Americans increasingly dislike those who support the political party they oppose, but does this dislike also extend to those social groups they associate with the opposition, such as Christians for Democrats or LGBTQ people for Republicans? In new survey research of over 2,000 Americans, Jordan Brensinger and Ramina Sotoudeh explore what informs Americans’ attitudes towards 17 different social groups. They find that about 40 percent of respondents do use partisanship to organize their attitudes towards those social groups, about a third use racial identification to inform their attitudes, and the rest were neutral, potentially to appear more agreeable at times of social and political division.

Americans increasingly dislike those who support the political party they oppose, but does this dislike also extend to those social groups they associate with the opposition, such as Christians for Democrats or LGBTQ people for Republicans? In new survey research of over 2,000 Americans, Jordan Brensinger and Ramina Sotoudeh explore what informs Americans’ attitudes towards 17 different social groups. They find that about 40 percent of respondents do use partisanship to organize their attitudes towards those social groups, about a third use racial identification to inform their attitudes, and the rest were neutral, potentially to appear more agreeable at times of social and political division.

By many accounts, partisan antipathy in the US is both considerable and worsening. People increasingly dislike and distrust members of the opposing party, viewing them as hypocritical, selfish, and closed-minded. They even report that they have less willingness to marry or even socialize with them.

A growing related concern is that partisan antipathy of this sort is no longer limited to political identities. Democrats and Republicans may hold less favorable attitudes toward social groups that they associate with the political opposition, such as Christians for Democrats or LGBTQ people for Republicans. If true, political polarization may be broadly impacting how Americans view and treat each other according to their background, potentially threatening social cohesion.

How are Americans’ attitudes towards different social groups organized?

In new research we offer the first systematic examination of this phenomenon. We looked at how Americans organize their attitudes toward a host of social groups, including members of different sexual, religious, political, and racial identities. We aimed to understand what logics, if any, organize these attitudes while considering the role and relative importance of partisanship.

Identifying the logics behind people’s attitudes is a difficult task. It requires going beyond looking at attitudes individually to consider the relationships between attitudes and broader associated patterns. For example, people may report negative feelings toward Hispanics motivated by racial resentment or nativism. Only by viewing attitudes toward Hispanics alongside attitudes toward other groups can we begin to understand which of these logics is operating and for whom. For racial resentment, attitudes toward Hispanics would likely be similar to attitudes toward other marginalized racial groups. Nativism, by contrast, would lead to alignment between attitudes toward Hispanics and other groups conceived as non-American.

With this idea in mind, we used a method called Relational Class Analysis, which is uniquely suited to identifying logics in attitudinal data. We analyzed the attitudes of more than 2,000 Americans toward 17 different social groups, collected by the American National Election Study in 2016.

Many Americans’ attitudes are organized around a partisan logic, but the majority do not

As Figure 1 illustrates, we found some evidence of partisan identity bleeding into attitudes toward other, non-partisan, social groups. About 40 percent of the respondents in our data used a partisan logic to organize attitudes toward social groups. On the conservative side of this logic, people held positive attitudes toward conservatives, Christians, Christian fundamentalists, white people, and the rich and negative attitudes toward liberals, feminists, illegal immigrants, Muslims, and LGBTQ individuals. People on the progressive side of the logic held the opposite set of views. As expected, these individuals tended to identify more strongly with one of the two main political parties, pay more attention to news media, and express more interest in politics than respondents who did not evince the partisan attitude logic.

Figure 1 – Correlation between Party Identification and Attitudes toward Social Groups

Partisan divisions, however, tell only part of the story. We found two other main frameworks through which Americans see social groups.

More than a third of our respondents held attitudes organized according to a racial logic. These individuals distinguished racial groups — Asian Americans, Blacks, Hispanics and Whites — from other social groups. About half felt positively toward all the racial groups, while the rest felt negatively toward them. Racial minorities, and especially Black Americans, were more likely to adhere to this racial logic. Individuals reporting more first-hand experience of racial discrimination were also more likely to fall into this logic, and particularly on the side who viewed racial groups in a negative light.

Photo by George Pagan III on Unsplash

The rest of our respondents exhibited a neutral logic, reporting neutral feelings toward all groups in the data. These “neutrals” tended to be less interested in politics, pay less attention to news media, and otherwise look something like the average American in terms of their socio-demographics.

Strongly partisan Black Americans are more likely to have racially-based attitudes

