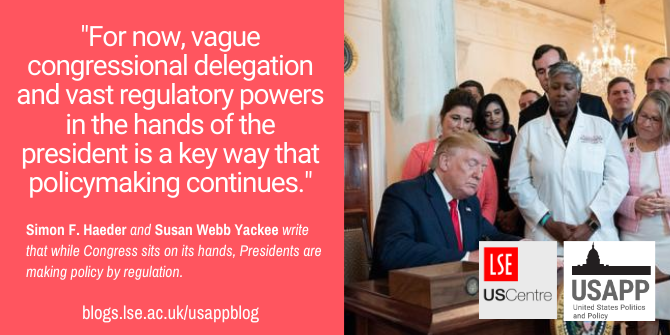

Despite what most of the public may think, the vast majority of policymaking by the federal government comes in the form of rules and regulations rather than through new laws. Using the 2010 Affordable Care Act as a case study, Simon F. Haeder and Susan Webb Yackee write that the move from law-based to regulatory policymaking has given Democratic and Republican presidents alike unprecedented powers that often do not need to take into account the views of Congress.

Despite what most of the public may think, the vast majority of policymaking by the federal government comes in the form of rules and regulations rather than through new laws. Using the 2010 Affordable Care Act as a case study, Simon F. Haeder and Susan Webb Yackee write that the move from law-based to regulatory policymaking has given Democratic and Republican presidents alike unprecedented powers that often do not need to take into account the views of Congress.

In the middle of a global pandemic, the political campaign season is heating up in the United States. In June President Trump held a much-criticized rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the American airwaves are saturated with campaign advertising by both presidential candidates.

Of course, the US House of Representatives and Senate are also up for grabs in the November elections. At this time, predictions put the presidency in the Democratic column, with the House remaining that way, while the (currently GOP-held) Senate appears to be on a knife’s edge with different forecasts putting it in Republican or Democratic hands or, even, a tie. Thus, even if the Democrats were to win the Senate, they would not come close to holding a filibuster-proof majority of 60 in 2021.

So, what does this mean for a potential Democratic President Joe Biden and the Democrats’ ability to shape policymaking after they enter the White House? Would Joe Biden be a lame duck from the very start? Alternatively, should President Trump pull off a victory, what does this mean for his policy ambitions if the Republicans continue with a Congress where at least one house of the legislature is of a different party?

Such questions may produce predictions of policy gridlock. Yet, things might not be as dire as some may think, which we detail in our new work. While major law-based accomplishments might elude a president facing divided government (or lacking a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate), all presidents have one important policy instrument at his/her disposal to shape American public policy: “rulemaking.”

Rulemaking: Policymaking by Administrative Means

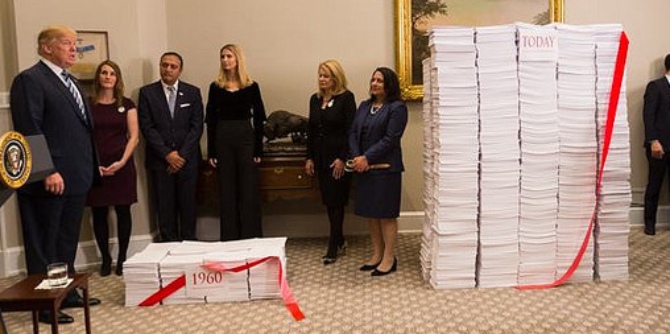

For most casual observers (and many political scientists), American policymaking takes place primarily in the Congress. Yet, a closer look at policy change over the last few decades paints a starkly different picture. Every year, federal government departments and agencies pump out tens of thousands of pages of regulations that carry the weight of law. By one estimate, 9 out of 10 US “policies” are the result of administrative agency actions. This “massive policy output created by public sector administrative agencies” has led some observers of the US policy-making process to conclude that policy making today is primarily administrative rather than legislative. Yet, notably, much this activity occurs outside the public’s and the media’s attention.

