It has been clear for some time that billionaires wield informal political influence “behind the scenes,” but the rise of Donald Trump to the presidency has raised questions about the direct involvement of the ultra-wealthy in politics around the world. In new research, Daniel Krcmaric, Stephen C. Nelson, and Andrew Roberts study the global billionaire class’s involvement in politics. They find that 11 percent have held or sought political office, and that most tend to lean right ideologically. At 3.7 percent, the rate that US billionaires pursue office is significantly below the global average.

It has been clear for some time that billionaires wield informal political influence “behind the scenes,” but the rise of Donald Trump to the presidency has raised questions about the direct involvement of the ultra-wealthy in politics around the world. In new research, Daniel Krcmaric, Stephen C. Nelson, and Andrew Roberts study the global billionaire class’s involvement in politics. They find that 11 percent have held or sought political office, and that most tend to lean right ideologically. At 3.7 percent, the rate that US billionaires pursue office is significantly below the global average.

Donald Trump’s 2016 election victory marked the first time a billionaire ascended to the American presidency. After his win, Trump said that he wanted more “people who have made a fortune” in his administration. He made good on that claim by welcoming other ultra-rich individuals into his cabinet such as Betsy DeVos, herself a billionaire. Billionaire politicians have emerged on the side of the aisle, as well. Democrat J.B. Pritzker, heir to the Hyatt Hotels fortune, ousted near-billionaire Republican incumbent Bruce Rauner to become governor of Illinois in 2018. Two other billionaires – Michael Bloomberg and Tom Steyer – unsuccessfully sought the 2020 Democratic Party presidential nomination. Pritzker’s name is frequently floated as a future Democratic presidential candidate.

Billionaire politicians are not just an American phenomenon. From Silvio Berlusconi (Italy) to Sebastian Piñera (Chile) and Thaksin Shinawatra (Thailand), billionaires are now fixtures in politics around the world.

Our new research provides systematic evidence about the direct involvement of the ultra-wealthy in politics around the world. We find that billionaire politicians are common phenomenon: 11 percent of all billionaires have held or sought political office. Billionaire politicians are especially common in autocracies, lean to the right ideologically, and raise challenging dilemmas for politics today.

How common are billionaire politicians?

We used the Forbes Billionaires List to generate a global sample of ultra-rich individuals who might seek or hold political office. Given our interest in studying individuals who obtained wealth prior to entering politics, we took care to identify and remove the small subset of billionaires who held political positions before they acquired great wealth (e.g., Sheryl Sandberg and Pyotr Aven). We focused on formal political positions within a state’s established institutional structures. Examples of formal positions include national, state, or local executives, members of national or regional legislative bodies, cabinet-level positions or other appointed executive positions, and ambassadorships. Our dataset includes the political offices that billionaires have held as well as the positions that billionaires sought but failed to attain (such as when a billionaire ran for office but was not elected).

We find that the ultra-rich are frequent entrants into the political arena: 11.7 percent of the world’s billionaires have sought or held a formal political position (242 of 2,072 billionaires). Most not only sought but did in fact hold office. We identified only eight billionaires who sought office without ever attaining a political post at some point in their careers.

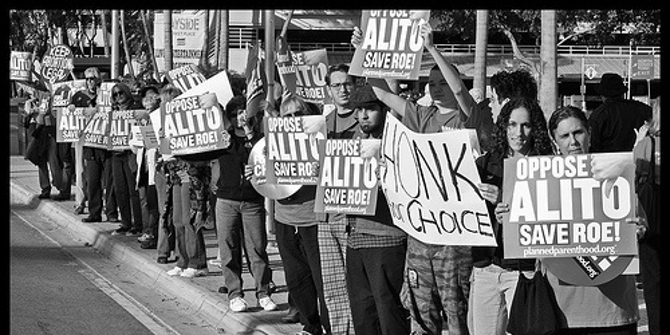

“Photo by Brendan Hoffman” (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) by Public Citizen

Where are the billionaire politicians?

