Historically in times of crisis, presidents experience a polling boost as Americans ‘rally around the flag’, but this has not been the case during President Trump’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. In new analysis, Harold Clarke, Marianne Stewart and Paul Whiteley find that the massive partisan and ideological differences in the electorate meant that the expected spike in Trump’s support did not occur – especially among the most vulnerable, who would ordinarily be more likely to rally around the president.

Historically in times of crisis, presidents experience a polling boost as Americans ‘rally around the flag’, but this has not been the case during President Trump’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. In new analysis, Harold Clarke, Marianne Stewart and Paul Whiteley find that the massive partisan and ideological differences in the electorate meant that the expected spike in Trump’s support did not occur – especially among the most vulnerable, who would ordinarily be more likely to rally around the president.

Voters’ judgments about how President Trump has handled the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic likely will be an important factor in the fast-approaching presidential election. Historically, public opinion polls display a strong tendency for people to rally in support of the president in times of major crises. The beginning of the Iranian hostage crisis in November 1979, Operation Desert Storm in January 1991 and the 9/11 terrorist attacks in September 2001 are well known examples of major events that stimulated large surges in presidential approval. The effects of COVID-19 are quite different.

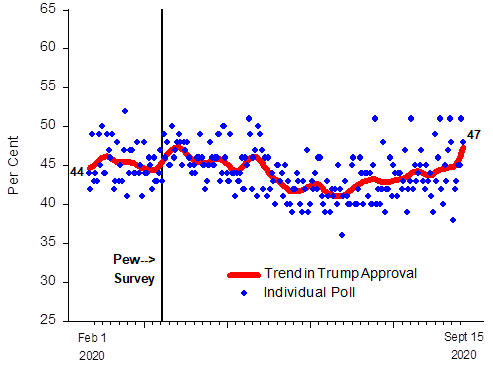

As Figure 1 illustrates, opinion polls conducted since February of this year do not show an upward spike in President Trump’s ratings accompanied the virus’ outbreak. Rather, the trend in his approval ratings continued to vary across a narrow range in the mid to low 40s, much as it has throughout his term in office.

Figure 1 – Trend in Trump Job Performance Approval, February 1st – September 21, 2020

Source: Real Clear Politics.

A large representative national survey of over 11,500, conducted by the Pew Foundation in March helps us to understand why. When asked about Trump’s handling of the Corona virus outbreak, slightly less than half (49 percent) of those surveyed said he had done a good or an excellent job. In sharp contrast, nearly three-quarters gave positive ratings to state and local elected officials and four-fifths approved the efforts of public health officials.

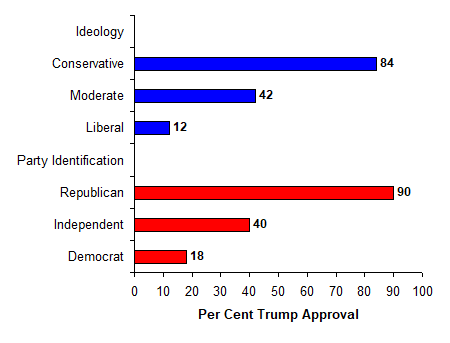

There were massive partisan and ideological differences in assessments of the President’s Covid response. Figure 2 shows that fully 90 percent of Republican supporters approved of Trump’s handling of the virus as compared to only 18 percent of Democrats. Similarly, 84 percent of self-identified conservatives but only 12 percent of liberals approved. Trump’s decidedly mediocre COVID-19 performance ratings across the entire electorate has concealed very different appraisals by opposing partisan and ideological camps.

Figure 2 – Approval of Trump’s Handling COVID-19 by Partisanship and Ideology

Source: March 2020 Pew Foundation Survey.

Although important, partisanship and ideology are not the only story. When the Pew study was conducted, not everyone accepted the idea that the virus outbreak signaled the onset of a significant crisis. One-third of the survey respondents rejected that characterization and designated it as a ‘serious’ or even a ‘minor’ problem. Moreover, those identifying the virus as a crisis were considerably less (not more) likely than other people (42 percent versus 61 percent) to approve of Trump’s handling of the situation. The Pew data thus testify that overall the incipient pandemic did not influence public opinion the way previous research on the dynamics of presidential approval in crisis situations would suggest.

The idea that a rally in favor of the president was overwhelmed by the deep partisan and ideological polarization that characterizes American politics is certainly plausible. However, other data on the health impacts of the pandemic caution that this conclusion is not sufficiently nuanced. State-level analyses that we conducted in the late spring indicate that controlling for factors such as population size and density, education, income and the capacity of state health care systems, minorities and other disadvantaged groups were significantly at greater risk than other people of contracting and the virus and dying from it.

