Though passed by Congress in 2010, the Affordable Care Act, also known as ‘Obamacare’ only came into place towards the end of 2013. The initial months of the program have been characterized by a litany of IT failures for the healthcare.gov website, and concern over gaps in health insurance coverage. Daniel Béland, Philip Rocco, and Alex Waddan write that while the debate over Obamacare is no longer about its repeal, its supporters and opponents still face battles over how it is instituted. They argue that Republican states are using their legislative capacity to thwart the law, which may give Democrats the opportunity to place blame on them for coverage gaps.

Though passed by Congress in 2010, the Affordable Care Act, also known as ‘Obamacare’ only came into place towards the end of 2013. The initial months of the program have been characterized by a litany of IT failures for the healthcare.gov website, and concern over gaps in health insurance coverage. Daniel Béland, Philip Rocco, and Alex Waddan write that while the debate over Obamacare is no longer about its repeal, its supporters and opponents still face battles over how it is instituted. They argue that Republican states are using their legislative capacity to thwart the law, which may give Democrats the opportunity to place blame on them for coverage gaps.

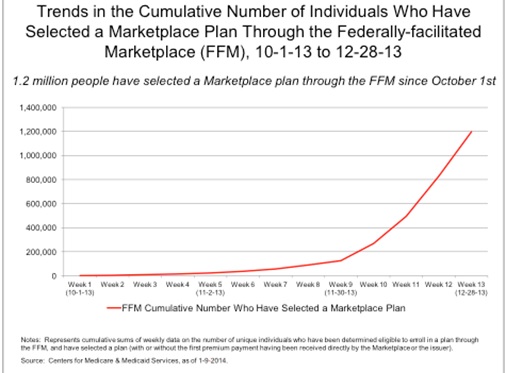

Since it took off in 2010, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has been flying through turbulent skies. In the past three years, House Republicans have launched 47 attempts to repeal the law, and have plans now to offer alternatives to it. The rollout of both federal and state online health-insurance marketplaces was widely perceived as problematic. And in the states, many Republican officials have actively attempted to obstruct the law, all while enrollment in federally facilitated marketplace plans has steadily increased (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Increasing Enrollment in Federally Facilitated Plans

In this context, ideological closure has reigned supreme. Supporters of the law believe it will emerge through these minefields unscathed. Opponents believe that the botched early rollout will ultimately doom the law, especially if a Republican presidential candidate emerges victorious in 2016. Both of these viewpoints, however, misapprehend the larger set of challenges and opportunities that policy elites on both sides of the aisle are facing.

As our research shows, the battle over the ACA is no longer about repeal. Rather, supporters and opponents of reform are now using the ACA’s institutional terrain as a site for new political contests, such as renegotiating the administration of Medicaid and establishing new insurance market regulations. So the relevant question is: how will the ACA evolve over time? The answer to this question depends on how the law’s supporters respond and adapt to outstanding policy problems in a context of institutional fragmentation, demands for high-quality service to be delivered under budget and without error, and a polarized environment in Washington, which is making normal updates to the ACA (key to the early life of public policies) difficult to ratify, and sloughing off critical policy decisions to states with partisan monopolies.

The importance of institutional fragmentation

Thus far, the implementation of ACA has taken place in a context of political conflict similar to the one that led to its enactment in March 2010. But what makes the divide between Democrats and Republicans so influential as far as implementation is concerned is the law’s intergovernmental structure, which allocates key policy authority to both federal and state actors. From this perspective, the law has strongly complicated the rolling out of health-insurance exchanges as well as the expansion of Medicaid benefits by permitting state political leaders opposed to the law to refuse to cooperate in its rollout. The June 2012 Supreme Court decision allowing states to opt out of this expansion without penalty also facilitated institutional opposition to ACA implementation in Republican-controlled states.

Although states have strong fiscal incentives to participate in this expansion, Republican opposition to the ACA is so strong in most GOP-controlled states that opting-out of Medicaid expansion and state-controlled marketplaces became the dominant policy option, with a few notable exceptions. Because of the law’s design, opt-outs could be highly visible political decisions, taken in legislatures and in governor’s offices. In contrast, the institutional design of the ACA regulatory reforms affecting insurance markets have not been as controversial and politically contentious, for the most part. This is the case because, considering their distinct institutional design, these regulatory changes have a lower level of political salience, which makes them less likely to become central elements of the political showoff over ACA than the health insurance exchanges and the proposed Medicaid expansion (on this see our forthcoming article in Health Policy).

As the law continues to evolve, governors and federal administrators in support of the law will attempt to find ways to remove core implementation issues from direct political disputes. By contrast, opponents who still see cutting down “Obamacare” as a winning issue will try to make large political fights out of mundane administrative issues. As long as the ACA remains a strong campaign issue for Republicans, Democrats may seek a quieter, more obscure path to promoting the ACA’s implementation across jurisdictional boundaries, working with state Medicaid directors and insurance commissioners to forge “middle-road” solutions to improve the quality and cost of health coverage.

