In recent decades, as many of the largest and most economically successful cities in the US have increased their connections with other global cities, many smaller US cities have become increasingly disconnected from these global centres. In new research, Max Buchholz and Harald Bathelt examine the recent history of US “hinterland” cities, finding that since 1993, their economic – especially manufacturing – and social connections to larger global cities have declined. They also find that these cities did not replace these lost connections with links to other locations, and that these declining links are likely to have compounded the trend of rising socioeconomic disadvantage in these cities.

In recent decades, as many of the largest and most economically successful cities in the US have increased their connections with other global cities, many smaller US cities have become increasingly disconnected from these global centres. In new research, Max Buchholz and Harald Bathelt examine the recent history of US “hinterland” cities, finding that since 1993, their economic – especially manufacturing – and social connections to larger global cities have declined. They also find that these cities did not replace these lost connections with links to other locations, and that these declining links are likely to have compounded the trend of rising socioeconomic disadvantage in these cities.

We live in an increasingly interconnected world. Firms have massively expanded their economic relations to others across the globe. And yet, despite this rising connectivity, many smaller US cities have become increasingly disconnected from the major US global centers to which they once had substantial economic linkages.

Ironically, this disconnectedness is occurring when the connections between firms seem to be an increasingly important determinant of their success and the success of their local areas and regions. In the so-called “knowledge economy” firms make investments across the globe to gain knowledge about different technologies and production processes, and to access new markets. These firm-level linkages increasingly connect remote locations and generate important positive impacts on employment and wages at home and abroad.

In our research, we use data on firms’ ownership networks, which allow us to identify the other cities to which a firm in a specific location has ownership connections for the years 1993 and 2017. Our research shows that most US “hinterland” cities (those with a population under 250,000 people in 1990 and at least one ownership connection to a US global center in 1993) have become disconnected from US “global centers” (eight major cities with the most foreign ownership connections in 2017) to which they once had corporate ties. This is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 – Changes in Ownership Connections Between US Global Centers and Hinterlands, 1993-2017

Data source: Authors’ calculations with data from LexisNexis Corporate Affiliations, 1993-2017.

Connectivity between cities has increased, but not for hinterlands

Between 1993 and 2017, the global centers we examined, on average, had declines in connectivity to their hinterlands (apart from Houston). This is shown at the bottom of the figure. Most of this decline occurred in manufacturing. Notably, this is not just about a handful of hinterlands that used to be well-connected with major US cities, most hinterlands experienced declines in ties to their respective US global centers. This is in line with popular and academic narratives which have speculated that major US cities have increasingly reduced connections to smaller hinterland cities, to which they once had significant economic and social ties.

While this may confirm our intuition about changes in the US urban system over the past 50 years, general trends in corporate connectivity between US cities suggest the opposite should have happened. This is indicated in the top and middle sections of Figure 1. While hinterlands in the US became increasingly disconnected from global centers, overall connectivity between cities increased exponentially and US global centers became dramatically more connected with each other, and with international locations. The disconnectedness of hinterland urban regions thus occurred at a time when other urban areas expanded their connections with each other. We believe that this could be an important factor in the rise of spatial inequality that we see in the US since 1980.

These findings are striking and strongly support the widespread perception of an increasing “left-behindness” of many smaller US cities. But these results also pose further questions.

Photo by Devin Avery on Unsplash

For one, is it possible that those hinterlands which became disconnected from their US global centers found better opportunities to connect to larger markets and technological knowledge through connections to other cities, nationally and internationally? In this case, these cities may have excelled along many socioeconomic indicators, and may not have substantially relied on the few connections they had to global centers in the US.

Have hinterland cities been able to make connections with other cities?

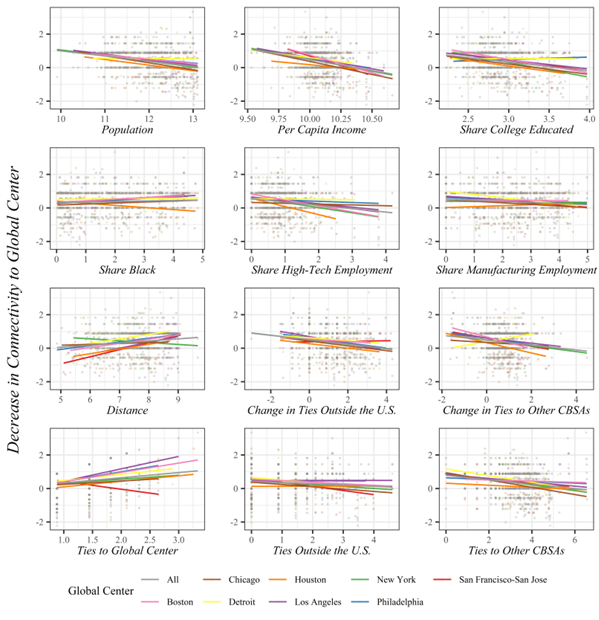

We investigated this possibility by examining how hinterlands’ changes in connectivity to their respective global centers are related to a range of socio-economic and network variables. This again revealed some striking patterns, as shown with a series of scatterplots for each US global center in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Hinterland Cities’ Patterns of Decreasing Connectivity to US Global Centers over Different Socio-Economic and Network Variables, 1993-2017

Notes: All variables are transformed using the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation. Graphs are derived from the authors’ calculations using census data from IPUMS’ NHGIS for 1990, industry data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages for 1990, and LexisNexis Corporate Affiliations for 1993-2017.

First, hinterlands which became disconnected from their respective global centers tended to have more ownership connections to their global center in 1993, but fewer to other cities in the US urban system and around the world (bottom row). This suggests that hinterlands which lost connections to their global centers were more reliant on those connections. Second, more disconnected hinterlands usually had smaller increases or even declines in the number of connections to other cities in the US and around the world (second to last row). This means disconnected hinterlands did not substitute lost connections to US global centers with more connectivity to other locations. Finally, the figure reveals that hinterlands which became disconnected from US global centers tended to have smaller populations, lower per capita incomes, lower shares of college-educated residents and high-tech workers, and higher shares of Black residents in 1990, as well as are located farther away from their global centers.

The story of declining economic opportunity in US hinterland cities

We can combine these empirical results into a stylized story that may highlight the experience of many of the small hinterland cities in the US.

Imagine a small urban area located far away from any major city. As recently as 1993, there were a handful of firms in this small city, especially in manufacturing, which were owned by larger firms in a major urban center. These manufacturing firms created a substantial number of jobs in that community, provided access to new technologies and wider markets, and generated spillovers into other local sectors (as manufacturing workers spent money on local goods and services and manufacturing firms purchased local inputs). Today however, these ownership connections have mostly disappeared. Some of the manufacturing plants have shut down completely, while others have been bought by other firms and now employ fewer workers. Compounding all this is the fact that already in the 1990s, this small city was socioeconomically disadvantaged in many respects.

Our data suggests that this might be a common story for many smaller US urban areas. Empirical research on the possible negative and inequality-producing impacts of globalization thus far has mostly focused on import competition, but recent conversations around “left-behind places” and regional inequality have emphasized that the nature of the relationships between cities has fundamentally changed. Our results highlight an urgent need for place-sensitive policies that redress the lack of economic opportunity in small US hinterland cities.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Relational hinterlands in the USA have become disconnected from major global centres’, in the Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3RMjGbO