In Cut/Copy/Paste: Fragments from the History of Bookwork, Whitney Trettien explores how seventeenth-century English publishers cut up and reassembled paper media into radical, bespoke publications, arguing that this ‘bookwork’ contributes to understanding digital scholarship and publishing today. Through its magnetic prose that narrates weird and joyous entanglements with the printed word, Trettien reveals that the lives of books are longer and stranger than we imagine, writes Sam di Bella.

Cut/Copy/Paste: Fragments from the History of Bookwork. Whitney Trettien. University of Minnesota Press. 2021.

Digital thinking predates the computer, Cut/Copy/Paste proposes. In a kaleidoscopic analysis, media historian Whitney Trettien arrays an entire vista of seventeenth-century publishing beyond the bite of a printing press. Instead, scissors, glue and inky revisions are at the centre of Trettien’s ‘bookwork’: defined as both the work done to make books and the work done with books.

Digital thinking predates the computer, Cut/Copy/Paste proposes. In a kaleidoscopic analysis, media historian Whitney Trettien arrays an entire vista of seventeenth-century publishing beyond the bite of a printing press. Instead, scissors, glue and inky revisions are at the centre of Trettien’s ‘bookwork’: defined as both the work done to make books and the work done with books.

The three extended cases that comprise Cut/Copy/Paste — the evangelical ‘harmonies’ of the Little Gidding household; the queer, overflowing editions of Edward Benlowes; and John Bagford’s ephemeral print histories — all show how seventeenth-century English publishers could employ and encourage the freewheeling association that hypertext once promised to deliver. How do we know? By the traces of their work, Trettien argues.

Trettien constructs a model for a philosophy of book fragments through the fields of book history, science and technology studies and media archaeology. For the latter, she avoids what she calls its ‘unapologetic presentism’ (24) by drawing on feminist materialist methods that consider relationships as much as objects. Rather than a history of the solo-authored codex, Cut/Copy/Paste is a history of miscellanies, messy collections and Sammelbands — codices bound up with multiple texts within them. The result recognises the communal nature of book authorship and production:

Hand-assembled volumes offer a vision of the book as a synthetic publishing technology that materially gathers and processes the past for future readers. This is the codex as both curiosity cabinet and binding thread, as a bespoke library before the existence of libraries as we know them, as a staging ground to marshal fragmented media into new reading machines.’(7)

Yet despite having and referring to so many fragments, Cut/Copy/Paste itself doesn’t feel fragmented, and its prose is magnetic (a rarity in an academic text). I enjoyed reading Cut/Copy/Paste, a weird and joyous book about people doing weird and joyous things with books.

