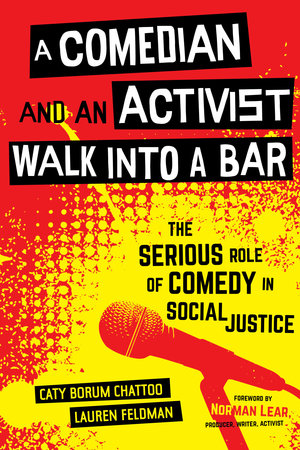

In A Comedian and an Activist Walk into a Bar: The Serious Role of Comedy in Social Justice, Caty Borum Chattoo and Lauren Feldman explore how comedy can serve to advance a social justice agenda. Drawing on her own experience of writing and producing comedy shows in Berlin, Christine Sweeney finds that this book offers answers to questions she has long been pondering: how do we open up social research and discourse to wider audiences; how do we highlight the absurdities of our world, making us laugh and think?

A Comedian and an Activist Walk into a Bar: The Serious Role of Comedy in Social Justice. Caty Borum Chattoo and Lauren Feldman. University of California Press. 2020.

‘If you’re thinking, you’re not laughing. Rule one of comedy,’ my stand-up teacher continued, ‘plenty of political comedians are skilled at this kind of humour, leave political or issue humour to them’. But if I wasn’t allowed to use politics and current events as comedy material, what would that leave? Stale observations about Tinder dates, eccentric people on the bus and worn-out gendered stereotypes? What is the dreadful state of current events if not prime material for comedy?

‘If you’re thinking, you’re not laughing. Rule one of comedy,’ my stand-up teacher continued, ‘plenty of political comedians are skilled at this kind of humour, leave political or issue humour to them’. But if I wasn’t allowed to use politics and current events as comedy material, what would that leave? Stale observations about Tinder dates, eccentric people on the bus and worn-out gendered stereotypes? What is the dreadful state of current events if not prime material for comedy?

That’s right: I went from earning a master’s degree at LSE to a stand-up comedy class. I’ve also taken classes in improv, sketch-writing and sketch producing. How does someone go from a career in policy analysis to full-on immersion in the Frankfurt School of critical theory to chasing English-language open-mic nights in Berlin? For me, comedy was a coping mechanism I’d developed over the past few years of particular political uncertainty. Making jokes of everything was a salve for the sting of total disillusionment. It was an antidote to the earnest and material worlds of economics and politics, which I had come to regard with total cynicism and hopelessness. Once professionally driven to ‘make the world a better place’, the unexpected results of elections and referendums shattered my (naive and overly optimistic) world. I turned away from analysing and solving problems I felt were unsolvable.

With the state of the world, I might offer a revision to my stand-up teacher’s advice on political comedy: ‘If you’re thinking, you’re crying, not laughing.’ From a place of relative privilege, I wanted to stop crying when I thought about global problems of inequality and climate change. Laughing seemed to be the only alternative. However, I felt frustrated with a constructed dichotomy of the silly and serious when, more often than not, I found myself laughing and crying at the same cycle of news. In avoiding actually doing something about it, did I really have to choose between laughing and crying?

And we are more comfortable in knowing or being directed towards when we are meant to be silly versus sombre. Everyone knows the uncomfortable feeling of reacting to a joke that wasn’t intended to be a joke, or taking something seriously that was said in jest. Being able to manipulate people’s reactions with storytelling and context is a power I first witnessed seeing Hannah Gadsby’s stand-up special Nanette. In it, she points out the heartbreaking real-life experiences of violence, poverty and homophobia that inspired her comedy. She has her live audience laughing before uncomfortably pausing when she explains the punchlines of her previous comedy sets. It’s an emotional rollercoaster that she manoeuvres using a dry tone and comedic timing, skills she honed during her previous career as an art history scholar. Her audience came for the comedy, but perhaps left with a deeper understanding of everyday homophobia and the male gaze in classical art.

How does a former academic learn to make others laugh? They research. And nothing makes a joke funnier than explaining it. In A Comedian and an Activist Walk into a Bar: The Serious Role of Comedy in Social Justice, co-authors Caty Borum Chattoo and Lauren Feldman do just that: they explain the joke. Or rather, they explain how comedy can serve to advance a social justice agenda. Perhaps Borum Chattoo and Feldman would argue that activism and comedy are each made better when they collaborate. With overlapping backgrounds in communication scholarship, media strategy in the context of social change and justice, comedy and creative media production, the authors bring a veritable Venn diagram of perspectives. The central argument is that ‘comedy’s potential for public influence in the context of social issues is newly powerful in the digital media age’. They suggest that comedy isn’t a tool for social justice strategic communications, but rather an artform to depict what public radio would call ‘the world’s most pressing issues’.

