The 2020 US electoral cycle was truly historic. Along with two presidential candidates at odds with each other over policy, campaign decorum, and their visions for the future, it occurred in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic. Peter Finn, Madison Imiola, and Rob Ledger argue that if these two events are viewed as linked, rather than separate events happening at the same time, then we can gain a closer understanding of both. This understanding shows the need to reflect on election administration, misinformation, and lawsuits.

The 2020 US electoral cycle was truly historic. Along with two presidential candidates at odds with each other over policy, campaign decorum, and their visions for the future, it occurred in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic. Peter Finn, Madison Imiola, and Rob Ledger argue that if these two events are viewed as linked, rather than separate events happening at the same time, then we can gain a closer understanding of both. This understanding shows the need to reflect on election administration, misinformation, and lawsuits.

- Following the 2020 US General Election, our mini-series, ‘What Happened?’, explores aspects of elections at the presidential, Senate, House of Representative and state levels, and also reflects on what the election results will mean for US politics moving forward. If you are interested in contributing, please contact Rob Ledger (ledger@em.uni-frankfurt.de) or Peter Finn (finn@kingston.ac.uk).

As a US presidential election year, 2020 was set to be consequential regardless of the outcome. Throw into the mix a vacancy for the US Supreme Court and two candidates (one, President Donald Trump, an incumbent and the other, Joe Biden, a two term vice president) one of which who did not even practice the basics of campaign decorum, not to mention elections for the entire US House of Representatives, a third of the US Senate, and thousands of elections at state and local level, and the 2020 US electoral cycle would have been of historic importance no matter the broader context.

Yet, layered onto the 2020 cycle was the COVID-19 pandemic, a global health crisis that has driven domestic and international politics since early 2020. In the US, the pandemic had killed over 200,000 in the US by polling day, and over 500,000 more since. Moreover, rather than occurring in a vacuum, both the election and the pandemic were impacted by long term and pre-existing policies and structures.

Our research, suggests that we can better understand how both the election cycle and the pandemic evolved in 2020 when we consider them as related rather than separate phenomena happening at the same time. Doing so helps increase the understanding of how long term and pre-existing policies and structures impacted both. This understanding suggests a need to reflect on the following interrelated policy themes: election administration; misinformation and mail-in voting; lawsuits.

Election Administration

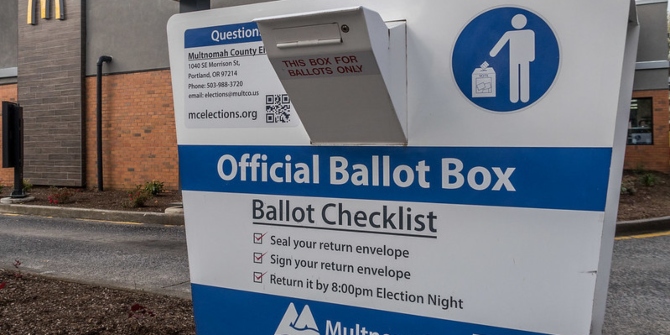

Running elections in a country as large and diverse as the US is complex and costly. Without continual investment in people, processes, and infrastructure, the ability of those responsible for running elections to do so becomes much more difficult, with a concurrent decrease in the ability of voters to engage in the democratic process.

>In 2020, 18 out of 57 Democrat primaries were suspended at least once. Of note here is that no primaries or caucuses were actually suspended until the Ohio Primary on March 17th. By this point 27 Democratic primaries and caucuses had already been held (with three more held on March 17th itself), meaning that, of the remaining 27 primaries and caucuses, the majority did not occur as initially scheduled.

Across the US, important adaptations were made at speed, and under conditions of significant stress during a period of political polarisation, to facilitate the 2020 election cycle. Yet, there were clear issues with election administration. Indicative examples included the cutting of the number of polling stations from 180 to 5 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (with a similar picture in Green Bay), in that state’s primary. This contributed to lines that were reported to be as long as four hours in Green Bay. In Ohio, meanwhile, as per Dayton Daily News reporting, at least 9,000 primary voters in the Dayton area were unable to vote because ballot requests were ‘mailed too late’ or were ‘improperly filled out’: with ‘ballot request forms mailed before the election’ continuing to arrive at ‘local elections boards for days after the primary election day’ in late April. This after the cancellation of the original Ohio primary on March 17th with just hours notice despite weeks of early voting having already occurred.