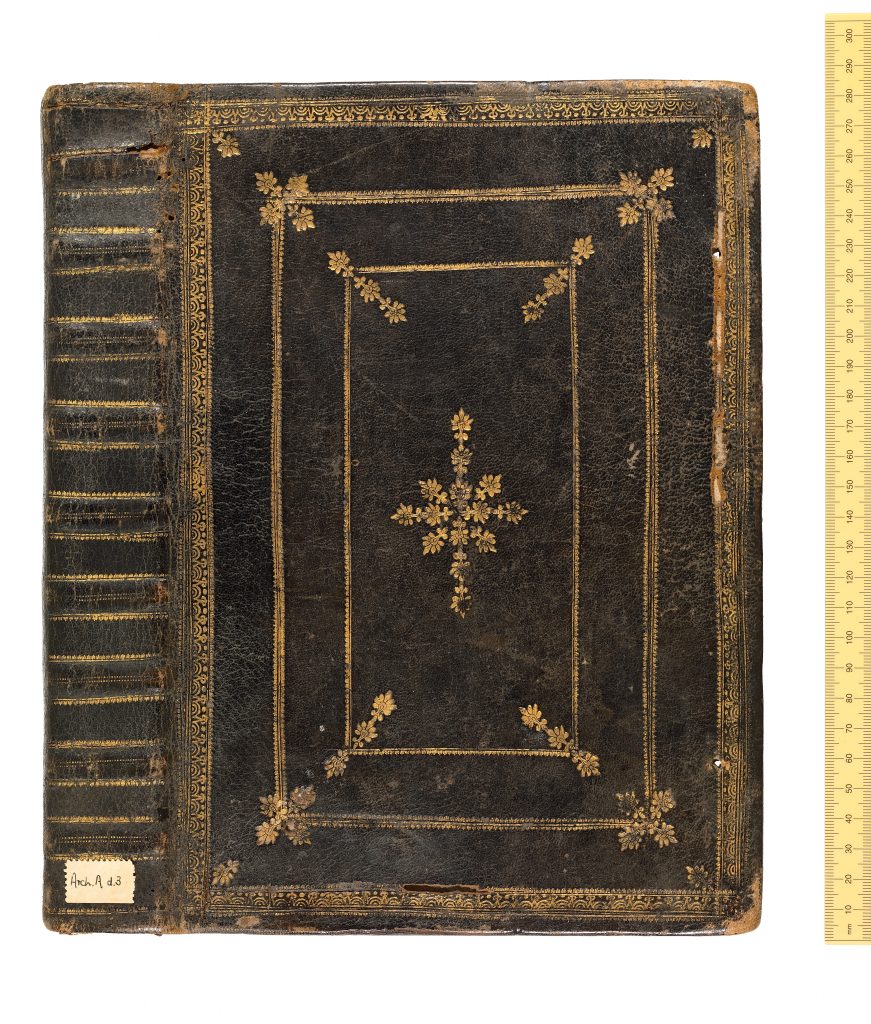

In the first chapter, ‘Cut’, Trettien focuses on the bookwork of ‘harmonies’ produced in Little Gidding by the Ferrar and Collet families. Using cut-and-paste methods to lay out engravings and images from printed Bibles, the Little Gidding authors attempted to synthesise the four gospels of the Bible into cohesive texts. The results join narrative and images across the life of Jesus into strange compositions that aim to be more informative than their constituent parts.

Image Credit: ‘A Harmony of the Gospels, made in 1631 by M.Collet, from cuttings from the Bible’. Shelfmark: Bodleian Library Arch. A d.3. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. Licensed by Digital Bodleian under CC-BY-NC 4.0

Led by Mary Collet, the community grew in renown until their ‘makerspace’ was disrupted by the English Civil War. One harmony was famously borrowed by King Charles I, who annotated the text with corrections only to then stet himself (a great honour!). The King’s harmony was ultimately displayed at the 1939 New York World’s Fair as evidence of British high culture and civilisation — granted high status by the King’s hand and therefore part of the perpetual misrecognition of fragment bookwork.

Trettien describes the communal living at Little Gidding, which gave rise to their proto-feminist bookwork. Through letters and gift editions exchanged among the family, she traces the subsumption of individual willfulness to communal wisdom: ‘Whereas the harmonies were compiled from fragments of printed materials with an eye toward broader circulation amongst elite patrons, these manuscripts function more as semiprivate publications made by and for members of the same disperse family to repair and cement interpersonal relationships’ (64). Although these methods of authorship seem strange today, Trettien argues that the use of scissors, thread and glue tied the Little Gidding harmonies to gendered handiwork: ‘Contrary to later patriarchal scholarship, it was precisely the household’s matriarchal reputation that enabled Little Gidding to accrue cultural agency and political visibility in the seventeenth century’ (35).

Cut/Copy/Paste’s second chapter turns to the long publishing career and patronage of Edward Benlowes. Known for his strange poetic forms and decidedly un-uniform editions, Benlowes nearly dropped out of the bibliographic record — Trettien shows how his memory persisted almost entirely through mockery. His home at Brent Hall became a laboratory where he prepared bespoke presentation volumes (his own print-on-demand) and a personal library that would go on to seed the collections at St. John’s College in Oxford. Unmarried, and assisted by his printer companion Jan Schoren, Benlowes put his life into books.

I confess that it was in this chapter where I most lost the thread: the patronage networks, varying imprints of the same engravings and the minute descriptions of discrepancies between editions of Benlowes’s magnum opus Theophila overwhelmed me. Difficult description, however, is the exact problem that Benlowes tried to address: ‘Benlowes has rendered miscellanity as desirable and, more precisely, his bookwork as a process of desiring: it feeds the composer’s bottomless craving for an ineffable, infinite God whose enormity can be glimpsed in this realm only through endless material recombinance’ (156). This is odd work to enlist a book to do.

Most interestingly, Trettien documents some attempts by Benlowes’s readers to make meaning out of his divine chaos by removing or rearranging engravings within their particular codex. It’s in moments like these, and others like a nineteenth-century expository pamphlet tied to a Little Gidding harmony, that Cut/Copy/Paste shows how different these books were from their modern descendants: ‘Early modern readers often treated their books as containers to hold and store the fragmented remnants of an intensive reading process’ (91). And Trettien argues that it’s partially the difficulty of interpreting what these containers meant that made figures like Benlowes fall out of book history — each of Trettien’s chapters is a ‘historiographic black hole’ (27).

In the final chapter, ‘Paste’, we reach another figure of bibliographic disrepute. A shoemaker turned library agent, John Bagford collected printed ephemera, book waste and exemplars for decades with the intention of using them to publish a comprehensive history of printing. His unusual sources, however, met with disapproval from his upper-class peers. Where Bagford saw his work as salvage, the printed record mostly remembers him as a thief and a destroyer of books. Trettien argues, however, that Bagford’s resourcefulness makes his work more valuable as a bibliographic resource than his contemporaries’ cleaned and crimped curations.

