The general trend of upward economic growth in the US has not encompassed every town, city, or municipality. In new research, Dylan Connor looks at the unfolding social and economic conditions of over 20,000 places in the US and how these conditions affect intergenerational mobility among children growing up in lower income households. Among these children, he finds that those who live in an economically “left behind” place experience a four-percentile reduction in adult income level compared to those in more advantaged areas. Addressing the issues posed by left behind places, he writes, demands nuanced policy solutions which account for the circumstances of each community and the broader regional context.

The general trend of upward economic growth in the US has not encompassed every town, city, or municipality. In new research, Dylan Connor looks at the unfolding social and economic conditions of over 20,000 places in the US and how these conditions affect intergenerational mobility among children growing up in lower income households. Among these children, he finds that those who live in an economically “left behind” place experience a four-percentile reduction in adult income level compared to those in more advantaged areas. Addressing the issues posed by left behind places, he writes, demands nuanced policy solutions which account for the circumstances of each community and the broader regional context.

At first glance, one would struggle to identify two more different places than Gary, Indiana, and Guadalupe, Arizona. Nestled on the south shore of Lake Michigan, Gary was once a juggernaut in North American steel production. The city boasted a population of almost 200,000 before the deindustrialization and “White Flight” in the late 1960s. In contrast, Guadalupe, a municipality within the Phoenix metropolitan area, occupies a mere square mile and is home to fewer than ten thousand residents. Embracing the motto “where three cultures flourish”, the town serves as a melting pot, blending its Yaqui Indian, Mexican, and agricultural roots. Despite the divergent scales and histories of these places, they share surprising and important similarities.

In new research we illuminate the connection between places like Gary and Guadalupe by their shared experiences of being left behind amidst decades of broader economic growth. The condition of “left behindness” manifests in declining relative income and education levels, coupled with high rates of poverty and unemployment. Our research underscores that the repercussions of this condition are enduring, leaving a lasting impact on entire generations of children raised in struggling locales. Significantly, both Gary and Guadalupe find themselves in the bottom 15 percent of places for upward income mobility, highlighting the persistent challenges these communities will face over the generations to come.

Studying left behind places

Our study undertakes is first comprehensive analysis of the issue of left behind places and its impact on intergenerational mobility. By intergenerational income mobility, we mean the degree to which children born to lower income parents can climb the income ladder as adults. To achieve this, we constructed a new multidecadal database of the social and economic conditions of over 20,000 places in the United States. This database also incorporates information on the intergenerational income mobility of children raised in these locales.

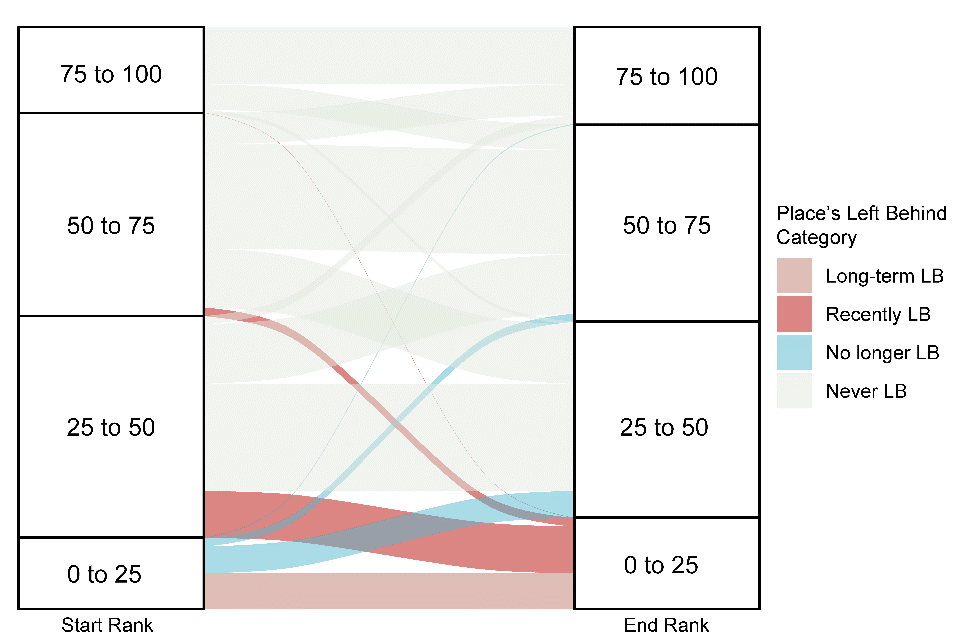

Defining the criteria for what constitutes a left-behind place is crucial for both scientific analysis and effective policy action. We devise a “Left Behind Index” that describes every place in the United States based on changes in local education levels, poverty and unemployment rates, and average incomes over the study period. Our concern is with two kinds of places: the ‘long-term left behind’ struggling over extended historical periods and the ‘recently left behind’ where conditions have deteriorated more recently (Figure 1).

Figure 1- Trajectories of places across their economic rank

By using these data, we study the geography of left behind places in the United States. Additionally, utilizing estimates from Opportunity Insights, based on records from over 20 million children, we examine the income attainment of the individuals who grew up in these places, even among those who relocated as adults. Our primary focus is on children who grow up in analogous low-income households, yet in communities that exhibit differing trajectories over the time which we studied.

Living in a left behind place can hamper incomes long-term.

