Since Donald Trump’s defeat in the 2020 presidential election, many commentators have attributed his election loss to his poor handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. In new research, Carlos Algara, Sharif Amlani, Sam Collitt, Isaac Hale, and Sara Kazemian find that this is not the whole story. Comparing changes in Trump’s vote share with COVID-19 mortality rates, they find that Trump performed better in places more badly affected by the pandemic. They argue that Trump’s election-campaign messaging about the negative economic impact of lockdowns and other pandemic-related restrictions likely drove the increased voter support for him in the worst affected areas.

Conventional wisdom holds that the COVID-19 pandemic directly and seriously damaged Donald Trump’s reelection effort in 2020. The depth of the crisis during 2020 is hard to overstate: from the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in January 2020 to Election Day in November, the United States experienced over 9,400,000 cases and 232,000 deaths. Prior to the election, public opinion surveys showed that a majority of Americans disapproved of Trump’s handling of the pandemic. Even Trump’s own aides told The Washington Post in an election post-mortem that Trump’s mismanagement of the virus was the primary cause of his loss to Biden.

Despite the 2020 consensus that COVID-19 directly hurt Trump’s reelection bid, subsequent investigations have yielded mixed results. While some studies have found that COVID-19 hurt Trump’s reelection, other investigations found that Trump actually performed better in states and counties with higher COVID-19 mortality rates. In new research, we find that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected voter behavior and attitudes during the 2020 US presidential election – but not in line with conventional wisdom.

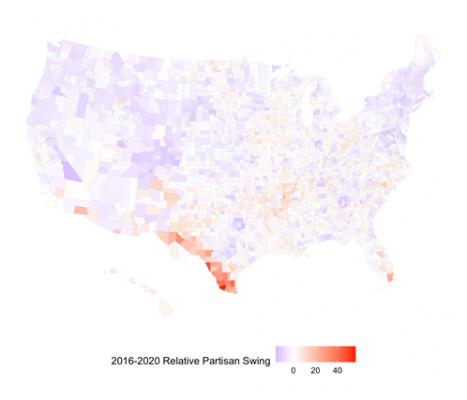

Figure 1 – Change in County-Level Support for President Trump During the 2020 Election

Trump’s vote share improved in counties with rapid COVID-19 onset

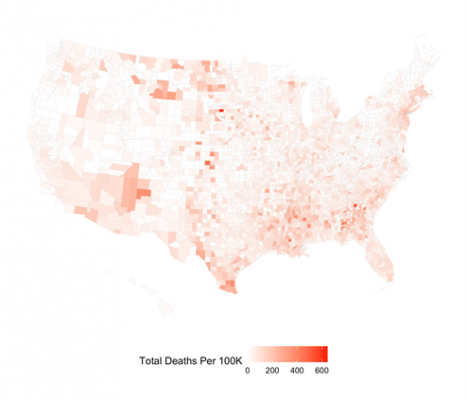

At the county level, we find that higher COVID-19 severity was associated with greater Trump support in 2020. We generate short-term and long-term measures of COVID-19 severity using county-level data from the New York Times, which tracks the cumulative number of confirmed deaths and cases from the first confirmed case on January 21, 2020, in Snohomish County, Washington until Election Day on November 3, 2020. The results are striking: Trump improved on his 2016 vote share by nearly 3 percent in counties with the most rapid short-term increase in COVID-19 deaths the week prior to Election Day compared to similar counties with no COVID-19 surge.

Our long-term measure similarly shows that Trump gained in the worst-hit counties, where his vote share improved by roughly half a percentage point in the counties with the most cumulative COVID-19 deaths. While these gains may appear modest, it is important to note that these county-level gains due to COVID-19 deaths are roughly on par with President Trump’s losing statewide margins in Arizona (0.31 percent), Georgia (0.24 percent), and the tipping-point state of Wisconsin (0.63 percent). After accounting for all standard predictors of President Trump’s county-level performance, it appears that his electoral gains from COVID-19 death severity may have kept the statewide margin in these critical battleground states close.

