In Unexpected Voices in Imperial Parliaments, editors Josep M. Fradera, José María Portillo and Teresa Segura-Garcia bring together contributors to examine the careers of nine colonial subjects who became legislators in imperial parliamentary institutions from the time of the French Revolution to the Second World War. In exploring the norm-shattering voices of these figures as well as the challenges they faced, this book offers an urgent reflection on the promises and limitations of liberalism in our contemporary moment, writes Dinyar Patel.

Unexpected Voices in Imperial Parliaments. Josep M. Fradera, José María Portillo and Teresa Segura-Garcia (eds). Bloomsbury. 2021.

We live in an era where being a legislator can be downright dangerous. In the United States, thanks to the continued threat from armed conspiracy theorists, the Capitol was until very recently surrounded by a cyclone wire-topped fence. In retreating democracies like India, Hungary, the Philippines and Brazil, representatives of the political opposition have been subjected to violence, intimidation and an avalanche of horrific online threats.

We live in an era where being a legislator can be downright dangerous. In the United States, thanks to the continued threat from armed conspiracy theorists, the Capitol was until very recently surrounded by a cyclone wire-topped fence. In retreating democracies like India, Hungary, the Philippines and Brazil, representatives of the political opposition have been subjected to violence, intimidation and an avalanche of horrific online threats.

It might therefore be worthwhile to remember another moment of intense precarity: when legislators of different ethnicities and skin colours joined assemblies of otherwise all-white, elite men. This is the focus of Unexpected Voices in Imperial Parliaments, which brings together chapters on nine such representatives from the time of the French Revolution to the Second World War. African, black, mixed race, indigenous and Indian, these individuals are drawn from an eclectic mix of lawmaking bodies: from the Cape Provincial Council, South Africa, to the British House of Commons; from the Senate of Antioquia — a briefly existent republic in modern-day Colombia — to the Cortes in Cádiz, Spain. Taken together, the accounts illustrate the promises and limitations of liberalism, topics of obvious contemporary relevance.

One of the most important accomplishments of this volume is to shine new comparative light on imperial systems, illustrating different ways in which disadvantaged subjects could acquire power and influence. The Spanish, British and American empires get their due, but it is within the French Empire that some of the most exciting episodes took place. We learn of a Haitian ex-slave who joined the National Assembly during the Jacobin Republic (1792-94) and a black deputy from Guadeloupe who had personal access to Marshal Pétain during the Vichy Republic (1940-44). Throughout the nineteenth century, Indians unfavorably compared their political status under British colonial rule to that of French imperial subjects. Several chapters in Unexpected Voices validate Indians’ complaints and illustrate the dramatic mobility which some non-Europeans achieved under the French tricolore.

Image Credit: ‘Cádiz 1812’ by Alfonso Jimenez licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

The first two chapters are concerned with debunking mythical accounts. Jean Baptiste Belley, the Haitian in revolutionary Paris, was depicted in C. L. R. James’s The Black Jacobins as giving the decisive speech behind the National Convention’s decision in 1794 to abolish slavery. David Geggus demonstrates that this was not the case. Belley would have had difficulty saying anything in the National Convention: he was most comfortable speaking in Creole, which was unlikely to be understood by many other deputies. Instead of oration, Geggus argues, Belley’s importance was being ‘a metaphor for slave emancipation’: a symbol of the French Revolution’s universalist promise — at least before the Thermidor chill.

José Maria Portillo examines the life of Dionisio Inca Yupanqui, a Peruvian native who enthralled fellow delegates at the Cortes of Cádiz by proclaiming his Incan noble heritage. Unfortunately, Portillo notes, this was a fabrication, the unintended consequence of the Spanish crown’s attempt to cement the loyalty of American colonial elites. Portillo’s account briefly alludes to the career of José Miguel Guridi, who represented Tlaxcala (in modern-day Mexico) at Cádiz. I would have liked to hear more about him — he seems far more interesting than the Incan impostor. As the Cortes equivocated about granting equal rights to colonial subjects, Guridi deployed sophisticated arguments in favour of the idea. There was no point excluding colonial subjects because they looked and dressed differently or spoke different languages: similar diversity could be found within peninsular Spain and did not lead to exclusion. These arguments bear striking similarity to those developed some 60 years later by Indians demanding representation in Westminster.

