Once seen as the archetypal swing state, Ohio has voted for the Republican candidate in the last two presidential elections. Kevin Fahey takes a deep dive into the changing electoral fortunes of the Democratic Party in The Buckeye State, writing that while the party tends to perform well in urban areas in many other Midwestern states, this is not the case in Ohio where the party faces significant vote deficits among suburban and rural voters.

Once seen as the archetypal swing state, Ohio has voted for the Republican candidate in the last two presidential elections. Kevin Fahey takes a deep dive into the changing electoral fortunes of the Democratic Party in The Buckeye State, writing that while the party tends to perform well in urban areas in many other Midwestern states, this is not the case in Ohio where the party faces significant vote deficits among suburban and rural voters.

- Following the 2020 US General Election, our mini-series, ‘What Happened?’, explores aspects of elections at the presidential, Senate, House of Representative and state levels, and also reflects on what the election results will mean for US politics moving forward. If you are interested in contributing, please contact Rob Ledger (ledger@em.uni-frankfurt.de) or Peter Finn (finn@kingston.ac.uk).

Ohio used to matter – a lot – in presidential elections. In the 2004 election, Ohio was the most-contested state. Presidential candidates George W. Bush and John Kerry visited the state 41 times and invested tens of millions of dollars in winning the state’s 20 electoral votes. In 2008, Barack Obama and John McCain visited the state 50 times and spent almost $50 million in advertising. Yet this era as a perennial swing state is gone: despite narrowly voting for winning candidates from 1992 to 2012, The Buckeye State gave Donald Trump an 8-point win in both 2016 and 2020. Has Ohio abandoned its swing-state status?

There is ample reason to suspect this is the case. First, the Democratic coalition that even as recently as 2012 propelled Obama’s re-election victory has changed, not just in Ohio but around the country. As a consequence, this new coalition has proven much less competitive in Ohio. Second, Ohio’s own changing demographics suggest that Democrats cannot rely on a “base-first” electoral strategy; to win back the state in 2024, Joe Biden will need to appeal to two-time Donald Trump voters. Yet even if Democrats pursue these voters, there is some evidence that a post-industrial Ohio will more closely resemble its long-conservative neighbor Indiana, than its swing-state neighbors Pennsylvania or Michigan, in the elections to come.

The Ohio urban/rural political divide

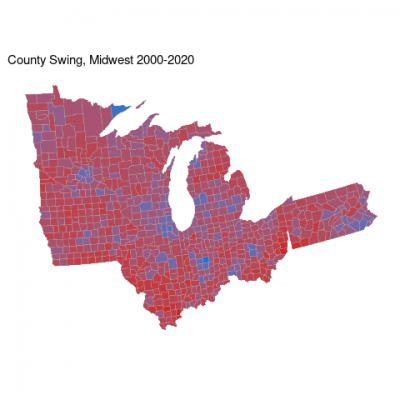

In many ways Ohio is merely mirroring trends within the greater Midwest. Over the past twenty years, urban areas have become more reliably Democratic while rural areas have become more reliably Republican. Several recent studies attribute differing explanations for this divide, but the outcome is an environment where metro areas are Democratic islands in a sea of Republican-dominated rural counties. Figure 1 shows the Democratic and Republican lean of counties in eight Midwestern states from 2000 to 2020, while Figure 2 shows the change in vote share from 2000 to 2020.

Figure 1 – Partisanship in counties in eight Midwestern states, 2000-2020

Figure 2 – Change in vote share in counties in eight Midwestern states, 2000-2020

Note: Deeper blue indicates a greater Democratic shift, while brighter red indicates a greater Republican shift.

Almost without exception, urban areas have become more Democratic and rural areas more Republican. The densely-populated counties that make up metropolitan Philadelphia in the southeastern corner of Pennsylvania have trended Democratic by as much as 20 percentage points, while even once-solid Republican urban counties such as crucial Waukesha county in Wisconsin have begun to shift left.

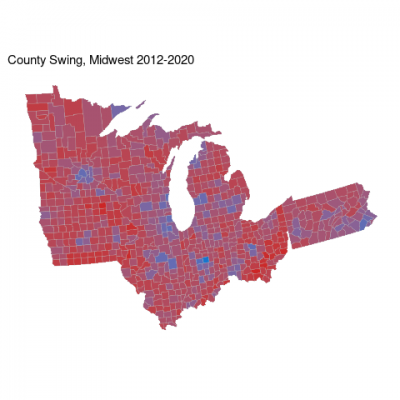

This polarization is particularly pronounced when comparing 2020 to 2012; nationwide, Obama’s re-election victory and Joe Biden’s victory look very similar. They each won 51 percent of the popular vote and competed across the Midwest, the South, and the Southwest. Even within the Midwest, Obama and Biden received nearly-identical vote shares in Minnesota and Illinois.

