Among Americans belief in climate change and its human causes is not geographically uniform across the US. In new research Trung Vu looks at the link between US historic ‘frontier’ counties and climate change beliefs. He relies on the idea that Americans who now live in what were frontier counties in the 17th and 18th centuries are more likely to display cultural traits of rugged individualism, including self-reliance, independence, and strong anti-statism. These traits in turn, he writes, mean those in these areas are more likely to support populist movements opposed to climate action.

Among Americans belief in climate change and its human causes is not geographically uniform across the US. In new research Trung Vu looks at the link between US historic ‘frontier’ counties and climate change beliefs. He relies on the idea that Americans who now live in what were frontier counties in the 17th and 18th centuries are more likely to display cultural traits of rugged individualism, including self-reliance, independence, and strong anti-statism. These traits in turn, he writes, mean those in these areas are more likely to support populist movements opposed to climate action.

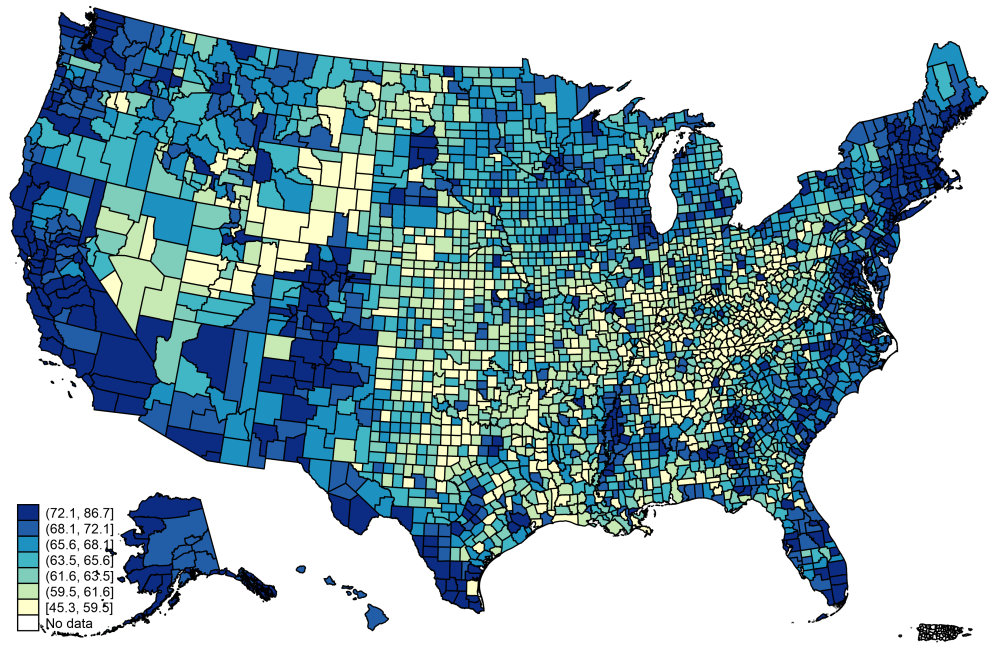

There is a widespread consensus among scientists and policymakers that climate change is one of the most serious barriers to fostering sustainable development. In recognition of this, strengthening collective responses to changing climate conditions is part of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) under SDG 13. Cooperation in the climate commons (where all countries have a role in either contributing to or mitigating climate change) depends critically on public awareness and policy support. Estimates indicate that 63 percent of Americans believe that global warming is happening and only 47 percent believe in human-induced climate change. Moreover, as shown in Figures 1 and 2, climate change scepticism has large and persistent variations across counties in the United States, making it difficult to implementing national, state, and local mitigation and adaption policies.

Figure 1 – Cross-county variation in climate change beliefs in the United States

Notes: This figure depicts the variation in the estimated percentage of adults who believe that global warming is happening across counties in the United States. Darker areas correspond to counties with a greater prevalence of climate change beliefs. Data were taken from Howe et al. (2015).