Yupanqui led a relatively charmed life, but Belley had been imprisoned when he first arrived in France and spent some of his last years in detention. The lives of others profiled in this book were intertwined with different degrees of precarity. Cyrille Bissette — a free person of colour from Guadeloupe and, incredibly, a relative of Empress Joséphine Bonaparte — was at the centre of white planters’ purge of black economic power from the island in the 1820s. He was exiled and branded as a slave with a hot iron before winning some reprieve in France, thereupon embarking on a political career. Abel Alexis Louis’s chapter on Bissette portrays a black man, a slaveholder and a defender of the slave order, who underwent a radical evolution in Paris, becoming a pathbreaking advocate of abolition.

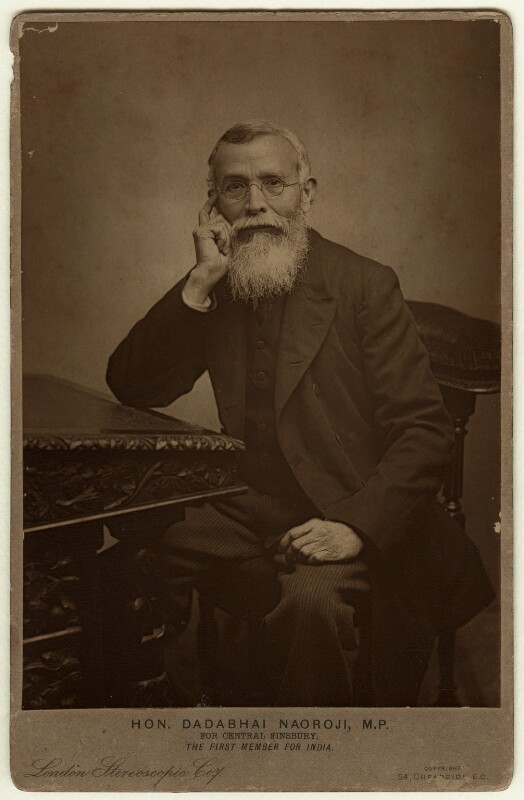

Daniel Gutiérrez Ardila introduces us to Pedro José de Ibarra, a highly educated pardo (person of mixed African and European heritage) who became a senator in Antioquia. His livelihood and career, nevertheless, were limited by crushing racism, something which even prevented him from marrying. Like Bissette, Ibarra was a slaveholder, demonstrating the complex world of freedom and unfreedom in black colonial societies. Teresa Segura-Garcia chronicles the racism Dadabhai Naoroji encountered while standing for election to the British Parliament in the 1880s and 1890s. This was far less severe than that encountered by Ibarra, perhaps, as Segura-Garcia notes, because of Naoroji’s light skin colour and ‘mild, gentlemanly masculinity’ (Tory opponents still had a field day whipping up hysteria over a ‘fire-worshipper’ in the House of Commons).

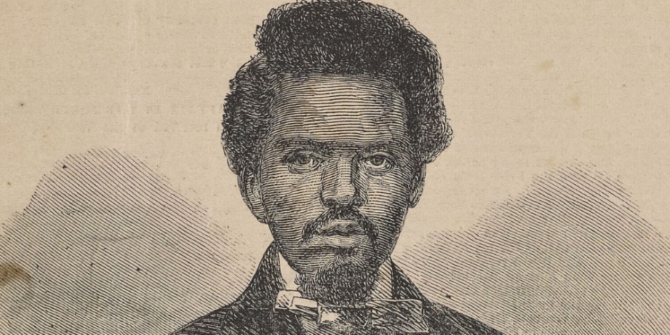

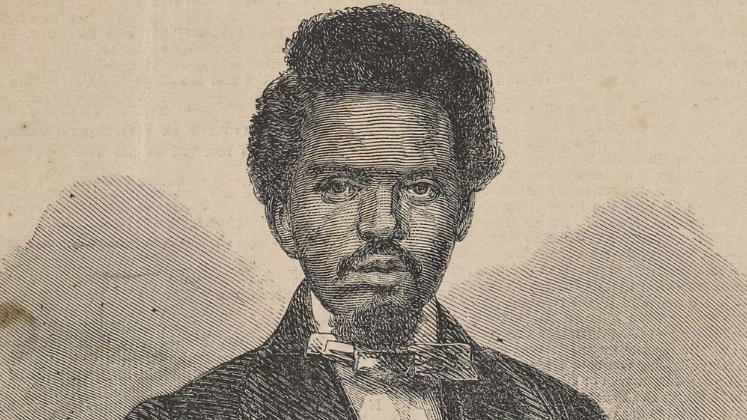

Image Credit: Crop of ‘Robert Smalls, captain of the gun-boat “Planter” ; The gun-boat “Planter,” run out of Charleston, S.C. by Robert Smalls, May, 1862’ from The New York Public Library, no known copyright restrictions.