Rulemaking as a Presidential Policymaking Tool

While regulation has emerged as the primary form of policymaking in the United States in general, this particularly holds true for the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—President Obama’s signature legislative achievement, which passed in 2010. As we note in our recent article the statutory text of the ACA references the word “secretary” more than 3,000 times to refer to 11 different cabinet agency secretaries. Many if not most of these references are devolving policymaking authority to the government bureaucracy.

‘President Trump Signs an EO on Healthcare Transparency‘ by The White House is Public Domain

While the vast regulatory potential of the ACA is readily apparent in its text, the true reach becomes apparent when looking at the actual regulatory record. By the end of 2019, ACA-derived rulemakings combined for a regulatory policy length of almost 9,000 pages or more than nine million words. This compares to the law’s length of just 961 pages or 474,622 words. As a result, each page in the ACA is matched by more than 9 pages of regulations, while each word in the ACA is matched by more than 19 words in regulations. For those interested, the busiest regulators were the US Departments of Health and Human Services with roughly two-thirds of all rules, and the Departments of Treasury with 17 percent and Labor with 11 percent.

Yet, the extent of ACA rulemaking is only part of the story. We use two case studies to illustrate, the shift from legislative to administrative policymaking has also endowed presidents with significant unilateral powers to shape policies largely without the input from congressional statute writers and, sometimes, in direct opposition to congressional preferences.

Our case studies focus on two hotly contested issues: contraception coverage for women and short-term limited duration insurance plans.

With regards to former, the Obama Administration had sought to walk the tightrope of expanding contraception coverage to most American women while also not offending the millions of Americans that objected to contraception as a result of their religious beliefs. Yet, the issue remained unresolved as the Trump Administration entered office in 2017. Once in office, the new administration abruptly changed course—relying on interim final rules—to provide much more flexibility to employers on religious and moral grounds. This “course correction” has just recently been validated by the US Supreme Court.

Our second case study focused on short-term limited duration insurance plans. Seeking to avoid adverse selection and offer stability to the nascent Affordable Care Act insurance marketplaces, the Obama Administration strictly curtailed the availability of these types of plans. Once again, the Trump Administration reversed course and made these plans much more available. In doing so, the Trump Administration fundamentally changed the orientation of the underlying public policy. As with the contraception issue, the Trump Administration found support for their actions in front of the courts.

Implications for US Policymaking

While we have focused on the Affordable Care Act, opportunities for presidential policymaking via regulations inherently emerge from almost every statute Congress passes. And for good reason. Congress does not have the expertise or resources to hash out all policy details in legislative statutes. Indeed, specificity would also make compromise and bill passage much more challenging, if not impossible, because much of the ambiguity needed to bring congressional lawmakers on board would be eliminated.

In a time of congressional gridlock, many would say that the ability to move policy along is crucial to keep the country functioning. For now, vague congressional delegation and vast regulatory powers in the hands of the president is a key way that policymaking continues. But policymaking via rulemaking also has its drawbacks. As we highlight, two different presidential administrations can propose—and deliver—two diametrically opposed ways to implement the same congressional statute. As a result, the Affordable Care Act’s regulatory implementation over the last decade provides a cautionary tale regarding the role that congressional delegation plays within the US policymaking process.

- This article is based on the paper ‘A Look Under the Hood: Regulatory Policy Making and the Affordable Care Act’ in the Journal of Health Policy, Politics and Law.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3jMjNB1

About the authors

Simon F. Haeder – Pennsylvania State University

Simon F. Haeder – Pennsylvania State University

Simon F. Haeder is an assistant professor in the School of Public Policy at Pennsylvania State University. He also is a fellow in the Interdisciplinary Research Leaders (IRL) program, a national leadership development program supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. He also was part of the inaugural cohort of the American Enterprise Institute’s Emerging Poverty Scholars program. sfh5482@psu.edu

Susan Webb Yackee – University of Wisconsin–Madison

Susan Webb Yackee – University of Wisconsin–Madison

Susan Webb Yackee is the Collins-Bascom Professor of public affairs and political science and is director of the La Follette School of Public Affairs at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Her research interests include the US public policy-making process, public management, regulation, and interest-group politics. She received the 2019 Herbert A. Simon Career Award from the Midwest Public Administration Caucus.