In new research, Pauline Grosjean, Federico Masera, and Hasin Yousaf look into how Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign affected police behavior toward Black Americans. They find that that Black drivers were 5.7 percent more likely to be stopped by police after a Trump rally, and that this effect happens immediately after the rally, is specific to Black drivers, lasts for up to 60 days and is not justified by changes in driver behavior.

The United States witnessed a resurgence of racial and ethnic turmoil and tensions during Donald Trump’s presidency. This may have culminated in the violent protests and intrusion in the Capitol of Trump’s supporters on January 6th, 2020, but, as we argue, it was seeded in Trump’s first presidential campaign in 2015/2016.

Some point directly to Trump’s inflammatory leadership as the reason for this turmoil. In the New York Times, just after the January 6th Capitol attack, historian Timothy Snyder, for example, wrote that Trump’s inflammatory racial rhetoric comforted the views of “supporters convinced that the enemy was at home”.

While Trump’s campaign did not explicitly disparage African Americans, numerous political science and law studies show how certain speech can carry a hidden message only understood by a targeted subgroup and that activates threatening stereotypes — a phenomenon known as the “dog-whistle effect”. As former Vice-President, now President, Joe Biden put it in during the presidential election debate with Donald Trump, on 30 September 2020: “This is a president who has used everything as a dog whistle to try to generate racist hatred, racist division.” Put plainly, this would imply that by invoking threatening outgroups of drug dealers, criminals and “rapists”, Trump was, in fact, stirring deep-seated racial divisions against Black Americans.

How Trump’s rhetoric affected police behavior towards Black Americans

We study how Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign has affected the expression of racial prejudice and discrimination against Black Americans in one of its most fundamental and violent dimensions: police behavior. Although fatal encounters between police officers and black civilians have tended to capture more of the media’s attention, over-enforcement of minor infractions and the kind of unjustified stops by the police that we looked at it in our study provide a daily and generalized expression of discrimination against minorities. According to Bureau of Justice Statistics, 8.6 percent of US residents aged 16 and over, more than 20 million people, were pulled over by the police during a traffic stop in 2015. Our own estimates suggest that, at baseline, Black drivers overrepresented by a factor of two compared to their proportion in the population.

To analyze the effects of Trump’s campaign on the expression of racial prejudice and discrimination against Black Americans, we use data on 35 million vehicle stops by the police, including in 141 counties where Trump held a campaign rally as a candidate for the Republican nomination or the presidency.

Ticket” (CC BY 2.0) by chucknado

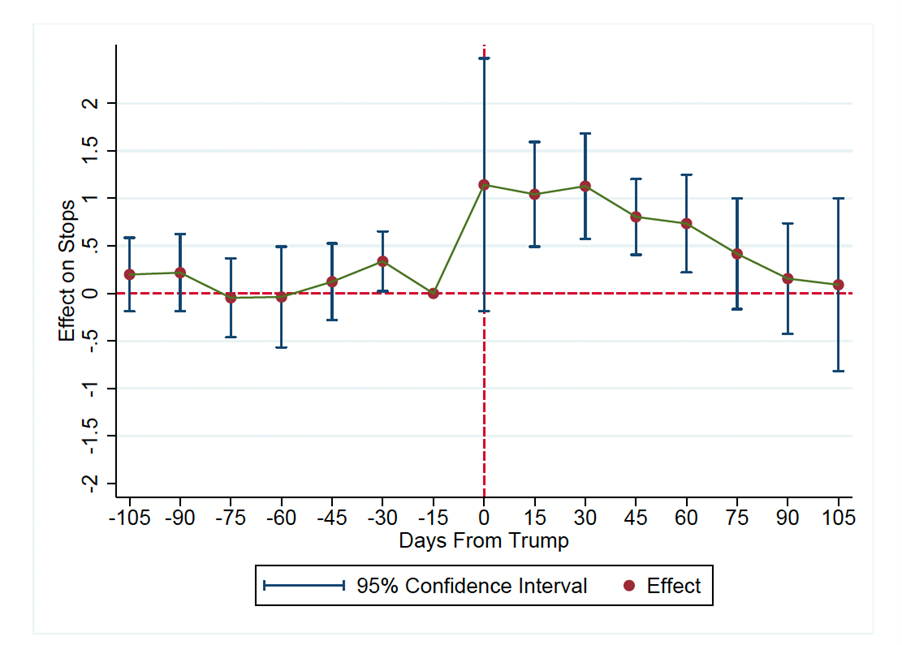

We find evidence that Trump rallies increased the probability of a Black stop by 1.1 percentage points on average in the 30 days following a rally, a 5.7 percent increase. The effect is immediate and lasts for up to 60 days (see Figure 1). We show that the results are specific to Black drivers and do not concern other minority drivers, including Hispanics. The results are also specific to Trump rallies: we find no effect on police stops of rallies held by either the Democratic contender to the presidency in 2016, Hillary Clinton, the other leading Republican opponent, Ted Cruz.

Figure 1 – Impact of Trump Rallies on the Probability of a Black Stop

Trump’s remarks changed the way police behaved towards Black Americans

Using stop-level information on collisions and speed radars as well as additional evidence from crash and fatality data, we find no evidence for a change in the racial composition of drivers or in driver behavior. These results suggest that the effect of Trump rallies is due to a change in law enforcement behavior.

At first, these results may seem odd given that Trump’s inflammatory remarks during his campaign were openly directed against Hispanics and Muslims, not Black Americans. We interpret this result as the manifestation of the dog-whistle effect, whereby coded language appeals to deep-seated stereotypes of groups that are perceived as threatening. In other words, individuals prejudiced against Black Americans may see in Trump’s speeches a confirmation of their views or an implicit authorization to act upon them.

We provide two pieces of empirical evidence that support our interpretation. Firstly, we show that the effect of Trump’s rallies is much larger in areas in areas that score higher on present-day measures of racial resentment, those that experienced more racial violence during the Jim Crow era, and in former slave-holding counties; as well as for police whose behavior was more consistent with racial discrimination before a rally. By contrast, we do not find any difference in the effect along other dimensions, including income, education, political affiliation, or a recent increase in imports from China.

Secondly, we show that officers whose behavior was more consistent with racial discrimination before a rally are particularly triggered by speeches that refer more often to race, either explicitly, or implicitly, for example using euphemisms understood by some as references to a racial group (“urban”, “thug”) or references to topics that can trigger some negative racial stereotypes. By contrast, speeches that refer more often to the economy, international trade, or political corruption do not generate these effects.

Rhetoric can have real consequences

Our research shows how the rhetoric used by highly visible individuals can have tangible consequences. Even when Donald Trump was not holding an elected position and many polls placed his presidential victory as unlikely, we show that his rallies influenced police behavior towards Black drivers. This is particularly striking given that the explicit xenophobic views of Trump were almost completely targeted towards Hispanics and Muslims. This result contributes to the ongoing debate regarding the value and cost of freedom of speech.

These findings are also of significant policy relevance because of the many indirect effects that racially targeted behavior by police may have on minorities. For example, historical discrimination and violence against Black people is still associated, to this day, with lower voter registration by Black voters.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Inflammatory Political Campaigns and Racial Bias in Policing’, in The Quarterly Journal of Economics.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3EBxDTU