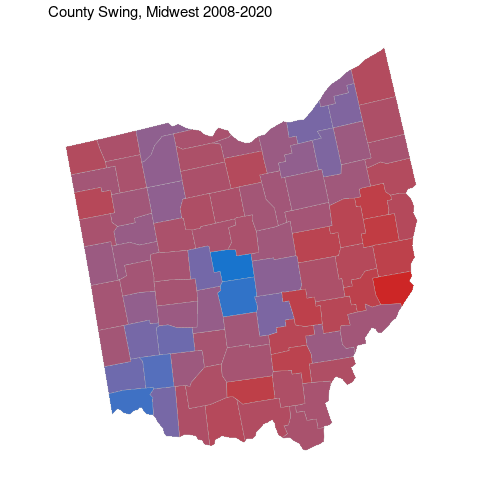

Yet here the similarities disappear. Biden underperformed Obama in the other six midwestern states, particularly Ohio (by 11 percentage points) and Iowa (by 14 percentage points). Figure 3 shows the shift in Midwestern counties from 2012 to 2020. Biden outperforms Obama in urban areas, while underperforming in rural areas. In Ohio, this overperformance was concentrated to the Cincinnati metro area in the state’s southwest corner, and the Columbus metro area in the middle of the state. By contrast, Biden lost considerable ground in the former coal-and-steel producing eastern third of the state. Additionally, northeastern Ohio – the Cleveland metro area – differs because it is a part of the country where the population has either stagnated or declined due to stresses from postindustrialization. It is therefore unsurprising that Democrats have lost ground there.

Figure 3 – Change in vote share in counties in eight Midwestern states, 2012 – 2020

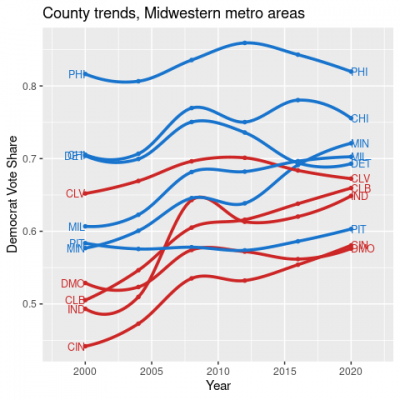

Not all Midwestern metros are equally pro-Democratic

Yet this urban-rural split masks considerable variation within metro areas. Ohio’s metro areas increasingly resemble those in Indiana – which has voted for Republicans in all but four elections since 1932 – than the urban areas of swing states Wisconsin, Michigan, or Pennsylvania. Figure 4 below shows the Democratic vote share of the eleven counties comprising the “core” of Midwestern metro areas between 2000 and 2020: Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati, Detroit, Indianapolis, Milwaukee, Chicago, Minneapolis, and Des Moines. All eleven counties have trended Democratic over the past twenty years. Yet of those six counties in states won by Joe Biden (in blue), Democratic vote share averaged 72 percent, while the five counties in states won by Donald Trump (in red), Democratic vote share was 63 percent. Further, vote share in Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati only averaged 64 percent.

Figure 4 – Democratic vote share across 11 Midwestern metro counties, 2000-2020

This is problematic for Ohio’s Democrats for two reasons.

First, its large three urban counties – in which the cities Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati are located – only represent 44 percent of Ohio’s population as of 2020. By contrast, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh represent 57 percent of Pennsylvania’s population, Minneapolis represents 51 percent of Minnesota’s population, and Chicago represents 69 percent of Illinois’ population. Democrats in these latter states do not need to appeal to rural and suburban voters to the same extent; they can rely on an urban-centric voter coalition and win.

Second, its metros are not as solidly Democratic as those in Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, or Wisconsin; Detroit, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Philadelphia regularly vote 70-30 for Democrats, while only 57 percent of Cincinnati voters went for Joe Biden. Instead, Ohio’s urban areas more closely resemble Indiana’s Indianapolis (27 percent of the state population; 65 percent Democrat vote share in 2020) and Iowa’s Des Moines (17 percent of the state population; 58 percent Democratic vote share in 2020), which are insufficient to overcome substantial deficits among rural voters.

