While in theory a president’s power should end when they end their term in office, they can often wield considerable influence after they leave the White House. In new research, Gregory H. Winger and Alex Oliver explore the power of what they term the ‘Rhetorical Post-Presidency’. Using surveys to test the influence of former presidents’ statements on certain policy issues, they find that former presidents can influence public opinion, but that this often depends on the president and the issue. They also find that Donald Trump’s toxicity with Democratic voters fell between 2020 – when he was president – and 2022 – after he left the White House.

While in theory a president’s power should end when they end their term in office, they can often wield considerable influence after they leave the White House. In new research, Gregory H. Winger and Alex Oliver explore the power of what they term the ‘Rhetorical Post-Presidency’. Using surveys to test the influence of former presidents’ statements on certain policy issues, they find that former presidents can influence public opinion, but that this often depends on the president and the issue. They also find that Donald Trump’s toxicity with Democratic voters fell between 2020 – when he was president – and 2022 – after he left the White House.

Donald Trump’s campaign to retake the Presidency has invariably been shaped by his unique personality and political brand. Yet Trump’s efforts have also highlighted the American post-Presidency as a peculiar political institution. Since the earliest days of the Republic, ex-presidents have refused to retreat into anonymous retirement, but have instead leveraged their privileged status to continue influencing public affairs. Through prominent episodes like Ronald Reagan’s endorsement of gun control legislation and Jimmy Carter’s criticism of the Iraq War, we have become accustomed to the platform that is available to ex-presidents and their capacity to shape the national discourse.

We argue that the growth in post-presidential influence is a byproduct of the growth of informal presidential powers during the 20th century – and especially the emergence of the Rhetorical Presidency. While a president’s official powers end when they exit the White House, their rhetorical standing endures and continues to underpin post-presidential activities. To explore this Rhetorical Post-Presidency, we conducted survey experiments to test the influence of former presidents as elite cue-givers. We find that while former presidents can meaningfully shape public opinion in ways that can even rival the sitting President, these effects are highly personalized and vary significantly across individual, issue, and time.

Life after the presidency

The invention of the American post-Presidency was a historical accident that was itself a revolutionary act. In an era dominated by monarchies – where a king’s tenure was for life – the idea that a head-of-state’s term would expire before he did was a profound departure from the political norm. However, beginning with George Washington’s decision to forgo running for a third term, the handover of presidential power has been a cornerstone of American democracy.

But the transfer of formal presidential powers does not mean that ex-presidents are powerless. Outside their constitutional authorities, presidents enjoy a bevy of informal powers that they continue to wield long after leaving the White House. In The Rhetorical Presidency, Jeffrey Tulis detailed how presidents draw power not only from their constitutional role, but also their unique ability to cultivate a direct relationship with the general public. Communication technologies like radio, television , and social media have allowed the presidents to communicate directly with the American people and use their status as figureheads to mold the national agenda. Wielding this public platform has been the most common form of post-presidential activity – and a frequent bane to successors. For example, Herbert Hoover fiercely opposed FDR’s New Deal, and Theodore Roosevelt’s roasting of Woodrow Wilson’s policies during World War I became so blistering that The Nation openly wondered why Roosevelt was not jailed for sedition.

How effective are interventions from former presidents?

But do these post-presidential interventions matter? From Obama’s evangelizing to Donald Trump’s tirades, are former presidents still relevant opinion makers – or merely political afterthoughts yelling at clouds on Fox News? To test the hypothesis of a Rhetorical Post-Presidency, we conducted survey experiments to evaluate what impact statements attributed to ex-presidents have on public preferences towards policy issues. Participants recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (mTurk) platform were randomly assigned to read a story about either pirate activities in the Gulf of Guinea or a territorial dispute with China in the South China Sea. Afterward, participants all read the identical proposals for a US foreign policy intervention, but the statements were randomly assigned to one of five possible speakers: either a Department of Defense (DoD) spokesperson, (then) current President Donald Trump, or former Presidents Barack Obama, George W. Bush, or Bill Clinton. Participants were then asked a series of questions about their preferred policy for addressing the situation.

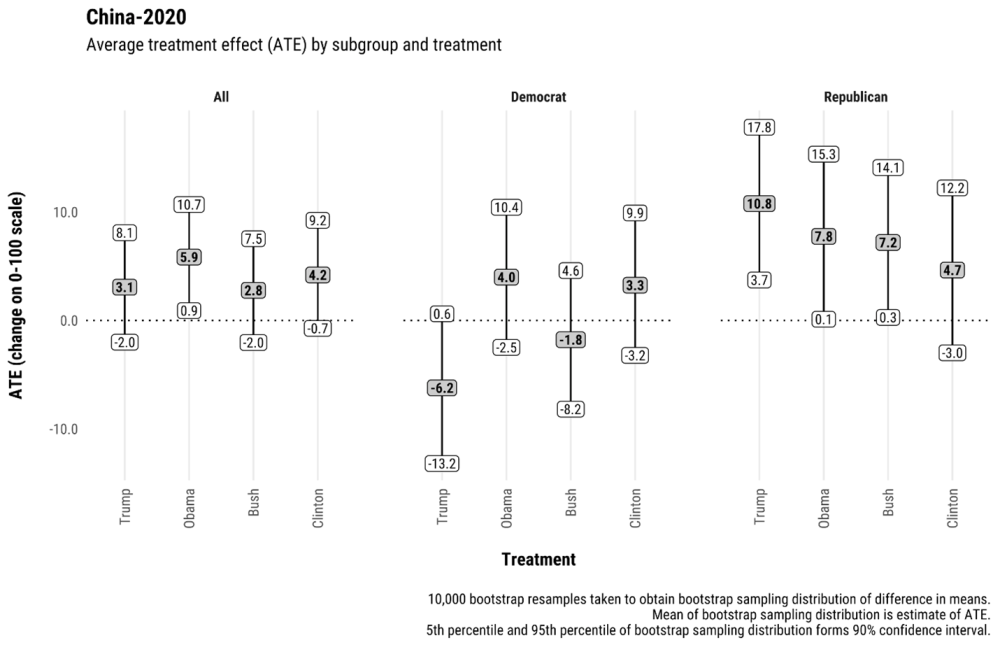

Our initial experiment was fielded in February-March 2020 and recruited a sample of 1,902 respondents. Figure 1 below shows are results.