Thinking about how and why these issues arose and how they could be prevented in the future is likely to pay dividends, whether in a future pandemic or another major crisis. In short, there is a need for policy makers at local, state and territory, and federal level to reflect on the 2020 cycle and learn lessons from it.

Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash

Misinformation and mail-in voting

A key theme to emerge from the above discussions is the perpetuation of misinformation. Most obviously, one can observe this in Trump’s continual questioning of election results and mail-in voting processes. For much of 2020, Trump and those associated with and supporting him, made erroneous claims about voter fraud, often with relation to mail-in voting. Following the election itself, the window between polls closing and the counting of mail-in ballots created an opportunity for erroneous claims of voter fraud to gain traction. This continual questioning of Biden’s victory culminated in the attack on the US Capitol on January 6th 2021.

As illustrated by Priscilla Southwell of the University of Oregon, academic research on mail-in voting in states that have used it extensively for decades demonstrates that such claims are unfounded. This is not to dismiss genuine concerns about the administration of mail-in voting, especially in a year when use of the practice grew greatly both in primaries and in the general election. Yet, such concerns must be separated from baseless attempts to discredit mail-in voting and question election results in a manner designed to disenfranchise millions.

Moving forward, if, as seems likely, mail-in voting remains central to US elections, there is a need to think about how to manage this. Examples of how to do so, such as processing mail-in ballots prior to polls closing and having clear processes for voters to correct mistakes (known as ballot curing), can be seen in election administration in many states. Moreover, if states continue to prevent the counting of mail-in ballots until after polls have closed, then clear messaging about the time it will take to count mail-in ballots, and the effect it may have on initial, but partial, results, is important. In short, there is a need to manage expectations about the speed of results.

Lawsuits

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a raft of legal cases related to the 2020 electoral cycle. However, resorting to legal means to resolve electoral disputes is not new in US politics, nor is it necessarily illegitimate. Indeed, some cases related to the 2020 electoral cycle, most obviously those lodged to resolve disputes about the safest time and manner to hold elections during a pandemic, may well have been the most judicious way to decide between differing viewpoints on pressing matters of administration.

However, arguably during some 2020 primaries the filing of lawsuits came to dominate over the process of voting itself. Indeed, in New York some Democrats ‘preemptively filed suit’ against fellow Democrats before any votes had actually been counted, thus establishing ‘their right to challenge their opponents’ votes’.

Following Biden’s victory in the presidential election in November, Trump and those supporting and aligned with him, launched legal cases on scant evidence questioning how elections had been run in numerous states, thus in-turn questioning the overall election result. Any lingering concerns that these lawsuits would be successful were dispelled on December 11 when the US Supreme Court dismissed a case lodged by the Texas attorney general challenging how elections had been conducted in Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Building on the work of Wendy Scattergood of St. Norbert College in Wisconsin, it is hard not to conclude that reflection is needed across the political spectrum at local, state and territorial, and the federal level about the place of courts in US elections.

The next crisis to impact US elections may look very different from the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, it is important not to attempt to develop solutions wholly targeted at the logistical issues that arose during the last electoral cycle. That said, the above themes link with long term trends, and suggest the need to think about how resilience can be built into the US elections at all levels moving forward.

- This article is based on the briefing paper, Pandemic Politics: COVID-19 and the 2020 US Electoral Cycle.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3aXqJrX

About the authors

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Dr Peter Finn is a multi-award-winning Senior Lecturer in Politics at Kingston University. His research is focused on conceptualising the ways that the US and the UK attempt to embed impunity for violations of international law into their national security operations. He is also interested in US politics more generally, with a particular focus on presidential power and elections. He has, among other places, been featured in The Guardian, The Conversation, Open Democracy and Critical Military Studies.

Madison Imiola – Washington State Human Rights Commission

Madison Imiola – Washington State Human Rights Commission

Madison Imiola is an MA Human Rights Graduate (2020) from Kingston University. She now works as a Civil Rights Investigator with the Washington State Human Rights Commission.

Robert Ledger – Schiller University

Robert Ledger – Schiller University

Robert Ledger has a PhD in political science from Queen Mary University of London. He has worked for the European Stability Initiative, a think-tank in Brussels, lectured at several universities in London and currently lives in Frankfurt am Main. He is a Visiting Researcher (Gastwissenshaftler) in the History Seminar at Goethe University and also teaches at Schiller University Heidelberg and the Frankfurt School of Finance & Management. He is the author of Neoliberal Thought and Thatcherism: ‘A Transition From Here to There?’