Over the past decade many US cities have attempted to fix budgetary holes by raising revenues via enforcing their municipal codes. Dick M. Carpenter II investigates three cities in Georgia which undertake “taxation by citation”. He finds that the budget share of fines and fees were three times higher for these cities than in others, most citations had little to do with public safety, and local courts also play an important part in revenue generation.

Over the past decade many US cities have attempted to fix budgetary holes by raising revenues via enforcing their municipal codes. Dick M. Carpenter II investigates three cities in Georgia which undertake “taxation by citation”. He finds that the budget share of fines and fees were three times higher for these cities than in others, most citations had little to do with public safety, and local courts also play an important part in revenue generation.

In August 2014, the city of Ferguson, Missouri, came to international attention when a police officer shot and killed Michael Brown, and the city erupted into protests. Many observers blamed systemic racism for the unrest. Yet a 2015 US Department of Justice report found another, more mundane factor was also at work: city code enforcement.

For many years preceding Brown’s killing, the city uncompromisingly enforced its codes to raise revenue. City leaders pressed the politically appointed police chief and municipal court judge to help meet growing budget pressures through citation – a ticket or notice stating a law violation – revenue. The practice created long-smoldering tensions between law enforcement and citizens—more than two-thirds of whom are black. Brown’s killing ignited the tensions into three waves of dayslong protests.

Although it might be tempting to dismiss Ferguson’s pursuit of citation revenue as anomalous, the municipality placed a mere 18th on a list of US cities in such activity. Cities across the country—in Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Missouri, New York State, Tennessee, and Utah—ranked above Ferguson. And, as evidenced by a 2017 US Commission on Civil Rights report, concern is growing that it may be more common than previously recognized for cities to use code enforcement to fill municipal coffers rather than solely to protect the public. Critics have dubbed such activity “taxation by citation.”

How some cities rely on fines and fees

Despite these concerns and with only a few exceptions like Ferguson, little is known about the types of municipalities that generate substantial revenues through fines and fees. What is the profile of such cities? What processes and structures do they use to generate revenue? To what extent is health and safety served by this practice?

To begin to answer these questions, my co-authors and I completed case studies of three Georgia cities that have historically relied on fines and fees as an important revenue source: Clarkston, Morrow, and Riverdale. In addition to being modest in size and located in the Atlanta area, the cities are home to large percentages of low-income residents and racial/ethnic minorities. And, in 2012, they produced between 18.7 and 24.4 percent of their revenue from fines and fees, putting them among the top 10 US cities for such revenue generation.

Our analysis relied on extensive data collection—city and state financial documents, court observations, census data, videos and photos of city neighborhoods and traffic, court caseloads, code enforcement records, city council meeting minutes, and probation data.

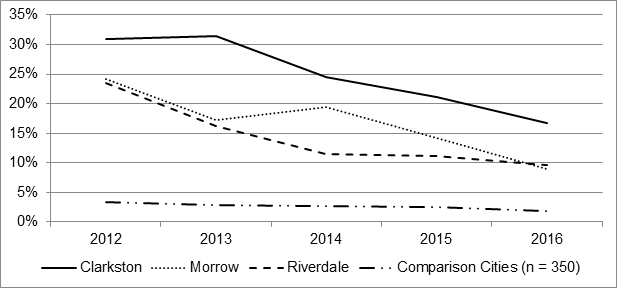

Our primary findings were three-fold. First, fines and fees consistently represented the second largest revenue source, after property taxes, for the sample cities. From 2012 to 2016, fines and fees accounted for annual average revenue shares of 14 percent for Riverdale, 17 percent for Morrow, and 25 percent for Clarkston. Taxes represented between 58 and 71 percent of revenues. In comparably sized Georgia cities, fines and fees accounted for only three percent of revenues. Figure 1 presents annual fines and fees percentages spanning 2012 to 2016. The decreasing trend likely represents a diminishing reliance on fines and fees as the post-recession economy improved. This is precisely the explanation offered by Morrow’s former mayor. When asked why fines and fees revenue appeared to be declining, he responded, “Current trends and forecasts do show improvement, and our city does not have the same crisis situation to face during the next budget year.”

Figure 1 – Fines and Fees as a Share of Revenues Over Time, Fiscal Years 2012–2016

Second, the sample cities generated fines and fees revenues by issuing large numbers of traffic and non-traffic citations for violations that rarely threatened public health and safety. Among traffic tickets, non-speeding violations represented the greatest proportion. These included parking and lane violations, window tinting, illegal U-turns, and expired tags. Non-traffic citations were those issued for misdemeanor personal conduct, such as loitering in a park after hours or noise violations, or aesthetic property violations, such as debris accumulation, tall grass and weeds, or a failure to maintain cleanliness or neighborhood standards.