This leaves us with four remaining legislators, all of them African or from the African diaspora, and all of them possessing remarkable life stories. Robert Smalls — a slave from Beaufort, South Carolina — shot to fame in the American Civil War by piloting a Confederate steamship out of Charleston Harbour and delivering it to Union forces. In Stephanie McCurry’s account, Smalls, who sat in both the South Carolina state house and the US House of Representatives, outlasted the end of Reconstruction through both canny political skill and unmatched bravery. He survived multiple attempts on his life, providing fellow Congressmen with an unvarnished account of the violence, voter intimidation and fraud which white South Carolinians were deploying to roll back black people’s achievements under Reconstruction. (When I taught in South Carolina, Smalls was finally getting his public due in the state, featuring prominently in a new national monument in Beaufort.)

Timothy Stapleton profiles Mpilo Walter Benson Rubusana, a Xhosa who, in 1910, tested the limits of the Cape Province’s liberal tradition by winning election to its provincial council. He was the last black person elected to a South African legislature before the end of apartheid in 1994. Stapleton’s chapter gives a particularly nuanced portrait of emerging black South African politics in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, revealing a movement unfortunately undermined by personal rivalries (J. T. Jabavu, who published South Africa’s first independent black newspaper, actually campaigned against Rubusana’s election).

The last two chapters return us to the French Empire. Dominique Chathuant charts how Gratien Candace, the grandson of a Guadeloupean slave, reached the heights of political power in interwar France, becoming a government minister and Vice President of the Chamber of Deputies in 1938. Candace remained as a deputy during the Vichy Republic, protesting to Marshal Pétain about persistent racism and the deportation of Jews. This begs the question: was Candace living in a fantasy world? Chathuant needs to tell us much more about how a black deputy made peace with the Vichy regime, and how he undertook the intellectual somersault of being a committed republican at this dark moment in French history.

Erica Garcia-Moral writes about the plucky Senegalese representative Blaise Diagne in what was my favourite chapter in this volume. Garcia-Moral brings out the utter complexity of the French Empire: how particular regions, such as Senegal’s Four Communes, could exercise extraordinary political power. Diagne, who shocked colonial authorities by marrying a white French woman, caused them further headaches by relentlessly campaigning for French citizenship for residents and descendants of the Four Communes and using his position to advance the interests of the West African colonies. His amassing of African political power pushed one colonial governor to resign and another to declare ‘that France no longer ruled the country’.

Unexpected Voices provides a wealth of information on these nine legislators but does not adequately highlight connective tissue. It is certainly there, buried amidst the pages. Masonry emerges as an institution of critical importance in smoothing over racial prejudices. French Masons came to Bissette’s assistance as he fought for rights for free people of colour. Candace joined the Masons while a schoolteacher in the French Pyrenees and Diagne, as an imperial customs officer, demanded to be posted only in colonies where there were Masonic lodges. Naoroji relied on Masons for British and Indian political connections and dashed from one late-night lodge meeting to another in Central Finsbury before his election as an MP in 1892.

Aside from the Masonic lodge, another institution of preeminent importance was the schoolhouse. Ibarra benefited from private tuition — there were no primary schools in Antioquia in the early 1800s — and gained prestige as a tutor for the children of the province’s elites. Naoroji claimed to have launched his public career out of gratitude for receiving free, state-supported schooling in Bombay. Diagne was fortunate enough to have his education sponsored by a French Creole in Senegal.

Education had a particularly transformative role for Candace and Rubusana. The école républicaine, Chathuant tells us, helped propel Candace’s professional and political rise. Rubusana was an intellectual giant: he produced the ‘first major book published in IsiXhosa’ for which he was granted an honorary doctorate from a black American college. As a leading educationalist, he championed compulsory schooling for Africans and the establishment of a ‘native college’. Smalls, for his part, was denied a formal education as a slave, something which no doubt pushed him to become a vocal advocate of education for his newly freed compatriots. McCurry identifies education as his ‘singular issue’ as a legislator: Smalls might have laid the foundations for the modern public school system in South Carolina. From all these cases, it is abundantly clear how colonial subjects (and ex-slaves in the US South) understood that education was not simply a means for socioeconomic advancement but the pathway towards full political rights.

