There has been a growing trend for institutional investors to purchase single-family homes and convert them to permanent rental properties. At the same time, homeownership rates for Black households have declined on par with the Great Recession. In new research, Stephen Billings and Adam Soliman find that investor purchases led to a decline in property values for nearby homes, almost exclusively in Black neighborhoods, as well as an increase in crime and reduced political participation and property maintenance.

There has been a growing trend for institutional investors to purchase single-family homes and convert them to permanent rental properties. At the same time, homeownership rates for Black households have declined on par with the Great Recession. In new research, Stephen Billings and Adam Soliman find that investor purchases led to a decline in property values for nearby homes, almost exclusively in Black neighborhoods, as well as an increase in crime and reduced political participation and property maintenance.

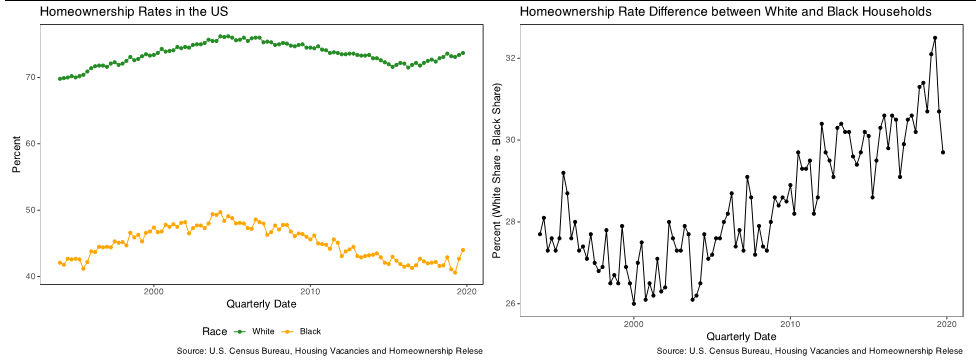

Two concerning trends for Black households in the United States have developed over the past decade. First, the century long progress in decreasing the wealth gap between Black and White Americans has stalled, and since the Great Recession, it has even grown for many households. Second, homeownership rates have declined during this time, but have fallen faster for Black families – see Figure 1. Our new research finds that large institutional investors play a significant role in driving these racial gaps in homeownership and wealth creation.

Figure 1 – US Homeownership rates 1990-2020

The rise of institutional investors in single-family homes

Given that institutional investors have often hidden their property holdings through subsidiaries and corporate holding companies, we began by documenting the scale of this activity. We find that 7 percent of all single-family homes sold between 2011 and 2021 in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina were purchased by institutional investors. Focusing on neighborhoods that were ever targeted by these firms, this becomes almost 12 percent of all homes sold.

“For Rent” (CC BY 2.0) by ishane

The investment strategy of these firms, which began in the wake of the Great Recession, is to purchase single-family homes and convert them to permanent rental properties. We find that they tend to target suburban starter homes built in the 1990s and 2000s with above average build quality, which allows them to consolidate the income flows from renting the property quickly. This primarily affects Black households, as they moved to these neighborhoods when older housing stock and centrally located areas became the focus of gentrification. As seen in Figure 2, more than 75 percent of these transactions occur in majority Black neighborhoods. These transactions also lowered overall homeownership rates for existing homes by two percentage points in the county overall and four percentage points in Black neighborhoods specifically. This is a decrease that approaches the overall loss in homeownership due to the Great Recession.

Figure 2 – Transaction share by race of neighborhood

The effects of increasing corporate investment in neighborhoods

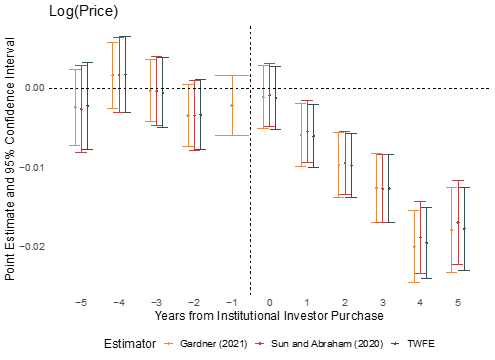

In terms of spillovers to neighboring property values, Figure 3 shows that homes close to an institutional investor purchase saw a dynamic price decline that reached 2 percent, relative to homes located just slightly further away. These price declines are limited to Black neighborhoods and stronger for institutional investor purchases made later in our study period.

Figure 3 – Prices of transacted homes near institutional investor purchase

We then examine the social spillovers of this large-scale loss of homeownership and show impacts on reported crime, building permits, code violations, and political participation. More specifically, we see increases in property crime of two percent, increases in violent crime of three percent, and increases in drug crime of nine percent. We also see a thirty-six percent decrease in building permits, which would be required for any new construction, reconstruction, or repair, and an eight percent increase in nuisance code violations, such as for junk cars on lawns, an accumulation of trash, or tall grass. Lastly, we test for the role of political participation and find a one percent decrease in the number of registered voters.

Our results have important implications for policy, especially since this activity is not limited to Charlotte, North Carolina. The focus of institutional investors on Black neighborhoods highlights the importance of local governance. For example, limiting negative spillovers onto minority neighborhoods may require stronger neighborhood organizations to thwart institutional investors from converting these homes to rentals and eroding home equity. There is also room for improved tenants’ rights, accountability of corporate landlords, and transparency of investor’s property holdings. More broadly, our results suggest that homeownership is still important, as it generates positive social spillovers to neighborhoods, and historical efforts to broaden homeownership through cheaper financing and tax advantages for home purchases may be beneficial.

Technical Note

To generate casual estimates of the price effects on neighboring properties, we incorporate granular definitions of treated and control areas around the focal investor-purchased property. Given the spatial pattern of institutional investing and the scale of spillovers highlighted in our results, we limit our analysis to transacted sales that are within 500 feet of an institutional investor purchase and compare them to neighbors that are from 500 to 1000 feet away. This research design limits concerns about any unobserved neighborhood attributes confounding our results as well as controls for any larger market demand effects from institutional investors. Subsequently, we apply this same spatial difference-in-differences (DID) model to a number of other outcomes typically associated with spillovers of homeownership.

- This article is based on the LSE CEP Discussion Paper No. 1967, ‘The erosion of homeownership and minority wealth’

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3GO7eSD