Image Credit: ‘Portrait of John Bagford (1650–1716)’. Shelfmark: Bodleian Library LP 209. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. Licensed by Digital Bodleian under CC-BY-NC 4.0

But going against classification systems has its risks. The albums of Bagford, book-waste pilferer, were themselves pilfered by curators and archivists looking to make other objects whole again. Many of his albums contain rectangular areas, discoloured by glue, where prints were detached so they could be shuffled to some other collection. (This detail reminded me of another open-access book history, Kathryn M. Rudy’s Image, Knife, and Gluepot: Early Assemblage in Manuscript and Print, where Napoleonic curators tore apart unvalued monastic editions to create comprehensive collections of master printers’ work.) And Bagford’s inclusion of manuscript examples along with printed matter put him at odds with categories in modern collections: ‘By imposing an arbitrary division between print and manuscript, the British Museum of the nineteenth century cleaved Bagford’s collection along precisely the lines he was stitching them together […] By removing [page proofs] from their place alongside Bagford’s manuscript drafts and notes, [earlier curators] effectively made Bagford’s writing process appear more inconsistent or haphazard than in fact it was’ (230). Bagford’s un-taxonomic thinking was violated by thinking with taxonomy, and Trettien catalogues each miscalculation and reinterpretation.

I do wish Cut/Copy/Paste had discussed more connections to colonialism and international print culture. Since Trettien sets recognising unrecognised work as the standard, it feels amiss that those two topics don’t get more attention. Early-modern English bookwork remains the focus even when later US and UK readers are considered. This might be because the first two cases mostly concern themselves with ‘homosocial’ bookwork, which sprung from collaborators of similar social backgrounds. But why could the creation and distribution of book materials and prints not be a kind of distributed, asynchronous bookwork?

Cut/Copy/Paste is tied to the digital humanities as Trettien challenges the new-media imaginary of books as static and monolithic — she believes those theories don’t hold up to material study and that they erase the many hands that labour in book production. As part of that challenge, I assume, Trettien has released Cut/Copy/Paste as an open access edition. I have to admit I mistakenly read Cut/Copy/Paste through without looking at the University of Minnesota Press Manifold page. In the running text itself, Trettien does a wonderful job of filling in the blanks of digital experience by describing how navigating these resources should feel at particularly important moments in the book. That descriptive work saves the book’s physical form from just being an off-cast of a fuller digital edition. I saw this effect often as a publishing editor — the ebook was our original, and the print was the copy.

The digital resources that attend Cut/Copy/Paste, however, are a puzzle for the reviewer. By the fact that you’re here reading, I can probably presume you have internet access. But I don’t know what you read for. I think it’s probably safe to say that Cut/Copy/Paste stretches UMN’s Manifold publishing system to breaking point. Compared to most other open-access titles on the platform, which have only the core text, Cut/Copy/Paste has a stonking 440 resources attached to it — images, links, other digital editions, spreadsheets and interactive network visualisations.

The work for Trettien and her collaborators, among them Penny Bee and Zoe Braccia, to assemble these materials must have been herculean. I’m sad to say that many of the interactive resources did not work for me. My computer did not take kindly to the React and Omeka framework used to house the Little Gidding harmonies, for example. Just know that there is a robust network of sources that you can tie in, as you like: Cut/Copy/Paste encourages the kind of thought that is its study.

Although they only appear around the edges of chapters, I found the more recent collagists welcome friends within Cut/Copy/Paste’s pages. The volume opens with paper conservators at the US National Archives, touches on the Little Gidding news clipping and correspondence scrapbooks of Fanny Reed Hammon and nearly closes with Melvin Wolf’s 1967 computer-generated index and thesis. Each of those moments presents a new use for the seventeenth-century case studies, far beyond whatever their original intent might have been. They show the pervasiveness of gendered labour in book and knowledge-making and how future ‘historiographic black holes’ might be made. As Trettien’s Cut/Copy/Paste demonstrates, the lives of books are longer and stranger than we imagine.

- This review first appeared at LSE Review of Books.

- Banner and feature image credit: Image by Sarah Richter from Pixabay.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3zYFI2D

About the reviewer

Sam DiBella – University of Maryland, College Park

Sam DiBella is a PhD student in information studies at the University of Maryland, College Park. He received an MSc with distinction in media studies from LSE. His research focuses on the the changing social value of privacy and anonymity online and the history of information technology. His writing has appeared in Public Books, the International Journal of Communication, Surveillance & Society, ROMChip and Heterotopias, among others. He tweets @prolixpost.