Image Credit: ‘Dadabhai Naoroji by London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company, published by Messrs R.M. Richardson & Co, sepia-toned carbon print cabinet card, circa 1892, NPG x128698′ licensed by The National Portrait Gallery under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Many of these legislators fell into two camps: those who persisted in their radical outspokenness, like Smalls or Naoroji, and those who moderated their views over time. Political moderation was a symptom of the precarious position of these men. After the abolition of slavery in France in 1848, Bissette sought reconciliation with his former white oppressors, earning him the ire of Guadeloupe’s free people of colour. He even renounced his earlier views that slaveholders should not be compensated after abolition. Rubusana, once a radical voice, found himself out of step in black South African politics by the First World War. Candace alienated black people through his soft position on Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia. We can explain his participation in the Vichy regime through his obsession with compromise in the interest of black-white concord.

But it is Diagne who provides us with the most dramatic instance of a political volte-face. Diagne built his career through opposition to Bordeaux commercial interests in Senegal but then forged an alliance with them. He broke with black communists (tellingly, the French Communist Party’s mandate to give up Masonic affiliation was a factor behind Diagne’s opposition) and Pan-Africanism, earning the full-throated antagonism of black intellectuals by the 1930s.

In all of these cases of political moderation, we can witness an abiding worry about going ‘too far’ in testing the limits of European liberalism. It is no coincidence that the rise of these leaders sparked furious, violent backlashes amongst white elites: the steady whittling away of the Cape Liberal Tradition in South Africa after Rubusana or French attempts in Senegal to balance out Diagne with traditional tribal leaders (perhaps taking a page from the British Raj’s successful strategy of using Indian princes against nationalists). Bissette, Candace and Diagne were all committed assimilationists, believers in the French Empire’s civilising mission. Perhaps it was too dangerous for them, as bridges between colonial and metropolitan society, to cast serious doubts upon their convictions.

It would be worthwhile knowing more about what these nine leaders thought of one another. There are some connections — many of the late nineteenth and early-twentieth-century figures were in touch with W. E. B. Du Bois. Naoroji’s career interested both Du Bois and Rubusana’s nemesis, Jabavu, while Rubusana’s election was celebrated by an Indian whom Naoroji occasionally mentored, the future Mahatma Gandhi. Aside from Masonry, abolitionism probably facilitated intellectual contact, as did, eventually, championship of other political movements. Naoroji campaigned for female suffrage, as did Candace, who, in a moment of weighty symbolic significance, stood before the French Chamber of Deputies and compared women’s suffrage to the abolition of slavery. We know, from works by scholars like C. A. Bayly, that Indians assiduously studied colonial political representation in other European empires. Surely some of these nine legislators must have examined the careers of one another or, in the case of Candace and Diagne, whose parliamentary careers overlapped, engaged in vigorous conversation.

Women’s voices are mostly absent in this volume, more the fault of history itself rather than the contributors’ neglect. However, if the Reconstruction-era US Congress can be classified as an ‘imperial parliament’, there is certainly also scope for including pioneering female legislators who broke up male bastions in Europe and America.

Finally, we must consider whether these nine legislators truly were ‘unexpected voices’. Smalls was part of a cohort of ex-slaves ushered into the halls of power during Reconstruction — not an unexpected voice, therefore, but certainly an unwelcome one to many of his colleagues. Naoroji’s election was not completely unexpected: Indians had been standing for Parliament for seven years prior to his win, and the first ever Indian to do so, Lalmohan Ghosh, narrowly lost in 1885. France’s established track record of incorporating black legislators meant that Candace and Diagne were probably not unexpected either, although their vertiginous political rise was certainly exceptional.

Not all of these voices were unexpected, but they were deeply unsettling and norm-shattering. And — as we know from the continuing violent ‘whitelash’ after the presidency of Barack Obama, the rise of far-right parties in Europe and Hindutva’s politics of resentment in India — the shattering of even the most repugnant norms can invigorate dangerous opposition to liberalism. The nine lives in this volume therefore speak with a certain sense of urgency to the contemporary reader. They inspire belief in liberalism’s universalising potential. Yet they remind us that small-minded human prejudice can be an equally potent universal force.

- This review first appeared at LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3xBW4eC

About the reviewer

Dinyar Patel – S. P. Jain Institute of Management and Research in Mumbai

Dr Dinyar Patel is Assistant Professor of History at the S. P. Jain Institute of Management and Research in Mumbai. He is the author of Naoroji: Pioneer of Indian Nationalism (Harvard University Press, 2020), which won the 2021 Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay NIF Book Prize.