Cynthia Golembeski provides an overview of the current state of the US cash bail system, writing that bail policies and practices are expensive, unjust to poor people and people of color, and may conflict with the US Constitution and Civil Rights Act and international human rights law. She discusses bail-related activism including community bail funds, as well as the prospects for reducing reliance on excessive cash bail.

Cynthia Golembeski provides an overview of the current state of the US cash bail system, writing that bail policies and practices are expensive, unjust to poor people and people of color, and may conflict with the US Constitution and Civil Rights Act and international human rights law. She discusses bail-related activism including community bail funds, as well as the prospects for reducing reliance on excessive cash bail.

Approximately 650,000 people are in US jails. Prior to COVID-19, nearly 200,000 people flowed into and out of jails weekly and 12 million people cycled in and out of 3,000 jails annually. Approximately 65 percent of those in jail are not convicted of a crime, legally presumed innocent, and unable to post bail.

In 2020, Neil Barsky, of The Marshall Project, penned The New York Times editorial citing COVID-19 as “an unfolding catastrophe” for the incarcerated and suggesting, “you can very possibly save a life by bailing someone out of jail.” The US and the Philippines are the only economically advanced countries that commercialize bail. Cash bail standards, for which much evidence of racial bias exists, are not based on availability to pay or standardized public safety or health concerns, but subject to jurisdictional discretion. The pandemic and its devastating effects on those living and working within correctional institutions has potentially increased attention towards state neglect alongside structural racism’s role in reinforcing deep social, economic, and political inequities.

Bail practices are unfair, undemocratic, and damaging at every stage

Well documented are the undemocratic practices associated with the criminal legal system, which permeate front end practices from arrest, bail determination, and pretrial detention to reentry and collateral consequences as part of the post-release period. Bail practices are unfair and unjust to poor people and people of color, who are disproportionately arrested, detained, and charged fees and fines. People remaining in jail prior to trial are more likely to receive harsher and longer sentences.

Much evidence outlines the harmful effects of jails and pretrial detention. Suicide rates in jails, which are over three times that of prison or general population rates, show the strain on jails as de facto health clinics. Experts and advocates suggest pretrial detention should be replaced by community-based alternative programs, especially for low-level, nonviolent crimes. Moreover, pretrial detention costs US taxpayers an excess of $14 billion annually, and $140 billion when factoring in impacts on families, communities, and social services.

Indeed, bail, which is cited in the 8th Amendment of the US Constitution, has a long history. Commercial bail bond companies emerged in the 1800s. Bail bond agents provide loans to vulnerable poor people desperate to release their child or loved one from jail. A small group of large insurance companies underwrite the bail industry with little regard for consumer protection or transparency. Bail bond agents take in over $2 billion from bond premiums and fees. Sixteen to $27 million were collected in New York City from non-refundable fees in 2017 alone. Commercial bondspeople and bounty hunters are incentivized to monitor clients, procure authority and power via private contracts without accountability checks posed by the Civil Rights Act or the Constitution. Fugitive recovery agents, or bounty hunters, can employ disruptive and even deadly tactics.

The civil rights implications of pretrial justice practices

In examining the civil rights implications of the current cash bail system, the US Commission on Civil Rights cites evidence of the arbitrary imposition of cash bail and related inequities. For example, Bureau of Justice Statistics data show that among the 75 largest US counties, 96 percent of felony defendants held pretrial had a bail amount set that they could not afford. To further illustrate, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) found that in Nebraska, identical offenses were associated with bail set at $10,000 in rural counties and only $5,000 in urban counties. A criminal legal system founded on a presumption of innocence, where “liberty is the norm, and detention prior to trial or without trial is the carefully limited exception,” conflicts with what has developed into the current US pretrial justice system where the median bail for a felony arrest is $10,000.

Constitutional concerns regarding excessive cash bail inform various legal challenges, largely involving assessments of the Fourth Amendment in relation to pretrial liberty; Eighth Amendment’s protection against excessive bail and fines, or cruel and unusual punishment; and Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection and due process clauses. In 2021, the California Supreme Court cited evidence of detention’s harmful effects on housing, employment, and a fair and adequate defense, and held that detaining people solely due to inability to pay bail is unconstitutional. A subsequent federal class-action lawsuit settlement agreement involving the ACLU resulted in Michigan’s largest district court reforming its bail practices and limiting imposition of unaffordable bail. Additionally, the International Bill of Human Rights interprets the US bail system as violating international human rights law.