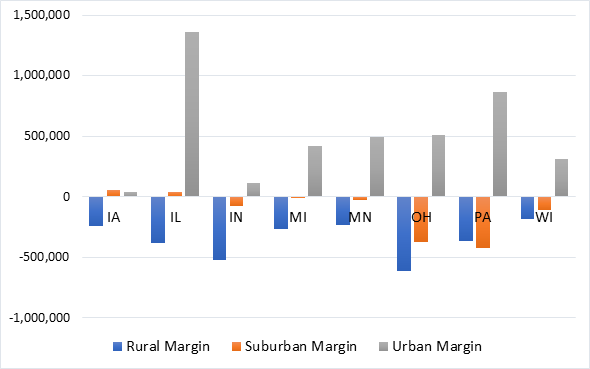

To underscore the challenge facing Biden’s re-election campaign in Ohio, consider Figure 5 below. In counties with fewer than 50,000 voters in 2020 – labeled “Rural” – Biden had a deficit of 615,000 votes in Ohio. This margin more closely resembles Indiana’s or Iowa’s margins than Pennsylvania and Michigan. Further, in counties with 50,000-250,000 voters in 2020 – labeled “Surburban” – Biden had a deficit in Ohio of 373,000 votes. While his deficit in Pennsylvania was similar, his deficit in Michigan and Wisconsin was not. At these margins, Democrats would need to build a majority of nearly 1 million votes – or 476,000 additional votes in urban counties – in order to win Ohio state-wide. For reference, Donald Trump won 592,000 votes in Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati combined in 2020, when voter turnout in the state was its highest in decades. It seems difficult to believe, bordering on impossible, that Democrats can win in Ohio without making substantial inroads among counties currently trending away from them.

Figure 5 – Biden’s 2020 election margins in rural, suburban and urban counties in eight midwestern states

“BIDEN HARRIS OHIO 2020” (Public Domain) by dankeck

Democrats’ inability to rely on urban counties means that the only path to victory is through the suburbs. Yet Ohio’s political history points to renewed challenges for Democrats in the suburbs as well. The “Inverted C” – which ran across Ohio’s northern, eastern, and southern edges – that allowed Democrats to win statewide as recently as 2006 and 2008 is now gone, perhaps irrevocably. In 2008, Barack Obama won 22 of Ohio’s 88 counties and 51 percent of the state’s popular vote; in 2020, Biden won only 6 counties and 45 percent of the state’s popular vote. The animated graphic – Figure 6 – below shows the Democratic and Republican lean of Ohio counties from 2000 to 2020:

Figure 6 – Party lean of Ohio counties, 2000-2020

And Figure 7 shows the swing in Ohio county vote share between 2008 and 2020:

Figure 7 – Ohio county vote share change, 2008-2020

To illustrate the Democratic dilemma in Ohio, consider two counties, one trending Democratic, and the other trending Republican: Stark and Delaware counties.

Stark county contains the Rust Belt city of Canton (south of Cleveland) and has seen its population stagnate at 375,000 over the past four decades as manufacturing declined in the region. In 2008, Obama won 97,000 votes in the county, to Senator John McCain’s 87,000. In 2020, Biden only won 76,000 votes in Stark County, while Trump won 111,000.

Delaware county (just north of Columbus) contains the fast-growing cities of Powell and Delaware and has seen its population quadruple from 54,000 to 210,000 over the past four decades. In 2008, Obama won only 37,000 votes to McCain’s 55,000, but by 2020, Biden won 58,000 votes to Trump’s 66,000.

Even at Delaware’s staggering population growth, it will take another two or three decades for the two counties to have an equal voting-eligible population. The coalition that Democrats have assembled nationwide may prove successful in 2024 – urban voters, minorities, women, and the youth vote may propel Democrats to further victories in North Carolina, Georgia, and Arizona – but it is not a recipe for victory in Ohio.

Ohio may now be out of reach for Democrats

What does all of this mean? It means that Joe Biden’s 2020 primary pitch – that he could appeal to the Rust Belt voters who cost Hillary Clinton the White House in 2016 – does not hold up in Ohio. And the alternative Democratic coalition – voters in urban metros – is insufficient to carry Democrats across the finish line in Ohio the same way Democrats can carry Minnesota, Illinois, or Pennsylvania. Instead, Ohio may be out of reach for Democrats in all but a handful of elections, akin to neighboring Indiana. While coalitions may change – Donald Trump’s victories in Ohio may be an aberration – the evidence suggests that Ohio is no longer a swing state.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/38HdoCN

About the author

Kevin Fahey – University of Nottingham

Kevin Fahey – University of Nottingham

Kevin Fahey is Assistant Professor at the University of Nottingham. He studies study political institutions and elite behavior, with specialization in subnational politics.

3 Comments