Third, municipal courts appear to play a central role in revenue generation. Courts should act as neutral referees between city prosecutors and defendants. But based on archived data and our own observations, we question whether the sample cities’ courts live up to that ideal. In practice, their procedures suggest revenue generation may be a major goal; all the courts operate as well-oiled machines.

During our courtroom observations, proceedings moved quickly, with many cases covered in each session. On average, each case was processed in two to three minutes. Data show the sample cities cleared—that is, disposed of—more cases than comparison cities (see Figure 2). The latter cleared about half their caseloads. In the sample cities, clearance rates were between 7 and 33 percentage points higher, on average. Perhaps most tellingly, sample city defendants—few of whom had legal representation—pleaded or were found guilty in 97 percent of cases, on average.

Figure 2 – Court Cases Processed, 2012–2016

Ability-to-pay determinations were conspicuously inconsistent—observed in 59 percent of cases across all three cities. When judges made these determinations and found defendants unable to pay fines, they sentenced most to probation. Judges rarely assigned alternative sentences, such as community service. While probation affords defendants time to pay fines, that benefit can become a liability as fees accrue during the probation term.

“Ticket” (CC BY 2.0) by chucknado

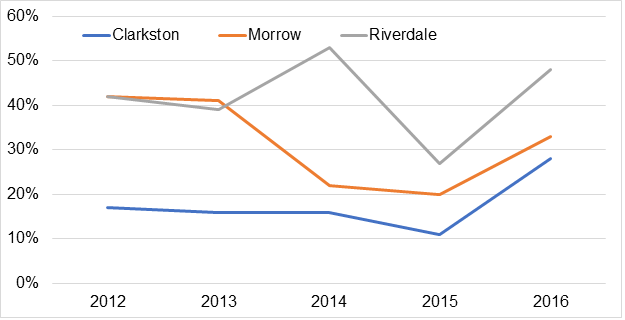

Clarkston and Morrow consistently assigned more than twice as many people to probation as statewide averages, and those probations were processed by private, for-profit companies. Riverdale assigned even more people to probation, although it ran its own probation services. Its probation population was more than seven times the statewide average. For all three cities, probation produced more than $9 million in fines from 2012 through 2016, representing an average of 17 to 42 percent of total fines revenue. Figure 3 illustrates the annual percentages by city.

Figure 3 – Percentages of Total Fines Revenue Collected Through Probation, Fiscal Years 2012–2016

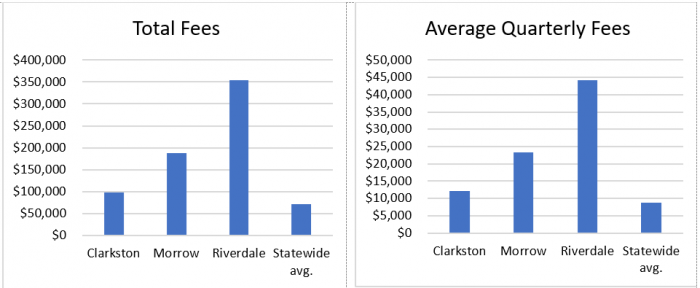

Added to that was more than $600,000 in probation-related fees in 2016 and 2017 for all three cities. The left panel in Figure 4 illustrates the total fees taken by each of the sample cities compared to the statewide average. As shown in the right panel, the cities’ quarterly averages outpaced those statewide, with Riverdale’s being almost five times greater than statewide averages.

Added to that was more than $600,000 in probation-related fees in 2016 and 2017 for all three cities. The left panel in Figure 4 illustrates the total fees taken by each of the sample cities compared to the statewide average. As shown in the right panel, the cities’ quarterly averages outpaced those statewide, with Riverdale’s being almost five times greater than statewide averages.

Figure 4 – Fees Collected Through Probation, 2016–2017

Overall, the sample cities share several important characteristics: They are poorer than average, face uncertain economic futures, and appear to have few means of generating substantial revenues. They process citations through their own courts, which rely on municipal revenue to fund their operations and whose judges are political appointees.

This all suggests systemic incentives may produce taxation by citation, which can put government revenue above individual rights. Cities should use code enforcement only to protect the public—and only with meaningful safeguards for citizens’ rights in place. A few local governments have already begun to adopt needed reforms. The Fines and Fees Justice Center can help municipalities develop customized solutions with community input. Recent reforms in San Francisco, Chicago, and New York have included making fines fairer, eliminating unnecessary fees, reducing fees for low-income residents, creating payment plans, implementing ability-to-pay determinations, and ending driver’s license suspensions for people who cannot pay fines. Such efforts are a good start; cities of all sizes across the United States should follow suit.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘A Case Study of Municipal Taxation by Citation’, in Criminal Justice Policy Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3etBzrN

About the author

Dick M. Carpenter II – University of Colorado

Dick M. Carpenter II – University of Colorado

Dick M. Carpenter II is a professor at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs and a senior director of strategic research at the Institute for Justice.