Tourism has taken an enormous hit during the pandemic. Simeon Djankov looks at some of the ways governments are trying to revive the sector – from holiday vouchers to socially distanced group tours.

Tourism has taken an enormous hit during the pandemic. Simeon Djankov looks at some of the ways governments are trying to revive the sector – from holiday vouchers to socially distanced group tours.

For years, residents of Barcelona, Paris and Venice and resorts like Martha’s Vineyard, Santorini and Ibiza have complained about the millions of tourists who visit them each year. In 2020, they got a reprieve, but not the sort they bargained for.

Across advanced economies, tourism has collapsed to between a quarter and a third of its 2019 level. Some types of tourism – for example business travel and conventions – have disappeared altogether.

A survey of businesses in the tourism sector in OECD countries finds that more than half may not survive until 2021. The main reason for this dire forecast is the prevalence of small businesses operating in tourism – family hotels, restaurants, travel agencies and entertainment venues.

How the tourist sector has already changed

In 2019, tourism made up 10 percent of global GDP, worth $9.3 trillion. In several European countries, its share is significantly higher. For example, tourism in Croatia contributes 24% of GDP, in Greece 20%, in Spain 12%, in Portugal 8%, and in France 7.5%. In the United States, tourism generated $1.5 trillion, or 4.7% of GDP.