Figure 2 – Cross-county variation in belief in the human causes of climate change in the United States

Notes: This figure depicts the variation in the estimated percentage of adults who believe that global warming is caused mostly by human activities, assuming that it is happening. Darker areas correspond to counties with a greater prevalence of climate change beliefs. Data were taken from Howe et al. (2015).

In light of the importance of fostering public support for climate change mitigation and adaption policies, my new research uncovers one of the deepest roots of observed differences in climate change responses across counties in the United States. In particular, I focus on the central role of a persistent culture of ‘rugged individualism’ – shaped overwhelmingly over a process of rapid population growth and westward expansion in early American history – in driving the evolution of risk perceptions, societal non-cohesiveness and populism, thereby undermining collective responses to climate change. My findings indicate that US counties with a greater prevalence of cultural traits of rugged individualism, including self-reliance, independence and strong anti-statism, tend to have lower estimated percentages of pro-climate perceptions and environmental underperformance, and are less prepared to address the consequences of climate change.

Photo by Taylor Brandon on Unsplash

The formation of cultural traits of rugged individualism in early American history

To understand the cultural origins of collective climate action in the United States, I draw on the important work of historian Frederick Turner who in 1893 documented that long-term exposure to the American westward-moving frontier line between 1790 and 1890 was conducive to the formation of cultural traits of rugged individualism. Specifically, various waves of European settlements in early American history contributed to the westward movement of the American frontier line, which separated densely populated settlements from those with low population density. Counties on the frontier line were characterized by isolation from urban settlements in the east and limited interaction with the federal government. Low population density also implied that frontier settlers had little social infrastructure to rely on for survival. Therefore, most independent, and adventurous people were attracted to frontier counties during the process of the westward expansion of the American frontier line. On this basis, recent work established that US counties with longer periods of frontier exposure from 1790 to 1890 are now endowed with pervasive cultural traits of independence, self-reliance and a strong antipathy to government intervention.

How does rugged individualism affect collective climate action?

My results are based on cultural theory highlighting the importance of social values and worldviews in forming risk perceptions, thereby driving public awareness of climate change and policy support. Specifically, individualistic cultures, by awarding social status to individuals’ independence and accomplishments, incentivize public support for market-based strategies that maximize autonomy and personal gains, leading to greater antipathy to government regulation. By contrast, group-oriented people place emphasis on social order and compliance with social norms and have a higher propensity to take collective interests on board. Furthermore, non-individualistic people tend to express greater trust in authority, such as experts, scientists, and the government, when it comes to assessing risks of climate change. This line of argument suggests that cultural traits of rugged individualism undermine pro-climate perceptions and support for climate change mitigation policies.

Frontier counties are also characterized by strong antipathy to government redistribution and hence populist attitudes tend to be more common. This is because populist leaders have obtained greater public support for populist movements through a transition to less government intervention. Given that populist-oriented individuals typically consider climate-related issues to be elite-driven concepts, rugged individualism undermines collective responses to climate change by inducing persistent distrust in political institutions and strong anti-statism. This underlines the argument that frontier counties with a persistent culture of rugged individualism are characterized by pervasive populist attitudes, thus creating barriers to sustaining cooperation on climate change.

Empirical evidence on the impact of rugged individualism on collective climate action

Using the length of time (in decades) of frontier exposure as a county-level measure of the prevalence of cultural traits of rugged individualism, I find evidence suggesting that rugged individualism has a negative influence on climate change beliefs and policy support in the United States. My results also indicate that counties with greater exposure to the historic American frontier line have poorer environmental performance and are less prepared for climate change mitigation. Evidence from individual-level analyses reveal that people living in what were frontier counties are less likely to believe in climate change and support pro-climate action. These findings highlight the long-term legacy of deep-rooted cultural traits for collective climate action. This implies that the feasibility and efficacy of climate change mitigation policies are contingent on their compatibility with the prevailing cultural environment. It is therefore suggested that strengthening collective climate action critically requires attention to the persistent influence of cultural traits of rugged individualism on climate change perceptions and policy support.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Individualism and Collective Responses to Climate Change’, in Land Economics.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://wp.me/p3I2YF-dLr