In 2019, Panama released a study showing it had registered a staggering 4,060 domestic NGOs since 2000. This surge in NGOs is closely related to the intensity of the ongoing Central American migration crisis. For more than a decade, Gabriela Valencia has been championing the service and invaluable contributions of these local NGOs in addressing critical issues. However, her recent observations have revealed challenges to their agency and development approaches, stemming from what they perceive as uneven strategies aimed at governing migration in Central America.

In 2019, Panama released a study showing it had registered a staggering 4,060 domestic NGOs since 2000. This surge in NGOs is closely related to the intensity of the ongoing Central American migration crisis. For more than a decade, Gabriela Valencia has been championing the service and invaluable contributions of these local NGOs in addressing critical issues. However, her recent observations have revealed challenges to their agency and development approaches, stemming from what they perceive as uneven strategies aimed at governing migration in Central America.

Furthermore, recent research that I completed, examined how tackling migration crises through the US’s ongoing Collaborative Migration Management Strategy, shapes the capacity and agency of local NGOs to deliver services in migrant-receiving countries. It highlighted the concern that transnational governance not only shapes development but also contributes to domestic competition and inequality for NGOs.

The American Strategy to Control Migration (and Development)

Latin America has long been considered by the US as their nearest ‘backyard.’ Fourteen days after Joe Biden was sworn in as the US President in 2021, the White House passed an Executive Order that called for a ‘strategy to collaboratively manage migration’ in the North and Central America regions. This collaborative strategy represents the external half of Biden’s administrative policy for addressing the issue of migration. The transnational strategy was intentionally designed to rectify the use of the controversial Title 42 policy. It was also unilaterally constructed to allow the US to regain control of its Southern border by tackling the ‘roots’ of displacement and addressing the flow of forced migration that has been rapidly incrementing and concentrating in the region.

Sprinkled throughout the strategy are terms like ‘stabilize’, ‘expand’, ‘strengthen’, ‘support’, and ‘enhance’, implying that development is an integral part of it. On the surface, the approach seeks to comprehensively refresh ties and sustain the co-responsibility of migration management by having the US work alongside and support its long-time Central American allies. In a polarised fashion, other weighty terms used in the strategy are ‘govern’, ‘manage’, and ‘orderly process’. This dual approach allows the US to put forward a blueprint based on governing through aid and development.

For Central America, ‘migration control remains closely linked to relations with the U.S’ and because the assistance to migrant populations is primarily carried out by local NGOs, they have become pivotal to the complex migration governance strategy. Small host countries such as Belize, Costa Rica, and Panama are being asked to make every effort to not only assist and aid the extremely vulnerable migrant populations but to also curb their mobility towards the North by providing economic development and social integration programmes. While the US pushes to externalise migration issues and regain its regional hegemony, local NGOs are immersed in a political hot zone.

The role of Panamanian NGOs in the response to the migration crises

The existence of numerous NGOs in Panama is not without justification. Primarily, in Latin America, NGOs are often seen as a substitute for the shortcomings of state development. They enhance the role and representation of civil society in areas where fundamental needs are perceived to be inadequately addressed. In Central America, this perception is further shaped by nearly a decade of evolving migration crises converging within its borders.

From January to December 2023, the Panamanian government registered irregular entry through the Darien Gap of over 500,000 migrants from three main regions: South America, Antilles, and Asia. The primary attendants of these migrants are relief-oriented United Nations agencies, NGOs, and underserved communities that can assist them with their most immediate needs such as access to water, food, shelter, and healthcare.

Because of migration policies and their irregular status, the long-term settlement of most migrants will remain uncertain. Once their pressing needs are met, they will attempt to access other services (i.e. economic development, legal assistance, and social integration programmes) that will allow them to build some temporary stability in Panama. To provide such services, many local NGOs have partnered directly with UN agencies to access funding and strengthen their service capacity. By aligning with the strategy, the NGOs can access larger grants that are trickled down from the US through their main contractors such as USAID, UN agencies, and INGOs.