Figure 1 – Impact of statements from current and former presidents

We replicated the earlier experiment in April-June 2022, with a sample of 2,018. The only differences between the initial and replication experiments were the addition of current President Joe Biden as a potential cue-giver and the description of Donald Trump was changed from “current” to “former” president. Results for the 2022 China scenario are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Impact of statements from current and former presidents, with Joe Biden added

Post-presidential appeal

In both experiments, we found evidence that at least some of the Presidency’s rhetorical power extends into the post-Presidency. However, this influence appears idiosyncratic, with differences in impacts across experiments, vignettes, and cue-givers. For example, George Bush was an effective cue-giver in the context of the 2020 China vignette for Republican participants, but this result did not replicate in the 2022 study. The opposite pattern occurred for Bill Clinton amongst Democrat participants. Indeed, while the specific contours of post-presidential appeal remain elusive, partisanship appears to be a critical factor. While there were repeated instances of ex-presidents motivating those from their party (e.g. Clinton with Democrats), there was only a single instance (Obama in the 2020 China vignette) where a former president had statistically significant cross-partisan appeal.

“P042513PS-1332” by the Obama White House Archived is United States government work

Last, Donald Trump’s presence in both our 2020 and 2022 experiments presented a unique opportunity to examine whether the transition from sitting president to former president altered his ability to wield rhetorical power. Admittedly, there are several intervening factors that frustrate a perfect case comparison across time. Trump’s failed 2020 reelection campaign, the January 6, 2021, Capitol insurrection, and presumptive 2024 campaign all make Trump a distinct case even among ex-presidents. Moreover, although our samples are comparable on key demographics of party, gender, and age distributions, any differences in results may stem from shifts in the sample itself rather than treatment effects.

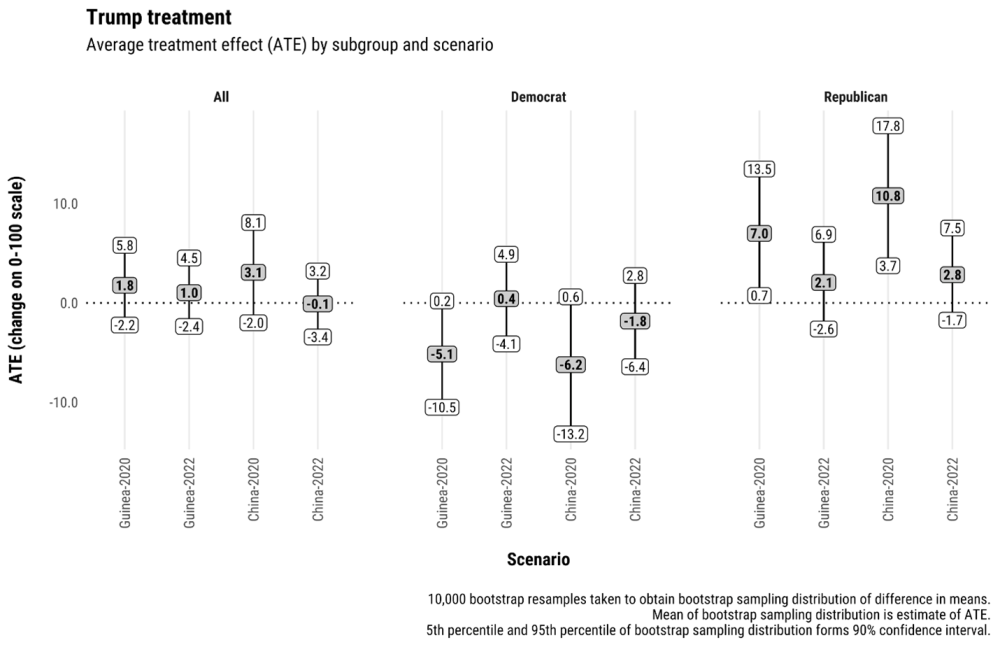

Despite these caveats, this is a relatively rare opportunity to empirically assess the post-presidential transition and it did yield some interesting insights. Notably, while not statistically significant, as Figure 3 shows, Trump appeared to be a less toxic cue-giver among Democrats in 2022 even after his very Trumpian exit from office. Conversely, while Trump was an effective cue-giver for Republicans in 2020, this influence faded after leaving office. This finding has implications for the 2024 election.

Figure 3 – Impact of statements from Donald Trump

It is worth recalling that Grover Cleveland was not just the only ex-President to retake the White House, but he was also the only ex-President to successfully win his party’s nomination. If after leaving office, a president’s influence wanes within his own party (as our findings suggest), the Republican primary contest may have been the historically more significant challenge for Trump. At the very least, Democrats appeared less averse to Trump as a former president in 2022 than as a sitting president in 2020.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The Rhetorical Post-presidency: Former Presidents as Elite Cue Givers’ in Political Science Quarterly.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://wp.me/p3I2YF-dFm