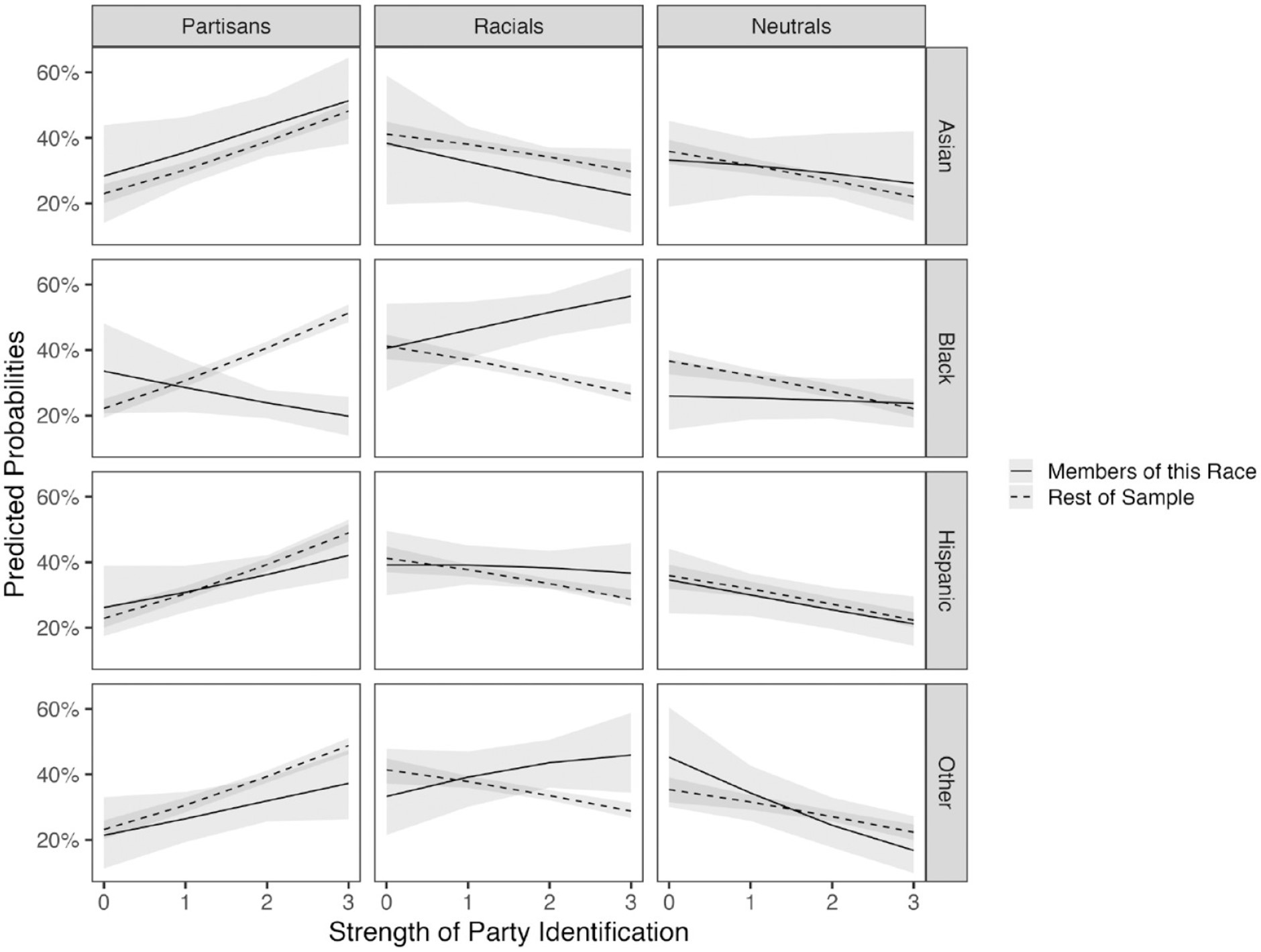

Broadly, our findings suggest that stronger partisanship corresponds to dividing social groups into hostile partisan camps. However, this is not universally true for all Americans and racial groups. This is shown in Figure 2, which visualizes the probability of belonging to each logic as a function of how strongly one identifies with a political party for each racial group. Black Americans with stronger party commitments were more likely to hold attitudes organized around a racial rather than partisan logic.

Figure 2 – Association between Strength of Party Identification and Attitude Logic, by Respondent Race

How might we explain this? Past research suggests that Black voters, despite holding a wide variety of religious and social values, consistently support the Democratic Party because they prioritize racial group considerations over values like religious and sexual conservatism. When it comes to social groups, a similar phenomenon might be at work. A high importance placed on racial considerations may lead Black Americans to express attitudes organized around race and ethnicity while having less structured feelings toward other groups.

Neutrality may be a way to appear more agreeable during divisive times

We were also interested in understanding “neutrals” and potential factors driving their attitudes. Prior research presented us with two competing expectations for their behavior: either they were “satisficers,” survey respondents who avoid expending cognitive effort by choosing neutral answers for all questions, or they felt unentitled to hold or express political attitudes.

We tested these competing hypotheses, first by comparing responses from individuals who took the survey online with those who did so face-to-face, and second by comparing how often neutrals responded “don’t know” to political versus non-political questions. If neutrals are really satisficers, we would expect to see them disproportionately represented among those who took the survey online, since individuals generally feel less pressure to take online surveys seriously. If instead neutrals are reluctant to express political opinions, we would expect them to say “don’t know” more often to political questions than non-political ones, and at greater rates than individuals in other logics. However, we did not find evidence to support either hypothesis.

We therefore propose a new possibility: as research has shown for political independents, these respondents may be expressing neutral attitudes to appear more agreeable at a time of perceived social and political division.

We believe that our results have important implications for how we understand political polarization. Americans’ attitudes toward social groups are not as influenced by partisan divisiveness as we might have expected given contemporary levels of party identification and antipathy. This may be somewhat encouraging for those who worry about the fracturing of American society along political lines. Even so, we believe that it will be important to continue to track the extent to which partisan antipathy is influencing social group attitudes going forward as an important barometer of social cohesion.

- This article is based on the article, ‘Party, Race, and Neutrality: Investigating the Interdependence of Attitudes toward Social Groups’, in American Sociological Review.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3iImqby