In The Anthropocene in Global Media: Neutralizing the Risk, editor Leslie Sklair brings together contributors to explore how the Anthropocene is reported in mass media globally. Full of rich empirical details and insightful discussions, this enlightening book deserves the attention of anyone interested in evolving public discourses of the Anthropocene, recommends Sibo Chen.

The Anthropocene in Global Media: Neutralizing the Risk. Leslie Sklair (ed.). Routledge. 2021.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

Since the birth of environmental communication, how media around the world covers climate change has been a major research focus of this interdisciplinary field, with projects such as the Media and Climate Change Observatory offering regular summaries and analyses of shifting public opinion. By comparison, only in recent years has the concept of the Anthropocene begun to gain traction among environmental communication scholars. In recognition of this research gap, The Anthropocene in Global Media aims to offer ‘the first systematic study of how the ‘‘Anthropocene’’ is reported in mass media globally’ (i). Judging from the book’s rich empirical details and insightful discussions, it has completed the task in admirable ways.

The crux of the book’s analysis concerns the emergence of three main narratives about the Anthropocene found in global media coverage: ‘neutralizing’; ‘good Anthropocene’; and ‘radical change’. The combination of ‘neutralizing’ and ‘good Anthropocene’ offers a reassurance storyline downplaying the Anthropocene’s negative impacts. Although coverage following the ‘radical change’ narrative challenges this by framing the Anthropocene as a genuine existential threat to human beings, such alarmist discourses are utterly dwarfed by those considering the Anthropocene as a challenge to be overcome by technological advancements or as an ‘inevitable process’ not worth worrying about. The book’s subtitle ‘neutralizing the risk’ accurately captures the gist of these research findings.

The book elaborates global media’s neutralisation of climate change risks in three parts. In Part One, ‘The Anthropocene and Media’, editor Leslie Sklair introduces the Anthropocene Media Project (AMP), which the book’s empirical findings are based upon. He argues that seemingly innocuous linguistic choices have significant implications for how the general public perceives a rising global average temperature. By stressing human impacts on the Earth system, the term ‘Anthropocene’ is more politically provocative than ‘global warming’ and ‘climate change’. The perceived risks of the Anthropocene are open to many interpretations. How these interpretations compete with each other within the global media landscape informs AMP’s research questions.

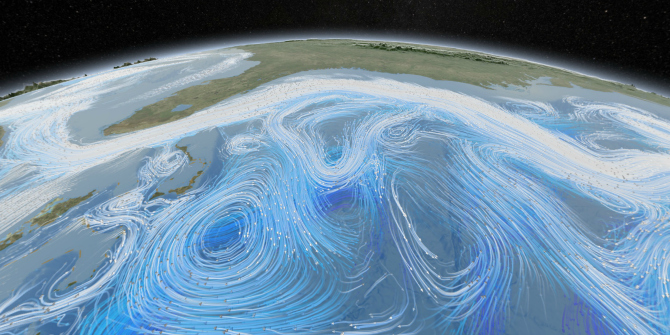

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Part One’s review of AMP’s methodological details highlights another distinctive character of the book: namely that all of its empirical chapters follow the same methodological framework. Such consistency not only strengthens the comparative analysis of how media coverage of the Anthropocene varies across geographical regions, but also makes the book’s narrative easy to follow.

Part Two, ‘Media Coverage of the Anthropocene: A Global Survey’, consists of nine chapters, with each attending to how media outlets in one geographic region (Africa, North America, North Asia, etc) frame the coming of the Anthropocene and its socio-economic impacts. These chapters collectively reveal two notable commonalities shared by global Anthropocene coverage.

First, instead of uncritically replicating Euro-centric and US-centric narratives, media in many parts of the world—especially the Global South—have ‘provincialized’ the Anthropocene by adopting ethnic, national and regional perspectives into their narratives. In Africa (Chapter Three by Meryl McQueen and Sklair), for instance, although the continent’s overall media’s references to the Anthropocene are relatively low in comparison to developed regions, there is dense Anthropocene coverage in countries such as Liberia and Zimbabwe, which pay special attention to climate injustice issues that are intensified by the Anthropocene. Meanwhile, in the Middle East (Chapter Ten by Baran Alp Uncu and Ramzi Darouiche), the fossil fuel sector’s significant influence on regional political economy creates structural barriers for in-depth media discussions on the Anthropocene and related environmental challenges.

Second, there is an ongoing discursive struggle between news stories addressing the Anthropocene as a neutral, scientific concept and those emphasising its deep connection with social theory. While the former cluster of stories depoliticises the Anthropocene and reproduces the reassurance storyline, the latter politicises the concept and anticipates further uneven social transformation of the planet by human behaviours.

How to amplify the political discussions around the Anthropocene is a shared concern among authors in Part Two (for example, Chapter Five’s analysis of Latin American and Caribbean media by Viviane Riegel, Sofia Ávila and Jerico Fiestas-Flores as well as Chapter Nine’s analysis of Western Europe by Boris Holzer and Sklair). As shown in their analysis, decolonisation presents a promising topic for prompting critical public conversations on the Anthropocene and how to mitigate the planetary emergency associated with it. Although the surveyed media texts rarely discuss issues like colonialism and imperialism directly, there are many indirect critiques recognising capitalist accumulation as the root cause of climate change. According to Sklair, the presence of such critiques in both developing and developed countries ‘point to the ways in which the concept [of the Anthropocene] might be liberated from its white, male, Eurocentric roots’ (30).

Part Three, ‘From the Anthropocene to the Anthropo-scene’, concludes the book with three summative chapters reiterating the urgent need for more scholarly and public discussions on the Anthropocene. For this purpose, creative arts may offer a surprising solution. An unexpected finding from the book’s survey of Anthropocene coverage worldwide is the relatively dense media coverage of Anthropocene-related creative arts. Representations of the Anthropocene can be found in almost all arts genres (exhibition, photography, music, etc). The depth and diversity of ideas and expressions embedded in these creative works raise an interesting question for future research: what communication strategies can environmental professionals and scholars learn from artists?

The Anthropocene in Global Media is a brilliant book that reveals competing media narratives on how human civilisation shall address Anthropogenic changes to the Earth’s climate. As the book convincingly argues:

consciously or unconsciously, the mass media and many of the scientists and commentators they report have generally neutralized the risks of the Anthropocene, either by failing to mention them at all or by turning them into opportunities for human ingenuity and profit (252).

While this main conclusion may not come as a surprise to readers familiar with the current impasse of international climate negotiations, the book’s strength lies in its rich empirical details, especially the explorative analyses of Anthropocene coverage in the Global South. Admittedly, linguistic barriers mean that the book has probably neglected many news stories on the Anthropocene published in minority and Indigenous languages, but its rigorous and consistent examination of 4000+ news items still provides an impressive overview of hegemonic and counter-hegemonic forces underlying the Anthropocene’s media representations in different geographical regions. In short, this enlightening book deserves the attention of anyone interested in evolving public discourses of the Anthropocene.

- This article originally appeared at LSE Review of Books.

- Featured image by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3rKAyB3

About the reviewer

Sibo Chen – Ryerson University

Dr Sibo Chen is an Assistant Professor at Ryerson University’s School of Professional Communication. His research areas of interest include energy-society relations, environmental communication, critical discourse analysis, communication and identity, and instructional communication.