finn (Kingston University). Ahead of the 2020 election, this series explores key themes, ideas, concepts, procedures and events that shape, affect and define the US presidential primary process. If you are interested in contributing to the series contact Rob Ledger (ledger@em.uni-frankfurt.de) or Peter Finn (p.finn@kingston.ac.uk).

Disruption to the primary calendar

On March 13th, Louisiana’s Governor John Bel Edwards suspended his state’s presidential primary from April 4th until June 20th. According to Edwards’ spokesperson, the suspension in the Pelican State, where at the time, three dozen Covid-19 cases had been confirmed, was ‘necessary to protect the health and safety of the people of Louisiana’. In similar moves, Georgia has also moved its primary to May, while the postponement of the Ohio Primary caused tensions between Governor Mike DeWine and the state’s judicial branch. Given the speed with which the virus is spreading, and the fact the US Centre for Disease Control (CDC) has advised against public gatherings of more than 50 people, it would be a surprise if more disruption to the primary calendar did not occur. The face to face part of the caucus in Wyoming, scheduled for April 4th, for instance, has been suspended.

Disruption to conventions

Both the Democratic and Republican Party’s national conventions are huge events drawing thousands of people from across the country, especially so for those where presidential candidates are nominated. However, the CDC guidelines advising against gatherings larger than 50 are currently scheduled to remain in place until mid-May. Yet, it would not be surprising if some element of these restrictions stay in place for significantly longer. The Democratic convention is currently scheduled to occur at the Fiserv Forum in Milwaukee in mid-July, with the Republican convention scheduled for late August at the Spectrum Center in Charlotte, North Carolina. If even a watered down version of the CDC guidelines remain in place come summer, it is hard to see how they would be compatible with holding either convention.

Procedurally, this is likely slightly less of an issue than it would have been a few weeks ago. On the Republican side, there is no doubt the party will nominate Donald Trump for a second presidential term, whilst former Vice President Joe Biden has built up what appears to be an unassailable lead in the race over Senator Bernie Sanders to become the Democratic nominee. That said, party conventions, and the associated mix of high level politics and razzmatazz, are important events in the lead up to presidential elections. Aside from the obvious economic hit to both Charlotte and Milwaukee, if they were to be cancelled, or at least scaled-down, this would be important as it would prevent Biden from making the traditional keynote convention speech, a set-piece event in a presidential election campaign.

“Vote by Mail – 3/21/2020 Portland Lone Fir Cemetery Walk” by Mark McClure is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0

Increase postal voting

The Covid-19 crisis could lead to an increase in voting by mail. This may come by people voluntarily requesting a mail-in ballot or by states instituting mail-in ballots to prevent people congregating at polling stations, or a mixture of the two. Over 20 states allow some elections to be carried out completely by mail ballots. Indeed, Oregon, Washington, Hawaii and Colorado now hold elections entirely by mail (albeit with some capacity for people to vote in person in some of these states). Yet, there would be inherent dangers in ramping up postal voting across a short space of time in a complex system. As Matt Blaze of Georgetown Law School notes, ‘[t]here are 50 states with 50 sets of unique election laws, so everyone has to anticipate how this kind of big change would impact them’. Another option could be to move ballots online. Yet, as the 2016 election demonstrated, there is an inherent danger in relying too heavily on technology in election administration.

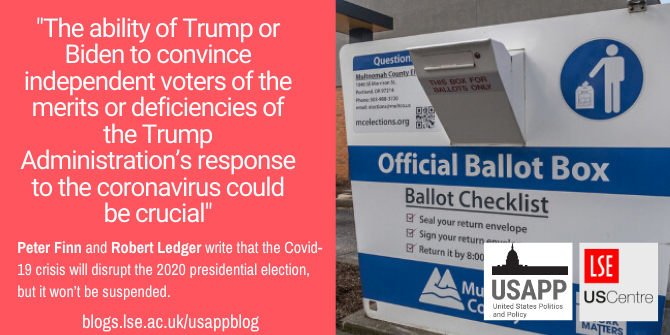

Influence on voting decisions

While it is hard to know how the crisis will evolve, if Trump is continually seen as providing misleading information or having been slow in responding to the crisis it could influence voters come November. However, another outcome is that people continue to view the crisis through the prism of party politics. An NPR/PBS poll released on March 17th showed 83 percent of Democrats disapproving of ‘how President Donald Trump is handling the coronavirus pandemic’, as opposed to just 11 percent of Republicans. Interestingly, the split in independent voters was much more even, with 40 percent saying they approve, 50 percent saying they disapprove and 10 percent unsure. Given how tight a small number of swing states might be in November, the ability of Trump or Biden to convince independent voters of the merits or deficiencies of the Trump Administration’s response to the coronavirus could be crucial.

Disruption to the general election

Perhaps the largest effect that the crisis could have is on the general election, which is scheduled for November 3rd 2020. Yet, while primaries and caucuses are internal political party processes, with precedent existing for moving primaries at various levels, the general election itself is a core constitutional process, with the 20th Amendment of the US Constitution mandating that the ‘terms of the President and the Vice President shall end at noon on the 20th day of January’ following an election. This leaves little logistical room for manoeuvre even if an election was suspended. There has been some discussion of whether Trump may try to suspend the election. However, as numerous commentators have pointed out, it is not in his gift to do so as the date is set via the US Code, which is written by Congress. In terms of precedent, the 1864 presidential election went ahead during the US Civil War. Similarly, 1944 saw Franklin D. Roosevelt win a fourth presidential term. Finally, in 1918 a midterm election took place during that year’s Spanish Flu outbreak. As such, while it is likely the logistics of holding the election may need to be altered, it is, bar a huge and uniquely unprecedented national emergency evolving over the next six months, all but certain the election will occur as scheduled.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3bnFIJW

About the authors

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Dr Peter Finn is a multi-award-winning Senior Lecturer in Politics at Kingston University. His research is focused on conceptualising the ways that the US and the UK attempt to embed impunity for violations of international law into their national security operations. He is also interested in US politics more generally, with a particular focus on presidential power and elections. He has, among other places, been featured in The Guardian, The Conversation, Open Democracy and Critical Military Studies.

Robert Ledger – Schiller University

Robert Ledger – Schiller University

Robert Ledger has a PhD in political science from Queen Mary University of London. He has worked for the European Stability Initiative, a think-tank in Brussels, lectured at several universities in London and currently lives in Frankfurt am Main. He is a Visiting Researcher (Gastwissenshaftler) in the History Seminar at Goethe University and also teaches at Schiller University Heidelberg and the Frankfurt School of Finance & Management. He is the author of Neoliberal Thought and Thatcherism: ‘A Transition From Here to There?’