The capitol insurrection of January 6, 2021 brought the rise of political violence in America into sharp focus. But who supports the use of violence to achieve their political goals? In new survey research, Miles T. Armaly and Adam M. Enders find that feelings of victimhood, authoritarian and populist sentiments and white identity have the strongest link to support for political violence. They also find that support for political violence is not closely linked to support for a political party, nor is it widespread, with only 13 percent of respondents supporting it.

The capitol insurrection of January 6, 2021 brought the rise of political violence in America into sharp focus. But who supports the use of violence to achieve their political goals? In new survey research, Miles T. Armaly and Adam M. Enders find that feelings of victimhood, authoritarian and populist sentiments and white identity have the strongest link to support for political violence. They also find that support for political violence is not closely linked to support for a political party, nor is it widespread, with only 13 percent of respondents supporting it.

In recent years, the American public has witnessed an increase in support for, and the use of, political violence. While the most obvious example is the deadly riot at the US Capitol Building on January 6, 2021, politically motivated violence has been on the rise more generally; there were many smaller acts of political violence in 2016, such as attacks on protestors during political rallies. In addition to witnessing the actual use of violence, American politics has grown more politically polarized, and individuals are more distrustful of government and more hostile toward groups that they don’t identify with. As such, it is worth considering who, exactly, supports the use of violence to achieve their political goals.

Researchers have been studying support for political violence for decades. Indeed, much is known about the national or global conditions that foster violence (e.g., economic inequality has long been tied to violence). However, previous research has sought to explain support for violence using individual or small groups of attitudes about violence, rather than focusing on who is most likely to support violence. In our research, we examine the predictors of support for political violence with the aim of constructing a more comprehensive list of the potential predictors of violence than previous research has offered and generating a predictive profile of the characteristics displayed by individuals who are likely to support violence (i.e., of who might agree with statements like “Violence is sometimes an acceptable way for Americans to express their disagreement with the government.”).

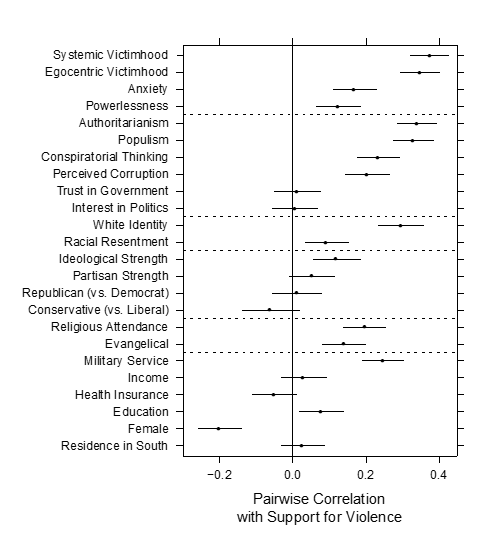

In all, we identified 24 potential predictors of support for political violence, some previously identified and others unique to our analysis. These predictors span many domains, including the psychological (e.g., perceived victimhood), government attitudes (e.g., trust in government), racial attitudes and identities (e.g., racial resentment), political identities (e.g., partisanship), and religious and demographic characteristics. Correlations between these predictors and support for political violence vary considerably, as can be seen in Figure 1, which shows the results of our survey research. Feelings of victimhood, authoritarian and populist orientations, and white identity show the strongest relationships.

Figure 1- Correlations between support for political violence and 24 individual-level characteristics, with 95 percent confidence intervals

Since many of these characteristics are highly correlated not only with support for political violence, but with each other, we utilized a machine learning-based methodology to determine which characteristics were most predictive of support for political violence when accounting for other factors. We found that six characteristics are particularly useful in accounting for support for political violence:

- Perceived systemic victimhood (e.g., “The system works against people like me”)

- Support for populism (e.g., “I’d rather put my trust in the wisdom of ordinary people than the opinions of experts and intellectuals.”)

- Racial resentment (e.g., “It’s really a matter of some people not trying hard enough; if blacks would only try harder, they could be just as well off as whites.”)

- Authoritarianism (e.g., “People should leave important decisions to those in charge/the leaders”)

- White identity (e.g., “Being white is important to my identity.”)

- Current or past military service

“Connecticut Avenue” (CC BY 2.0) by Mike J Maguire

Finally, we used these characteristics to create a psychological profile of individuals who are most likely to support political violence in general and tested it by using it to predict support for the January 6 riot specifically. In doing so, we also examined the role of support for Trump since the riots are unlikely to have occurred had President Trump’s “Save America” rally not occurred. We find that the effect of the political violence profile on support for the riot is on par with the effect of support for Trump. Moreover, when considering the political violence profile (PVP) and Trump support together, we see that the effect of the PVP on support for the 1/6 riot is the most pronounced for the strongest Trump supporters.

Political violence is not partisan nor widespread

Our results indicate that support for political violence is associated with several political, psychological, and social characteristics. While most of the Capitol rioters were Republicans (or at least supportive of Trump), violence does not appear to be a partisan phenomenon. Indeed, with the exception of military service, psychological orientations regarding power (i.e., authoritarianism and populism) and racial groups (i.e., white identity and racial resentment) are the most predictive of support for violence.

It is critical to note, though, that support for political violence is not particularly widespread. Only around 13 percent of respondents support political violence, and 10 percent are neutral. Nevertheless, the number of individuals high in the suite of characteristics identified by our analysis is surely in the millions. Moreover, we know it only takes a handful of people to cause death and destruction.

The January 6 Capitol riot surely made political violence less abstract for most Americans. While attempting to predict individual acts of violence (e.g., terrorism) is a tricky endeavor, understanding who supports political violence can aid scholars and law enforcement in anticipating and preventing acts of violence. We argue that identifying the individual characteristics that underscore support for violence is a useful first step.

- This article is based on the paper: ‘Who Supports Political Violence?’ in Perspectives on Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3n83wtj

About the authors

Miles T. Armaly – University of Mississippi

Miles T. Armaly – University of Mississippi

Miles T. Armaly is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Mississippi. His research focuses polarization and mass attitudes toward the US Supreme Court

Adam M. Enders – University of Louisville

Adam M. Enders – University of Louisville

Adam M. Enders is assistant professor of political science at University of Louisville.