In Underflows: Queer Trans Ecologies and River Justice, Cleo Wölfle Hazard explores the hydrological, cultural and epistemological dynamics of public imaginaries of water and water-related networks through a queer and trans orientation to the world. Covering an impressive swath of ground, this book presents insightful and challenging departures in theory and methodology and is a worthwhile read for ecological scientists and social theorists alike, writes Dani Slabaugh.

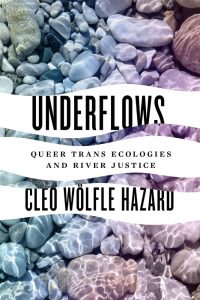

Underflows: Queer Trans Ecologies and River Justice. Cleo Wölfle Hazard. University of Washington Press. 2022.

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

In Underflows, Cleo Wölfle Hazard invites us into the hydrological, cultural and epistemological dynamics of both public imaginaries of water and water-related networks as well as the researcher relationships and ‘straight science’ norms that excise affect, care and kinship from the processes of knowledge production and communication. In doing so, he unpacks the settler-colonial land relations that shape water imaginaries and, by extension, water governance throughout the increasingly drought-stricken, dammed and extracted west coast of the US, tying in critiques and analysis with a queer and trans orientation to the world.

In Underflows, Cleo Wölfle Hazard invites us into the hydrological, cultural and epistemological dynamics of both public imaginaries of water and water-related networks as well as the researcher relationships and ‘straight science’ norms that excise affect, care and kinship from the processes of knowledge production and communication. In doing so, he unpacks the settler-colonial land relations that shape water imaginaries and, by extension, water governance throughout the increasingly drought-stricken, dammed and extracted west coast of the US, tying in critiques and analysis with a queer and trans orientation to the world.

In the first chapter, we are invited into the world of relationship-building and data collection through several case studies, woven through with personal narratives describing the embodied and affective experience of exploring waterways. Hazard shares the visceral sensations of these rivers – the ache of his shoulder as he reaches for fish, the cold of creek water seeping through the knees of his wetsuit – as he acquaints us with both the aquatic life and the adjacent human communities whose concepts of stewardship, property and interspecies relationality impact river flows and collective ecological flourishing.

Image Credit: Photo by Hans Isaacson on Unsplash

The California water wars and their various actors – Indigenous tribes, conservationists, farmers, ranchers, agricultural lobbies and rural settler communities – are unpacked through a set of sometimes conflicting water imaginaries. These imaginaries not only consist of material environmental conditions but also shared schema of property, resource extraction and interconnection. Hazard provides fairly clear examples in the end, but takes some time to get there – the prose winding like one of his beloved tributaries around strongly worded claims regarding social relationships to water.

Tying together critiques from queer theory, feminist science and technology studies (STS) and Indigenous scholarship of science, Chapter Two summarises the shortcomings and critiques of ‘straight science’ rooted in Western, positivistic and affect-starved rationality. Here, Hazard moves on to an interrogation of the role that emotion – in particular grief – plays in the world of university-trained ecologists working in the context of species extinction. Through the story of a salmon-costumed confessional performance art project undertaken by the author and his collaborator and partner July Hazard, we glimpse what even the ‘straight’ scientists working within the disciplinary bounds and normative scripts of their field might gain from ‘queering’ or ‘transing’ science in a way that makes room for affect, care and interspecies kinship. Hazard’s recounting of creative interventions in science communication through performance art – the salmon confessional among them – are delightfully whimsical and thought-provoking.

On the whole, Hazard writes an insightful yet somewhat meandering and – even for myself as a genderqueer LGBTQ academic with a deep appreciation of watershed ecology – challenging narrative, injecting observations and insights from trans and queer lived experience into an otherwise largely theoretical and methodological text. Casual references to queer and trans sexuality and subculture pepper the book in somewhat unexpected and unconventional ways, departing from social mores of straight sexuality. It is clear that Hazard is inviting readers into his and his collaborators’ insights as a trans and queer scientist, rather than attempting to package these in ways that tiptoe around straight readers’ sense of impropriety. Perhaps my, and other readers’, potential discomfort and disorientation is an opportunity to unpack our own internalised biases.