The book examines how different forms of mediated comedy, including satirical news, scripted episodic TV, comedy documentary, stand-up comedy and sketch, have the unique potential to increase message and issue attention, disarm audiences, lower resistance to persuasion, break down social barriers and stimulate sharing and discussion. If this sounds like a practical handbook for communication strategists more than an academic discourse analysis, you’d be partially correct. As someone who is professionally indecisive and curious to a fault, I’ve spent time in academia, social justice and comedy. My brain is constantly making jokes, and then overanalysing those jokes to a point where I am a bit too silly for academia and a bit too serious for comedy; this book quite eerily spoke to me.

A Comedian and an Activist Walk into a Bar doesn’t argue for or against comedy as a vehicle for social justice. Rather, it lays out how convergence culture, the power of the media consumer to influence the media producer, has allowed for ‘niche’ comedy, from comedians previously regarded as ‘niche’, to use identity or format to send a message via a larger platform, thanks to technology. Whereas mediated comedy used to be censored by mass-market demands, ratings and the tastes of executive gatekeepers, streaming has expanded and diversified platforms for emerging voices.

In a world where news and entertainment are interspersed on news feeds, and ‘news’ takes on a double-meaning of current public and private events, ‘The News’ has expanded to cover more frivolous topics, like gossip and the personal lives of public figures. At the same time, entertainment has taken on more serious topics. The internet’s globalisation of both news and entertainment has also expanded access to diverse commentary on this content. An optimistic reading of technology’s power to connect us would suggest that it also has the power to build empathy, giving us access to the experiences and perspectives of others. According to Borum Chattoo and Feldman, comedy, sharing a joke, requires that comedians and audiences have a common understanding of current affairs, in order to then distort that reality. Global access to news media expands our shared library of comedic ‘material’. Those who deliver that comedy can describe the absurdity they experience every day. To quote fictional comedienne Miriam ‘Midge’ Maisel, otherwise known as The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel:

Comedy is fueled by oppression, by the lack of power, by sadness and disappointment, by abandonment and humiliation. Now, who the hell does that describe more than women? Judging by those standards, only women should be funny.

If oppression, lack of power, sadness and disappointment are the stuff of great comedy, perhaps we are in a Golden Age of humour. The mechanics of turning this dark matter into something that is at once funny and thought-provoking is another major theme of the book. Borum Chattoo and Feldman describe the ways in which satirical comedians like Jon Stewart, John Oliver and Samantha Bee effectively break down complex concepts, particularly in US and global politics, for issue awareness and social change. For example, ahead of the 2012 US presidential elections, Stephen Colbert made campaign finance law understandable, describing how money is effectively laundered to legally fund candidates. While his audience may not had gone out of their way to study complex campaign finance law, on his show comedy served as a primer to get people to pay attention. This is the role of comedy in social justice. Getting us to pay attention.

From a social science research perspective, Borum Chattoo and Feldman sprinkle in studies demonstrating comedy’s ability to promote information retention. In another, 20 minutes of stand-up comedy was comparable to 20 minutes of exercise in terms of promoting positive wellbeing. Other studies show the ways in which comedy induces ‘arousal and mirth’, disarming us and making us more playful. This openness helps us to see the world in new ways.

While satirical news shows like Trevor Noah’s The Daily Show and Oliver’s Last Week Tonight often preach to a progressive choir, scripted episodic television has the power to introduce social issues and diverse viewpoints to wider audiences. Borum Chattoo and Feldman give the example of Black-ish, a US family sitcom created by Kenya Barris. With Nielsen data suggesting that as many as 80 per cent of the show’s viewers since the 2016-17 season are not Black (62), the show has brought themes of racism and police brutality to those who may not have had personal experience of or previous engagement with these topics. Scripted television, particularly in the US, has served as a ‘centralised system of storytelling that shapes perceived social reality of its audiences’, or cultivation theory. Through this centralised storytelling, contact hypothesis suggests that ‘positive interactions between members of diverse social groups can reduce prejudice, providing opportunity to learn more about other groups’. In other words, scripted television has the power to build familiarity with those seemingly unfamiliar to us in our everyday lives, meeting viewers where they are in their understanding of cultural, gender and race issues.