The evolving challenges of service delivery

Whereas institutional fragmentation and polarization may seem like the same old story of contemporary American politics, there is much that is new with the ACA, and much that is new can add to policy turbulence. The recent rollout of the federal website healthcare.gov was widely criticized, with blame frequently targeted on incompetent bureaucrats. However, our ongoing research suggests that three deeper institutional and market patterns are responsible for the problems that emerged and the degree of negativity that those problems generated.

First, public expectations of what service delivery should be like have increased, and there is little tolerance for policy implementation through trial and error. Recent polling data suggest that now, more than ever, citizens demand that government provide programs that contain client-customized performance, which healthcare.gov attempted to achieve.

Second, demand for high quality service comes against a background of public sector austerity that has made it more difficult for government to function effectively at many levels, but especially when the task at hand is to oversee major new public policy innovation. In addition, the use of private sector providers, especially on the IT side, exaggerates the difficulty of effective oversight. These issues were exacerbated with regard to the ACA by the manner in which much of the planning for roll out of the exchanges was done under the political radar with inadequate resources.

Third, bureaucrats increasingly operate in a culture that demands performance and damns apparent mistakes, especially when the political stakes are high and opponents of policy initiatives are champing at the bit in anticipation of any implementation problems that they might highlight. One consequence of this pattern is to make those bureaucrats even more unwilling to admit to problems when they emerge. Certainly with the ACA, there is evidence that there was an unwillingness to acknowledge the evidence of likely problems with the federal exchange marketplace being designed for those states who had chosen not to develop their own exchange.

The direction the ACA takes in the future will have much to do with how government responds to these patterns. If budgets are increasingly constrained, and if tolerance for error remains low, the HHS may have little slack to do the kind of innovations necessary to keep pace with increasing client demands.

The persistence of polarization and a two-sided policy regime in the States

Looking ahead, persistent polarization in Congress and an increasingly cash-strapped federal bureaucracy make it difficult to see how Washington alone can be responsive to problems of health-care quality, cost and accessibility. What’s more, there may be real limits to what Washington can do about policy problems like the “coverage gap” caused by many states’ failure to expand the Medicaid program. In short, the future of ACA may depend on state governments’ ability to respond to consumer demands about the cost and quality of coverage.

Our working paper on state-level health insurance policy suggests, however, that the ACA’s evolution may be heavily bifurcated. When we look at the level of state legislative activity and characteristics of state legislative enactments, we see two divergent policy regimes. States led by the Democratic Party are significantly more likely to become “co-producers” of policy, investing in legislative activity on health reform and the development of policy expertise, while states controlled by Republicans are using their legislative capacity to stir dissent and to thwart the core goals of the law. For instance, whereas California is currently pursuing legislative and ballot initiatives to clamp down on unreasonable rate increases and to control prices, states like Missouri are passing bills like the “Big Government Get Off My Back Act”, which do much to assuage political opposition to the ACA but little to address the concerns of consumers in the marketplace.

For the near term, the divergence does not appear to be letting up, especially given political polarization in the states. This suggests that the “diffusion” of health policies from Democratic to Republican states will stall out, especially if Republican states can continue to credibly claim that the problems with the ACA are the fault of the federal government, not the states. However, as enrollment in the exchanges ticks up, and more citizens find themselves in the coverage gap, Democrats may be able to successfully pin the blame on recalcitrant governors and state legislatures for failing to take up the reins on issues like the accessibility, cost, and quality of health coverage. Such a campaign would remain challenging to coordinate across so many states, but if Democrats hope to achieve policy convergence, it would be a challenge well worth accepting.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1bhCQID

_________________________________________

Daniel Béland – University of Saskatchewan

Daniel Béland – University of Saskatchewan

Daniel Béland is Canada Research Chair in Public Policy and a professor at the Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy, University of Saskatchewan campus. He has published ten books, including The Politics of Policy Change (with Alex Waddan) and What Is Social Policy? Understanding the Welfare State.

_

Philip Rocco – University of California, Berkeley

Philip Rocco – University of California, Berkeley

Philip Rocco is a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of California, Berkeley. He is working on a dissertation entitled Forging a Complex Republic: Political Conflict and the Statutory Origins of American Intergovernmental Relations, 1945–2012. His work has been featured in The Journal of Public Policy, Publius, and Health Policy.

_

Alex Waddan – University of Leicester

Alex Waddan – University of Leicester

Alex Waddan is a senior lecturer at the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom. He is the author of The Politics of Policy Change (with Daniel Béland), and The Politics of Social Welfare.