For much of the global pandemic, authorities have talked about the “war on covid”. In new research, Jessica Blankshain, David Glick, and Danielle Lupton examine the effectiveness of such war rhetoric on public attitudes about the pandemic, specifically, on respect for and what motivates essential workers, and towards COVID-19 related behavioral restrictions. They find that using the war metaphor did little to shift public attitudes on pandemic restrictions, and that it increased people’s perceptions that essential workers are motivated by compensation rather than service.

For much of the global pandemic, authorities have talked about the “war on covid”. In new research, Jessica Blankshain, David Glick, and Danielle Lupton examine the effectiveness of such war rhetoric on public attitudes about the pandemic, specifically, on respect for and what motivates essential workers, and towards COVID-19 related behavioral restrictions. They find that using the war metaphor did little to shift public attitudes on pandemic restrictions, and that it increased people’s perceptions that essential workers are motivated by compensation rather than service.

From the beginning of the global pandemic in the spring of 2020, politicians, public health officials, the media, and others have referred to the “war on covid.” It’s easy to understand the appeal of such rhetoric. Over the past fifty years, the United States has declared war on, among other things, terror, drugs, poverty, and cancer. Those who use the covid war metaphor presumably believe that this language helps to rally the public to change behaviors or support certain policies. But recent research suggests that at least during the COVID-19 pandemic, this familiar political rhetoric may have done little to increase support for behavioral restrictions or for essential workers and may have even backfired.

How do people react to war as a COVID-19 metaphor?

In new research we find that using the war metaphor to discuss COVID-19 does little to affect public attitudes about the pandemic, at least in the current polarized political environment. In a 2020 survey experiment using a Qualtrics panel of about 1500 participants across the United States—selected to be nationally representative on age, education, race, and sex—we prompted respondents to consider hypothetical new legislation being proposed to support essential workers. Several such proposals were under consideration in the US Congress at that time. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of three conditions. In the baseline condition, we simply referred to some supporting such legislation because essential workers “deserve our unwavering support.” In the “war metaphor” condition, we referred to essential workers as “soldiers on the frontlines of a war against a deadly enemy.” In a final “non-militarized crisis” condition, we referred to essential workers as “brave heroes in this public health emergency.” The two treatment conditions were included to allow us to separate the effects of the war metaphor from a non-militarized invocation of crisis.

We then solicited views on several pandemic-related policies and attitudes. We asked about obligations to modify individual behavior to avoid spreading COVID-19. In addition to asking about support for policies that gave targeted financial support to essential workers, we asked about the acceptability of essential workers being exposed to higher risks for the sake of society. It’s possible that use of the war metaphor might make the public view essential workers as more expendable—that harm to essential workers is tragic but part of the necessary costs of war. Given the high-level of societal confidence in the military in the United States, language that compares essential workers to soldiers may also elevate the social status of essential workers. To test this effect, we asked about perceptions of essential worker motivation—more motivated by service to others or by compensation—and about respect for essential workers.

Using the war metaphor did not shift public attitudes

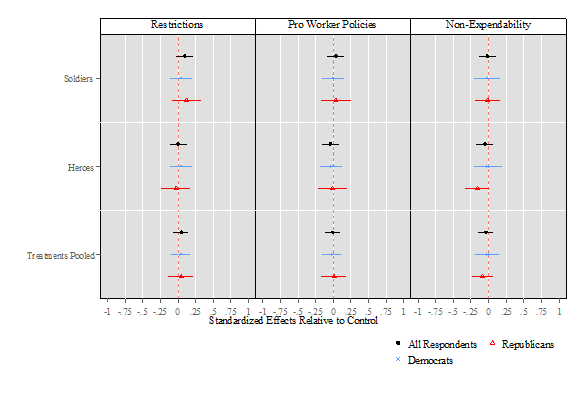

On issues that quickly developed strong partisan divides, like the imposition of pandemic restrictions, the use of the war metaphor (or of a non-militarized crisis) did little to shift public attitudes. In the control condition, compared to Democrats, Republicans in our sample were less supportive of behavioral restrictions, less supportive of targeted policies to support essential workers, and more likely to view the risks essential workers take as acceptable and not the responsibility of their employers. While there were differences in base level views, neither rhetorical treatment significantly shifted attitudes on these measures, either overall or for members of either party (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Effects of Rhetorical Treatments on Support for Policy and Behavior Change

Effects of rhetorical treatments on views about covid policies. Positive estimates indicate increased support for limiting individual behavior to reduce spread, support for targeted benefits, and opposition to notion that some have to incur risks for society

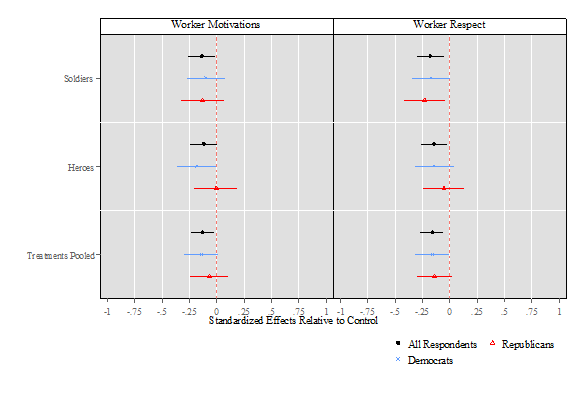

At the same time, however, our research reveals that the war metaphor could have some real downsides, at least in some circumstances. Our survey found that on issues with less of an underlying partisan divide —views of essential workers themselves—war and emergency language had the opposite effect than we anticipated (as shown in Figure 2). Both the war metaphor and the non-militarized crisis invocation increased perceptions that essential workers are motivated by compensation relative to service to others, and decreased respect for them.

Figure 2 – Effects of Rhetorical Treatments on Views of Essential Workers

Effects of rhetoric treatments on views of essential workers’ motivations and respect for essential workers. Negative effects indicate respondents viewed workers as more motivated by compensation and had less respect for them.

Overall, our research suggests that those using the war metaphor to rally the public in support of pandemic response are unlikely to succeed and may do more harm than good. Even such a stark rhetorical device does little to cut through existing partisan cleavages. And rather than leveling the playing field, the war metaphor may serve to reinforce the military’s privileged position as the pinnacle of service. Of course, some may use the war metaphor for less noble ends—it may also allow leaders to bolster their own popularity or avoid oversight and accountability during a crisis.

- Featured image: “Lotte New York Palace Displays Stay Safe During COVID19 Quarantine New York City” by Anthony Quintano is licensed under CC BY 2.0

- This article is based on the paper ‘War Metaphors (What Are They Good For?): Militarized Rhetoric and Attitudes Toward Essential Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic’, in American Politics Research.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and do not represent the official views or positions of their employers, nor of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3Tl64ld

1 Comments