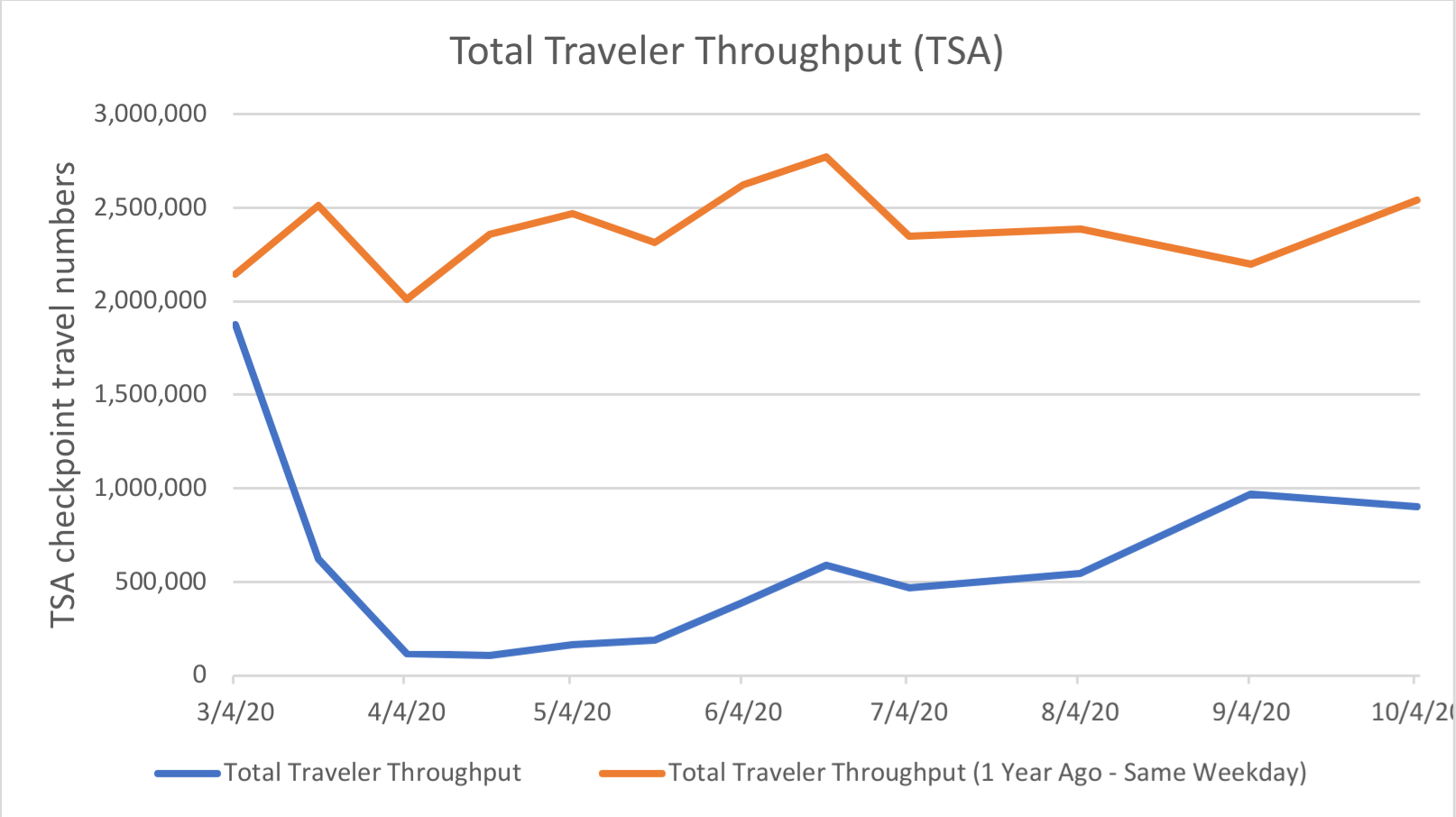

But not in 2020. Travel bookings in the US are at about a third of last October’s (Figure 1). In September, two out of three hotels were below one-third occupancy, according to an industry study, and four out of 10 hospitality workers remain unemployed. Greece reached 35 percent occupancy in the late summer, with many luxury hotels remaining closed altogether. This mark still exceeds the occupancy rate in Portugal (around 25 percent) and Spain (around 30 percent). Winter leisure tourism is problematic too, as the opportunity for social distancing at ski resorts and on cruises is limited.

Figure 1 – Traveller throughput at US airports, 2019-2020

Apart from summer and winter holidaymakers, tourism traditionally depends on business travel. The pandemic has changed this pattern too. The expectation in the tourism sector is that many firms will discover that they can conduct work efficiently on a remote basis and will come to see business travel as an unnecessary expense. Conferences and other business-oriented conventions may likewise be a thing of the past.

What can be done to resuscitate tourism?

Governments in OECD countries have so far come up with five measures to alleviate the collapse in tourism flows.

Injecting liquidity into tourism businesses

Latvia has introduced a reduced value added tax rate of 5% for catering and tourist accommodation sectors. So have France, Greece, and Germany. In Switzerland, a legal standstill for the tourist industry was put in place regarding customer claims arising from the default of a travel service. A third of OECD countries, starting with Greece and Italy, have introduced dedicated lines of credit for tourism businesses through state-owned development banks. These lines of credit have long grace periods (up to five years), providing liquidity without additional interest-payment burden on companies.

Boosting local demand for tourism through voucher schemes

The origin of this idea was the “Eat Out to Help Out” discount scheme in the UK, which applied to eat-in food and drink on Monday to Wednesdays. The discount is capped at £10 per person and does not apply to alcohol. France is providing consumers with restaurant discounts of EUR 38 each. These discounts can be used on weekends and holidays to allow visitors to spend in bars and restaurants. Italy’s recovery programme allots every family free vouchers for cinema, theatre, museum and concert-going. Italy is also refunding 10% on credit card transactions, up to EUR300, for foreign and local tourists alike.

Creating holiday subsidy programmes for domestic tourists

Some governments are encouraging local tourism spending by introducing holiday subsidy programmes. South Korea, for example, provides workers with bonuses equivalent to 25% of the cost of the holiday. Southern European countries have variations of such holiday subsidy schemes, as do other European countries like Germany and Sweden. Japan goes a step further, covering hotel costs for the first three days of a week-long holiday.

Investing in digital solutions to replace human contact in the tourist industry

France and Germany are subsidising rental car companies to update their fleets with electric cars – part of a broader green recovery initiative. Government money also funds the development of online apps for booking tourist services and producing online tourist guides.

Reshaping group leisure travel

Group travel brings in significant revenues in large cities like Vienna and Amsterdam, mainly from Asian tourists or groups of European retirees. Austria and the Netherlands are financing ways to reshape it, which implies socially-distanced arrangements – for example trains, not buses – and a focus on non-urban sites like parks and historical monuments in the open. This reshaping may take years to mature, and may demand a new type of tourist.

- This article appeared originally at the LSE’s COVID-19 blog.