A Comedian and an Activist Walk into a Bar analyses other comedic forms like stand-up and sketch, which offer more intimate and agile modes of social commentary. Comedians can use deeply personal narratives to illuminate social justice issues, reframing the experiences of marginalised groups. Sketch comedy from shows like Saturday Night Live can more nimbly tackle news cycles with short-form parodies of current events.

Borum Chattoo and Feldman helpfully use specific global issues like climate change, poverty and inequality as examples of how comedy can bring people together to understand and care about the kind of topics that leave us feeling overwhelmed and helpless. When conventional news reporting shows the bleak realities of global warming and growing wealth inequality, comedy offers a way through fatigue and despair while staying engaged. Borum Chattoo and Feldman note that while environmentalists and humanitarians have long been doing the hard work of activism, they can be seen as didactic and aggressive.

Mediated ‘poverty porn’, images of starving children first featured in 1980s telethons to raise money for charities, has further fatigued audiences. These mediated narratives of poverty, while originally intended to build empathy, have reinforced damaging economic archetypes. A 2017 United Nations report on US poverty cited ‘caricatured narratives’ of poverty in the public mind, portraying the wealthy as moral and hardworking, and the poor as lazy and backward. Comedy has the power to challenge these narratives, skewering the status quo and the absurdities of systems that reinforce inequality. Crucial to social justice comedy’s ability to reframe narratives is punching up, rather than punching down: creating spaces for those who have experienced poverty to tell their own stories. In many cases, promoting storytelling involves expanding the comedy stage for comedians who have experienced poverty.

Among the most relatable chapters of Borum Chattoo and Feldman’s book are those focused on comedians’ perspectives as accidental or intentional social activists. Comedians like Hasan Minhaj (Netflix’s Patriot Act), Francesca Ramsey (MTV’s Decoded) and Issa Rae (HBO’s Insecure) share how, as members of marginalised communities in the US, they struggled to access the traditional stand-up club circuits, and instead got their start on platforms like YouTube.

While club circuits of the past have rewarded ‘lowest common denominator’ humour that speaks to mainstream (traditionally white, cisgender, heterosexual male) audiences, social media removed traditional gatekeepers, connecting audiences with comedians who reflected their own experiences. For many of these comedians, their lived experiences, real stories of discrimination and abuse, serve as their material in ways that can highlight the absurdity of racism and sexism embedded in mainstream culture. These comedians use humour to build empathy, illuminate, demystify, mock power, instruct, educate, humanise and represent. When your everyday experience of racism and sexism has not been previously represented, it becomes topical and imbued with social justice, whether intentional or not.

But what about when non-comedians seek to use humour to advance social justice agendas or when media executives and entertainers seek research and expertise to strengthen social justice comedy? Borum Chattoo and Feldman use interviews with emerging social justice communication firms and studio executives to suggest how activists and comedians can more effectively collaborate, making what is funny more informed, and what is informational more funny. They describe a careful balance of social activism groups serving as an information resource for entertainment, while respecting comedians as artists with creative licence. Too much information can outweigh comedy, while too little can trivialise serious topics.

Who is A Comedian and an Activist Walk into a Bar written for? The vagueness of the intended audience is both a strength and weakness of the book, further illustrating the oppositional forces of serious academic analysis that cause us to sit up straight and pay attention, and the comedy that disarms us and makes us laugh. The book offers answers to many of the questions I’ve had since grad school: how do we open up social research and discourse to wider audiences; how do we highlight the absurdities of our world, making us laugh and think? Comedy that does this well doesn’t make light of serious issues; it sheds light on them (sorry!). Bringing together researchers, activists and comedians can only serve to support more informed, engaged and hopeful audiences.

- This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

- Banner Image Credit: Photo by Matthias Wagner on Unsplash., In-Text Image 1 Credit: Photo by Robinson Recalde on Unsplash., In-Text Image 2 Credit: Photo by tanialee gonzalez on Unsplash.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2T1FmRX

About the reviewer

Christine Sweeney

Christine Sweeney writes and produces comedy shows in Berlin. Before that, she researched gender representation in media and earned an MSc in Media and Communications at LSE. Before that, she worked in international development and tech policy.