We find that exposure to a left behind place during childhood significantly hampers long-term income attainment. Among otherwise similar children in terms parental income, race, ethnicity, and region, growing up in a left-behind place is associated with a 4-percentile reduction in adult income levels. To contextualize this gap, four percentiles is approximately the difference between Mississippi, the poorest performing state in terms of income mobility, and a more mid-ranking and growing state like Arizona.

Crucially, we find that exposure to places undergoing economic improvement enhances children’s prospects. The stark contrast in outcomes between those growing up in left-behind places and those in areas experiencing economic growth underscores the profound impact of local economic dynamics on social mobility. Furthermore, these effects endure even among individuals who leave their childhood locations, indicating that migration is an insufficient remedy for the problems created by left behind places.

“20200718 05 Gary, Indiana” (CC BY 2.0) by davidwilson1949

Concentrated disadvantage can amplify the effects of left behind places.

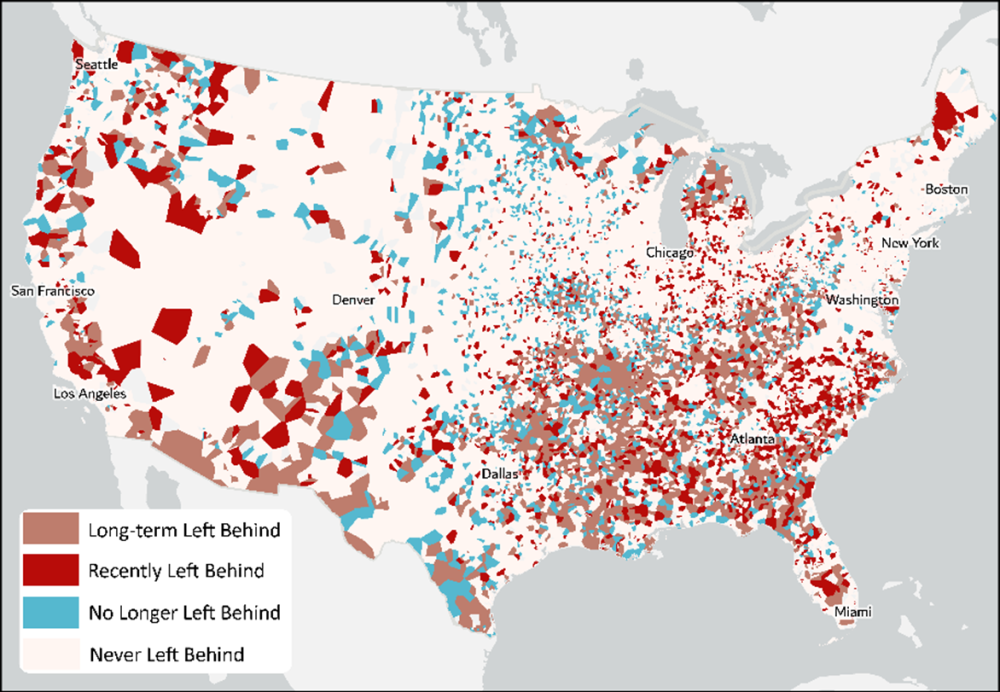

These effects are amplified when neighboring places also confront adversity, highlighting that these effects tend to be strongest when disadvantage is highly concentrated within regions. As Figure 2 shows, concentrated disadvantage is most prominent in the South, where substantial urban and rural areas fall below the national average in terms of poverty and income levels.

Figure 2 – Place-level trajectories across the United States

Moreover, we explore how these dynamics unfold across different social groups. Notably, Black, Hispanic, and Native American households disproportionately reside in left behind places. This means that young people of color are more likely to be exposed to the challenges that arise in these contexts. However, within social and racial groups, the largest inequality in upward mobility is observed between whites who grew up in left behind places and whites who grew up in more economically dynamic places. This observation potentially contributes to an understanding of the political polarization of white voters over recent decades.

Complex circumstances need nuanced policy solutions

Our research underscores the necessity for nuance in addressing the challenges presented by left-behind places. While improvements in local economic conditions and migration to more prosperous areas may mitigate some issues, they are unlikely to serve as complete remedies. Addressing the complex interplay of factors demands thoughtful strategies that account for the unique social circumstances of each community and its broader regional context.

In parallel research, we establish that these challenges extend beyond economic ones. Localized disruption and stagnation have the potential to undermine community and family support mechanisms, further entrenching intergenerational disadvantage long into the future. This is particularly relevant given that children growing up in places with cohesive households and communities tend to show greater resilience in the face of adversity. A self-reinforcing dynamic thus emerges from left-behindness, where economic hardships place stress on families and communities, subsequently curtailing economic prospects for the emerging generations in these places. The interplay of economic and social factors underscores that families and communities are fundamental in the problems posed by left behind places.

Identifying and examining left-behind places is a crucial foundation for formulating effective policies aimed at breaking the cycle of inequality. We have made our data and methods accessible to facilitate further investigation into the issue of left-behind places. Such resources are pivotal, especially as it becomes increasingly evident that adopting a comprehensive and localized approach is essential to uplift communities and pave the way for a more equitable and harmonious future.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Who gets left behind by left behind places?’ in the Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society.

- The research described here is based on collaborative work with Tom Kemeny (University of Toronto), Peter Kedron (UC Santa Barbara), and Aleksander Berg (University of Colorado).

- The data underlying this analysis are also made available online.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3vVQqXu