Beyond the serpentine threads of theory and sexuality that – like underflows – appear and disappear without readily apparent or predictable structure, the author makes several broad claims about queer life in framing the context of his theories that deserve some consideration and (loving) critique. The claim that queers gather by rivers is true to an extent, but risks the tone of oversimplified ethnography, despite Hazard’s insider status.

Certainly, the piers of the Lower East Side of New York City and the Albany Bulb in Berkeley, California – two examples described as queer refuges for Hazard and his community of artists and punks – are waterside social spaces well-known in LGBTQ communities. Queer social spaces – especially for those of us with few means – tend to be public spaces where people can express themselves outside of the surveillance, social expectations and occasional harassment of the hetero- and cis-normative mainstream. Such spaces often are industrial waterfronts and parks formed in the undevelopable floodplains of cities, but I would argue (as an inland queer) that there is nothing inherently interconnected about waterfronts and queerness – we are multi-habitat beings as likely to thrive in the desert landscapes of Marfa, Texas, or the waterless grassy expanse of Denver’s Cheeseman Park, as we are by a coastal waterway.

Hazard also makes several references to queer land projects as a category, of which as a queer lover of communes and land projects, I know only three: two in Tennessee (Ida and Short Mountain) and a trans-owned alpaca farm in Southern Colorado. The book offers broad generalisations without transparent reference to which experiences or observations of what land projects in particular have led Hazard to various conclusions and perceptions. This brings to the surface questions of social-scientific rigour. Hazard has undertaken laudable work towards queering the hard science of wildlife ecology, arguably improving that work’s methodological rigour. Yet, Hazard may benefit from further or closer collaboration with fellow queer social scientists that work with ethnography and autoethnography in efforts to bring a queer-trans rigour to his sociological insights. This is not to say that Hazard’s observations are without merit, but merely that they might benefit from further elucidation and specificity.

The book concludes by introducing the concept of the ‘Brown Commons’ – building on theoretical work by late poet and performance artist José Esteban Muñoz. As Hazard articulates, the Brown Commons are not claimed or constructed, but sensed and appreciated. They are an underflow of the everyday, alive with possibility in spite or perhaps because of their damage and disposability in the straight world. The Brown Commons contain the sometimes-accidental contributions of society’s outcasts – sex workers, unhoused people, drug users and LGBTQ communities that gather in public spaces deemed wasteland – as well as the contributions of opportunistic species and the ‘non-productive’ wasteland landscapes themselves.

The Brown Commons offer an articulation of ecological and social interconnection that refuses sanitised imaginaries of industrial waterfronts ‘reclaimed’ through settler-colonial gentrification processes or purity narratives that retrench a wilderness/civilisation dichotomy. They queer – as in unsettle and disrupt – mainstream environmental planning imaginaries and challenge readers to include the theoretical and material interconnections between creative and sometimes dazzlingly self-realised socially outcast groups and – in one example – the PCB-laden fish of Washington’s Duwamish River.

As Hazard describes it, finding the Brown Commons entails a perceptual shift rather than any physical search or changes to the landscape. Such a shift offers opportunities for scientists, planners and land stewards of all kinds to embrace the inherent dignity of not just discarded landscapes but society’s discarded human beings as well. This ‘queer’ move is inherently anti-racist, anti-colonial and anti-capitalist, with the potential to frame land restoration or literal ‘brownfield reclamation’ in ways that contest the settler-colonial and gentrifying gaze of real estate speculators and their bureaucratic allies who may primarily understand ecological projects through their potential to capture increased property value and tax revenues.

While not an easy or quick read, Hazard’s various essays hang together while covering an impressive swath of theoretical ground – from critiques of normative science to articulations of queer theory to the conceptual frames and imaginaries that guide watershed management in drought-stricken California. On the whole, Underflows presents insightful and challenging departures in theory and methodology and is a worthwhile read for ecological scientists and social theorists alike.

- This review first appeared at LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3QfKDkC

About the reviewer

Dani Slabaugh – University of Colorado, Denver

Dani Slabaugh, MLA (she/they) is a PhD student in the Geography Planning and Design program at the University of Colorado, Denver. Their interests and passions revolve around non-speculative forms of land tenure, social movements, and climate justice. She roots her work in feminist, anti-racist and anti-colonial frameworks, engaging in research in order to contribute towards a more just, resilient, and thriving world. (my website is here: https://danimarieportfolio.wordpress.com/)