One might expect that the number of billionaire politicians in a country is simply a function of the total number of billionaires in that country. But we find huge variation across countries in the rate of billionaire office-holding. At one extreme, billionaire political participation is well above the global average in China, Russia, Hong Kong, and Singapore. At the other end of the spectrum, we found no evidence that any of the 33 Japanese billionaires or 32 Australian billionaires ever pursued political office. The United States stands out as the country with the most billionaires, but the rate at which American billionaires pursue political office (3.7 percent) falls well below the global average.

More generally, cross-national variation in the rate of billionaire political entry correlates with regime type, as shown in Figure 1. Of the top twenty producers of billionaires, the highest rates of billionaire political involvement are in autocracies such as China and Russia. The rate of billionaire political participation falls as countries become more democratic (as defined by V-Dem’s polyarchy score).

Figure 1 – Billionaire Political Entry and Regime Type

Why are billionaire politicians more common in autocratic regimes? In autocracies, billionaire political participation seems to be motivated more by a desire to protect and expand wealth than to shape public policy. In weak institutional settings—such as those lacking fair elections and independent media—the superrich may be more likely to enter politics directly because doing so offers the best way to defend their financial interests. In China, for example, billionaires serving in the country’s rubber-stamp legislative bodies may garner approval from communist party leaders and acquire valuable political contacts that can help expand their financial interests. In countries like Russia, the ultra-rich may seek office—typically as an ally of the autocrat—to demonstrate fealty to the ruler and minimize the risk of wealth confiscation.

In democracies, “stealth politics” typically offer more efficient ways for billionaires to achieve their policy goals. Extreme wealth provides ample opportunities to exert influence informally by funding candidates or parties with compatible policy preferences, shaping media narratives, and developing personal relationships with professional politicians.

Are billionaire politicians different?

It’s not clear whether billionaire politicians’ policy preferences differ from those of other, less affluent politicians. This is a hard topic to study because billionaire politicians hold a variety of different positions (heads of state, mayors, cabinet members, etc.). But most billionaire politicians do make one comparable decision: the decision to join—or, in some cases, found—a political party.

We therefore compared the ideological positions of the political parties that billionaires joined to the ideological position of the median political party in their countries. Using data from the V-Party dataset, we found most billionaire politicians belong to parties that tilt to the right ideologically. In fact, nearly three quarters of billionaire parties were to the right of the median political party in their country.

The representation-transparency tradeoff for billionaire politicians

Should people be worried about the rise of the billionaire politicians? Rather than give an easy answer to this hard question, we identify a thorny dilemma.

On the one hand, there are good reasons to view billionaire politicians as a cause for concern. Billionaires often bring a distinctive set of life experiences and political preferences into office that do not represent the interests and beliefs of most citizens. Moreover, they can spend enormous sums of money on campaigns that effectively increase the barriers to entry for less affluent candidates.

On the other hand—and this is where the dilemma arises—billionaires do not need to pursue formal office to impose their political preferences. Instead, billionaires can exert influence behind-the-scenes in the form of stealth politics. Secretive forms of influence are, by their very nature, unaccountable. Using the massive financial resources at their disposal, billionaires can quietly steer the political agenda in their preferred directions without facing the judgment of the voting public—perhaps even without the public ever knowing about their political activities. By contrast, when billionaires directly enter the political arena as candidates in democracies, it involves at least some basic level of accountability and transparency.

Consider the revelations that two billionaires – real estate tycoon Harlan Crow and investor Paul Singer – paid for US Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito to take lavish trips around the world. When billionaires subsidize the lifestyles of Supreme Court justices, it creates conflicts of interest and the appearance, if not the reality, that an ultra-rich individual may be able to “buy” the loyalty of a judge with a lifetime appointment to America’s highest court. Yet the ties between the billionaires and the justices remained secret until a bombshell ProPublica investigative report was published in 2023. Would it have been better for the health of American democracy if Crow and Singer ran for office—and faced the accompanying public scrutiny—instead of wielding influence behind closed doors? There is no easy answer when it comes to managing this tradeoff between representation and transparency for the billionaire class.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Billionaire Politicians: A Global Perspective’, in Perspectives on Politics.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3tkDgTe

1 Comments