Figure 2 – Cumulative Deaths from COVID-19, by County

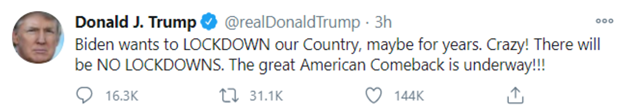

These county-level results present a puzzle: how could Trump have electorally benefited from COVID-19 when the public gave him poor marks for his handling of the pandemic? The answer, we argue, can be seen in the rhetoric of the Trump campaign itself, which emphasized the economic impacts of COVID-19 restrictions. As early as the spring of 2020, Trump tweeted that “WE CANNOT LET THE CURE BE WORSE THAN THE PROBLEM ITSELF” and in response to state-imposed stay-at-home orders tweeted “LIBERATE MINNESOTA!,” “LIBERATE MICHIGAN!,” and “LIBERATE VIRGINIA.” During a town hall, President Trump commented that “you’re going to lose more people by putting a country into a massive recession or depression,” suggesting that a Democratic victory would mean more economic shutdowns and more prolonged restrictions that would close large portions of the American economy.

Other GOP officials were quick to align with Trump’s messaging. In April 2020, Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick suggested that grandparents should be willing to risk death in order to end restrictions in the state. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis said, “the cost of the lockdowns are borne by working-class people. The benefit is to the Zoom-class, the upper-income people who can work from home. Not everyone can do that. You have to go out.”

Photo by Cole Freeman on Unsplash

In the week leading up to the election, Trump’s COVID-19 messaging was firmly focused on the economic cost of restrictions, as reflected in Tweets like, “Biden wants to LOCKDOWN our Country, maybe for years. Crazy! There will be NO LOCKDOWNS. The great American Comeback is underway!!!” and “The Biden Lockdown will mean no school, no graduations, no weddings, no Thanksgiving, no Christmas, no Fourth of July.”

A November 1, 2020 Tweet from Trump, Appealing to Voters Concerned About the Economic Impacts of Lockdowns

Concerns about lockdowns drove up support for Trump, but not enough for him to win

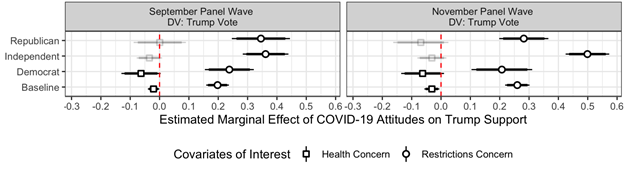

This messaging from Trump and other GOP leaders was effective: at the individual level, we show that concern about the negative economic impact of pandemic-related restrictions (e.g., lockdowns, mask mandates, business closures) was associated with higher Trump support while concern about public health was largely uncorrelated with Trump support. This dynamic manifested among Democrats, Republicans, and independent voters, as seen in Figure 3 below. The marginal effect of health concerns and restrictions concerns on a voter’s likelihood of voting for Trump are shown for each partisan group and for all voters (the “baseline” category). Values greater than zero indicate a positive relationship, below zero a negative relationship, and estimates in gray are not statistically significant. The left panel shows survey data from September 2020 while the right panel shows survey data from November 2020 (immediately preceding the election).

Figure 3 – Relationship Between Public Health Concern/Restrictions Concern & Political Support for President Trump

These results provide a potential mechanism that explains why we find that President Trump gained in areas hardest hit by COVID-19 deaths. Fears about the economic costs of lockdown restrictions among voters in these areas drove up their support for President Trump. In other words, we find support for the hypothesis that President Trump’s campaign message that COVID-19 restrictions would hurt the economy was a viable strategy in the face of a challenging electoral landscape.

Despite our findings, the greater individual-level effect of restrictions concerns was not enough to swing the election to Trump. Approximately 60 percent of voters nationwide were more concerned about restrictions being lifted too quickly – in alignment with a public health framework. While President Trump gained among some members of the public by priming economic effects, these primes were ultimately not sufficient to carry him to victory, as only 40 percent of the public across both survey waves were concerned that restrictions would not be lifted quickly enough. Moreover, the proposition that restrictions were being lifted too slowly enjoyed substantially less than majority support among independent partisans, a key voting bloc during President Trump’s ultimately unsuccessful 2020 re-election bid.

Our study raises important questions about presidential accountability during national crises. Voters nationwide did punish Trump for his perceived mishandling of COVID-19 – in line with popular media narratives during and following the election. However, the effects of COVID-19 at both the individual and aggregate levels are much more dynamic. The counties worst hit by the pandemic were more likely to support Trump, and our results suggest that the cause was a county-level increase in the importance of economic concerns related to pandemic restrictions – which Trump and other Republicans highlighted in the 2020 campaign. While many observers assumed that widely reported public dissatisfaction with Trump’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that he would be severely punished by voters in 2020, our results suggest that we should be cautious in the face of such predictions.

- This article is based on the paper, “Nail in the Coffin or Lifeline? Evaluating the Electoral Impact of COVID-19 on President Trump in the 2020 Election” in Political Behavior.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3fljy2x