This finding suggests that members of vulnerable groups in the population may have reacted differently to the onrushing pandemic than did people in more advantaged groups. ‘Vulnerables’ may have been prone to rally to the president while more advantaged people who judged COVID-19 as a crisis interpreted it as evidence that Trump was not doing an adequate job of combating the growing threat.

“Photo by Charles Deluvio on Unsplash“

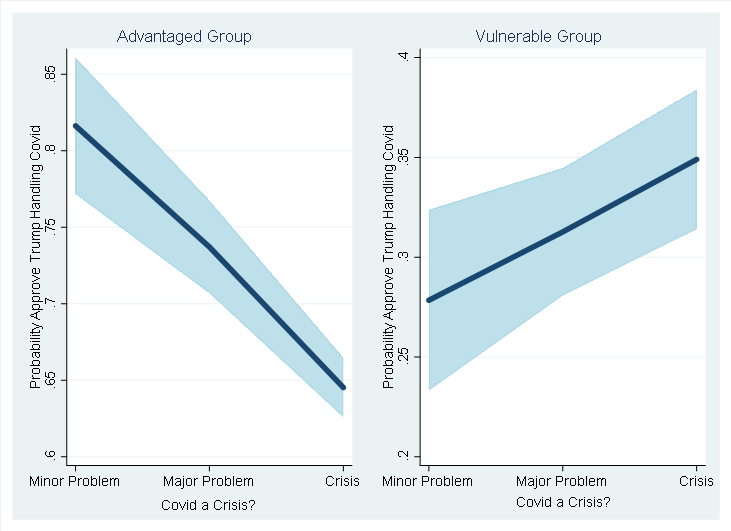

Analyses of the Pew survey data using what statisticians call a ‘finite mixture model’ support this idea. This allows us to separate out different groups or ‘latent classes’ and examine their attitudes to the crisis and see what they think about presidential performance. Controlling for partisanship, ideology and several other factors, the analyses indicate the impact of crisis perceptions on judgments about the president’s handling of COVID-19 were quite different across two groups in the electorate. The first group can be described as ‘advantaged’ because they are generally financially better off, better educated, and more likely to be male and white than the whole population. The second group or the ‘vulnerable’, have the opposite characteristics. As Figure 3 shows, for otherwise average individuals in the first ‘advantaged’ group, perceptions that COVID-19 is a serious crisis were associated with lower levels of presidential approval, whereas for the second ‘vulnerable’ group such perceptions were associated with higher levels of approval. Both latent classes were sizable—56 percent are estimated to be in the advantaged group and 44 percent in the vulnerable group.

Figure 3 – Probability of Approving President Trump’s Handling of COVID-19 by Perceptions of Seriousness of the Situation

Note: results of binomial logit finite mixture model of factors affecting judgments about Trump’s handling of COVID-19

If a large majority of people viewed the rapidly spreading virus as a crisis and many of them were predisposed to rally to the president, then why did Trump’s approval ratings not register a sizable uptick in the polls? Figure 3 suggests the answer. The usual ‘rally round the president’ effect in a crisis was reversed for the ‘advantaged’ group and so it cancelled out the positive effect in the ‘vulnerable’ group. However, as Figure 3 also shows, among the ‘vulnerable’ group the probability of approving the president’s handling of the situation remained quite low—only .34 on a 0 to 1 scale. In other words, the positive rally effect in the vulnerable group was too weak to do much to boost the president’s poll numbers.

This finding accords well with the familiar observation that many members of ethnic/racial minority communities and large numbers of women and lower income Americans identify with the Democratic Party and consider themselves to be to the left-of-center politically. And, as Figure 2 testifies, very few Democrats or liberals evaluated the president’s handling of the onrushing pandemic positively.

In sum, the deep partisan and ideological fissures in American public opinion swamped tendencies among those who were especially vulnerable to rally around the president as the COVID-19 crisis was unfolding. Several months later, the health and economic threats posed by the pandemic continue to affect people in these vulnerable groups disproportionately, and President Trump has repeatedly proclaimed that he has mobilized the medical and scientific communities to work at ‘warp speed’ to develop an effective vaccine. When and whether that will happen remain unknown, but the probability that partisanship and ideology will continue to ‘trump’ vulnerability when voters make electorally consequential judgments about the president’s handling of the pandemic and other important issues remains high.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/33FC0u7

About the authors

Harold Clarke – University of Texas at Dallas

Harold Clarke – University of Texas at Dallas

Harold D. Clarke, Ph.D. Duke University is Ashbel Smith Professor, School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas, and Adjunct Professor, Department of Government, University of Essex.

Marianne Stewart – University of Texas at Dallas

Marianne Stewart – University of Texas at Dallas

Marianne Stewart is Professor of Political Science in the School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences at the University of Texas at Dallas.

Paul Whiteley – University of Essex

Paul Whiteley – University of Essex

Paul Whiteley is a Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Essex. His research interests are in electoral behaviour, public opinion, political economy and political methodology.