Families acutely experience racialized harms of bail and pretrial detention. Recent research from the Pew Research Center finds that more than 80 percent of adults surveyed nationwide agree nonviolent crimes do not warrant pretrial detention: “the justice system should treat [people] more like innocent citizens than like criminals while they’re awaiting trial.” Cash bail system inequities and related reform efforts have led California, Illinois, New York, and New Jersey to reduce excessive cash bail reliance. Yet, there is resistance. California private bail bondsmen, who constitute 25 percent of the national private bail industry, sought to block a state referendum eliminating cash bail. Plus, the North Carolina Bail Agents Association requested that Senator Danny Britt sponsor a bill that was soon signed into law, which increases court collection of charitable bail organization information and commercial bail revenue opportunities.

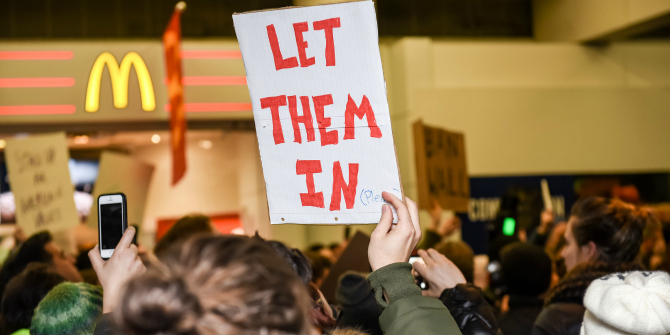

Photo by Syarafina Yusof on Unsplash

The state of bail reform

Careful analysis reveals recent increases in crime nationwide have occurred regardless of bail reform or similar decarceration policy enactment. Vera Center for Justice President Nick Turner’s 2022 The Washington Post article, “Bail reform did not spike crime,” states: “The best investments in public safety are investments in communities — such as violence intervention measures that prevent crime in the first place, pretrial services so that we incarcerate less, and reentry programs that rehabilitate.” Overall 2022 midterm elections did not appear to be swayed by fear of crime rhetoric in line with enacting the Willie Horton effect.

However, midterm election voters supported an Alabama proposition increasing the offenses for which one may be denied bail. Also approved was an Ohio constitutional amendment making it easier for judges to immediately deny bail, even though this was already possible with only a few steps. Two judges spoke out about Ohio’s amendment and misinterpretation of current state law, while underscoring judges’ common practice of denying bail or setting an unaffordable bail amount for this purpose already. Additional concerns include conflicts between the state and the US Constitution, which may increase legal challenges and related hurdles to justice and equity in the courts.

Despite support for reducing reliance on excessive cash bail, advocates fear some reforms, such as the use of risk assessments and preventive detention, may repeat race and class-based biases. Furthermore, alternatives to incarceration, including ankle monitoring devices, raise concerns regarding potential stigma, prohibitive set-up and daily fees, and limitations on freedom of movement that impair seeking out employment, maintaining positive social connections, and peace of mind. Ruha Benjamin conceptualizes tools perpetuating injustice including predictive policing programs, risk assessment tools, and electronic monitoring, as the The New Jim Code. Considering concerns that “mass incarceration” transforms into “mass monitorization,” Benjamin outlines the proliferation of abolitionist tools.

Related efforts include organized nonprofit bail funds, which were less widely known and commonplace until recently. The ACLU established a national bail fund in 1920 and the Civil Rights Congress (CRC) leveraged community donations to “make bail available to those charged with political crimes” during the 1960s and 1970s. From 2017 to this past year, the National Bail Fund Network grew to include over 90 community bail funds, while The Bail Project’s national revolving bail fund operated approximately 30 bail fund sites in 20 states. The Black-led National Bail Out collective also annually organizes Mama’s Day Bail Outs, which bail out Black caregivers so they can spend Mother’s Day with their families, and #FreeBlackMamas fellowships. Community bail funds and abortion funds aid more vulnerable people and raise awareness. Funds assist people in need and protect against risks to health, safety, economic security, social support, and presumption of innocence as an alternative to the commercial bail industry or pretrial detention.

Towards meaningful bail reform

The pandemic, recent reckonings, and midterm election results afford space to envision and actualize meaningful bail and pretrial reform and transformation. As bail amounts, related disparities, and jail populations have risen, inability to afford cash bail is a decisive factor for being incarcerated or accepting a plea bargain regardless of guilt or innocence. J ailing people who are legally presumed innocent simply due to inability to afford bail crystalizes how bail determination processes are consequential. Bail-associated harms make clear that poverty, structural racism, and inadequate care and support within jails and communities, combine with incarceration’s effects to further marginalize vulnerable people. Decarceration, drug policy and sentencing reform, and incarceration alternatives that strengthen positive community connections better address structural deficits further upstream and minimize additional harms.

- This article is based on the article “US Bail, Pretrial Justice, and Charitable Bail Organizations: Strengthening Social Equity and Advancing Politics and Public Ethics of Care.” In Public Integrity

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3Y1Xsnc