Can comedians and entertainers make a difference in politics all the way to the top? In new research, Brian Calfano and Lori Han examine the influence of the host of The Tonight Show, Johnny Carson’s mentions, between 1972 and 1974, of the Watergate scandal and President Richard Nixon. They find that Carson’s comments on Watergate likely influenced public opinion which then encouraged further news coverage of the scandal, leading to falling ratings for President Nixon.

Can comedians and entertainers make a difference in politics all the way to the top? In new research, Brian Calfano and Lori Han examine the influence of the host of The Tonight Show, Johnny Carson’s mentions, between 1972 and 1974, of the Watergate scandal and President Richard Nixon. They find that Carson’s comments on Watergate likely influenced public opinion which then encouraged further news coverage of the scandal, leading to falling ratings for President Nixon.

Often, humor provides an entertaining escape from life’s challenges. But humor may also be educational. Americans rely on television comedians as cultural lenses to help make sense of current events. The ubiquity of “soft news” (content which primarily entertains rather than informs) reinforces television comedy as a popular communication platform. It is not surprising, therefore, that public opinion data show that sizeable percentages of Americans claim to be politically informed and engaged from watching television political comedy. But most research has been generally occupied with today’s more confrontational form of late night political humor. Laughs from the broadcast era of the mid-late 20th century are passé.

Assessing Late Night TV’s influence on sentiment about Nixon and Watergate

We address this gap by assessing the influence of perhaps the most famous American late-night television comedian in history—Johnny Carson—on public opinion about one of the most influential American politicians of the twentieth century—Richard Nixon during Watergate. In terms of legacy, Carson, who hosted NBC’s The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson from 1962-1992, is generally considered the standard bearer for the two generations of late-night comedic hosts who followed him. Conventional wisdom suggests that Carson’s stature provided him some measure of public opinion influence. But not only were television options far more limited for viewers in Carson’s era, political polarization was far lower. With a large and politically diverse audience, Carson faced criticism for not taking on “serious” issues. Carson did, in fact, make political jokes—it’s just that the content (and timing) were different.

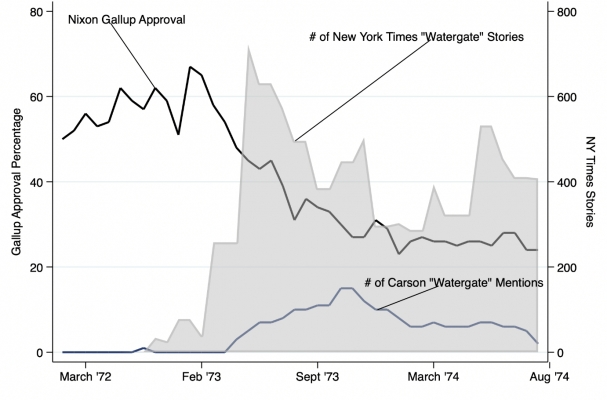

Figure 1 includes Nixon’s Gallup approval ratings, the number of Carson mentions of President Nixon and/or Watergate, and New York Times mentions of the same between 1972-1974. While Carson accelerated his mentions of Watergate in fall 1973 and winter 1974, he mentioned Watergate less frequently when it appeared that Nixon would either be impeached or forced to resign. This is part of the content and timing difference with Carson: he was not one to pile on.

Figure 1 – President Nixon’s Gallup ratings by NY Times and Carson Mentions

The Figure 1 Gallup line suggests that if Carson did influence public opinion about Nixon, he likely could not unilaterally move it (even if he wanted to). The reason for this is steeped in the reality of what makes political humor funny: humor requires shared meaning between the comedian and audience. As such, a different way to think about Carson’s potential influence was that he focused additional audience attention on a topic after media coverage ramped up.

We use a count measure of Carson’s “Watergate” and/or “Nixon” mentions based on transcripts of The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson during this period (not including guest hosts). Since any part of a late-night talk show can contain political content, we examined each show’s entire transcript (including interviews and sketches) for relevant mentions. We also drew on NBC Broadcast Standards Department summaries of Tonight Show episodes and Tonight Show talent coordinator notes for information about show content.

Photo by Ajeet Mestry on Unsplash

We coded “Watergate,” “Nixon,” and other associated terms (including “John Dean,” “Judge Sirica,” “Haldeman,” “Ehrlichman,” “Rose Mary Woods,” “Senator Ervin,” “John Mitchell,” etc.) into “pro”/ “con”/or “neutral” categories. The challenge with this tactic, however, is that whatever conventional wisdom might have us remember about Carson’s political humor, he made relatively few mentions of the scandal on the air. This means that there are an even smaller number of cases where Carson used a decisively negative tone. The directional variables had no statistical effect on Nixon’s approval rating.

A good case for Carson’s influence on Nixon’s approval

We first estimate a model of Nixon’s Gallup approval ratings from February 1972 to August 1974 and controlling for national policy “mood,” the monthly number of “Watergate” mentions in The New York Times, monthly unemployment, and quarterly GDP. The punchline: A one-unit increase in Carson’s mentioning the Watergate scandal in some way lowered Nixon’s Gallup rating by 1.4 points over the time series. Lacking statistical significance, however, is the number of New York Times mentions. This may be partially due to the paper’s largest upward swing occurring just after Nixon’s Gallup rating began its winter 1973 slide. Using “skeptical” Bayesian priors in separate models, however, we can undermine Carson’s influence to the point the New York Times mentions are causal (and Carson’s mentions are not). This will satisfy critics who can’t accept that a television comedian could affect public opinion. But, taken in total, the models suggest a good case for Carson influencing Nixon’s approval, even if one wants to give the news media most of the credit.

Our statistical findings underscore the “relay” race dynamic that Russell L. Peterson described in his 2008 book, Strange Bedfellows: How Late-night Comedy Turns Democracy Into a Joke, between news and late night comedy of the era. This makes us the first to conclude that the conventional wisdom was correct: what Johnny Carson said on The Tonight Show affected public opinion, at least when it came to Nixon’s approval rating and in the wider context of media coverage of the scandal. We probably should have expected nothing less from the “King of Late Night.”

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Nothing funnier than the news: Assessing Johnny Carson’s comedic effect, past and present’, in Social Science Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/32lPTQs

About the authors

Brian R. Calfano – University of Cincinnati

Brian R. Calfano – University of Cincinnati

Brian Calfano is an Associate Professor of Political Science and Journalism at the University of Cincinnati. He has 50 peer-reviewed journal articles to his credit and is the co-author of God Talk: Experimenting with the Religious Causes of Public Opinion (Temple University Press, 2013), A Matter of Discretion: The Political Behavior of Catholic Priests in the U.S. and Ireland (Rowman and Littlefield, 2017), and Human Relations Commissions: Relieving Racial Tensions in the American City (2020 Columbia University Press).

Lori Han – Chapman University

Lori Han – Chapman University

Lori Cox Han is Professor of Political Science, Doy B. Henley Chair of American Presidential Studies and the Director of Presidential Studies Program at Chapman University. Her research and teaching expertise include the presidency, women and politics, media and politics, and political leadership.

Have you read “Some of the Things Jon Stewart Hates About the Media are Jon Stewart’s fault?” What do you think?