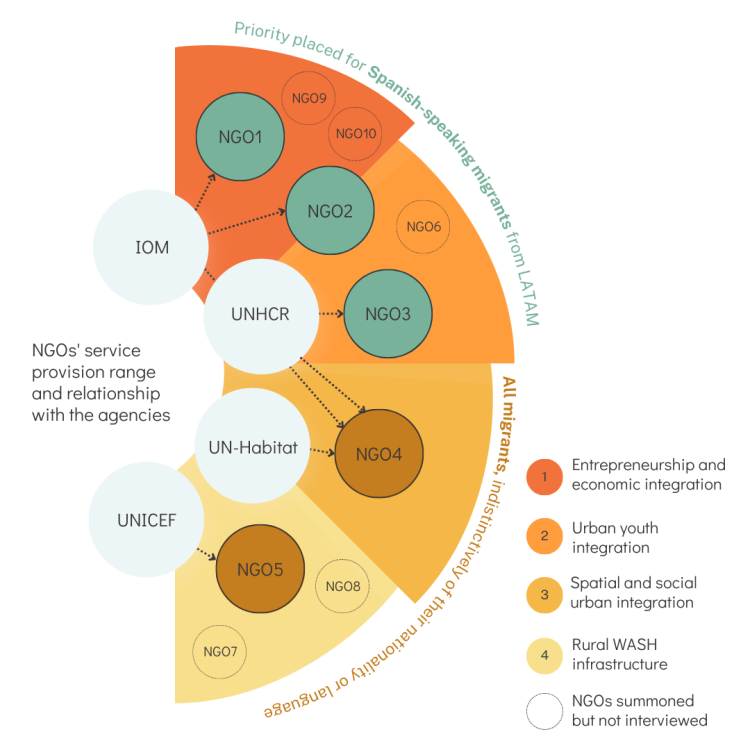

Figure 1 – NGO’s service provision range and relationship with agencies

The relationship of the UN Agencies, the NGOs of the study, and the services and types of migrants they assist.

Yet, even when the local NGOs can manage to acquire more funds to advance the services and learn to navigate the bureaucratic hurdles of the UN system, they will still find themselves adopting formidable obstacles in the form of economic instability and development constraints far beyond their participation in the strategy.

Cracks in the strategy: Unrealistic expectations, competition, and inequality

So far, the Mexican and Central American states’ capacity to respond to the current migration crisis has been limited. This results in an overreliance from the governments and international agencies on civil society organisations to aid and put forward responsive migration programmes through intensely transactional relationships. Local NGOs have quickly found themselves balancing economic dependency and advancing their development goals. They are continuously consumed and preoccupied by the inequalities within the systems they navigate.

Experiences of civil society organisations in Panama point to a highly competitive atmosphere to attain the grants and to impact a specific number of migrants without necessarily being able to recognise them as significant assets for the country and endure the impact. It seems like the scarce resources available continue to be directed indefinitely into providing temporary relief in what can be perceived as a never-ending cycle of humanitarian assistance. Therefore, as funding levels surge, these NGOs find themselves navigating a nuanced landscape filled with challenges that pose conflicts for their overarching mission and the effective delivery of services. The complex role that these NGOs have within the strategy is widely relevant to understanding the mechanisms, procedures, and establishments that sustain inequality within the aid system.

While a definitive solution to the Central American migration crisis remains elusive, the collaborative strategy persists on its course toward implementation. Anticipating further participation from NGOs and agencies, I will continue my work with the aim of responding to the need for a more comprehensive analysis of the strategy’s implications and the role of local organisations in the Central American migration service system.

- This article originally appeared at the Atlantic Fellows for Social and Economic Equity blog.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, the Atlantic Fellows for Social and Economic Equity programme, the International Inequalities Institute nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://wp.me/p3I2YF-dDw