In the aftermath of WWI global women activists saw a moment to empower women in the peace negotiations and seek a new order, one that was inclusive of women’s rights and where women held a voice in the establishment of a lasting peace. In this article, Mona Siegel draws on her new book Peace on Our Terms: The Global Battle for Women’s Rights After the First World War detailing the stories of women activists, their efforts to champion a different type of peace and how they left their mark on the emerging fundamental principles for democracy and social justice.

“When I hear that women are unfit to be diplomats,” wrote British pacifist Helena Swanwick in 1935, reflecting back on the peace negotiations at the end of the First World War, “I wonder by what standards of duplicity and frivolity they could possibly prove themselves inferior to the men who represented the victors at Versailles.” Her words, though cynical, are understandable. By the time Swanwick penned this scathing critique of the Paris Peace Conference and its attendant treaties, the Nazi Party had seized dictatorial control in Germany; Mussolini’s troops were preparing to march on Ethiopia; and the Japanese, ensconced in Manchuria, were looking towards Shanghai. To a lifelong feminist and pacifist like Helena Swanwick, one did not need a wild imagination to think that women might well have designed a more effective and enduring peace than had the Allied statesmen in the aftermath of the First World War.

Global women’s activism

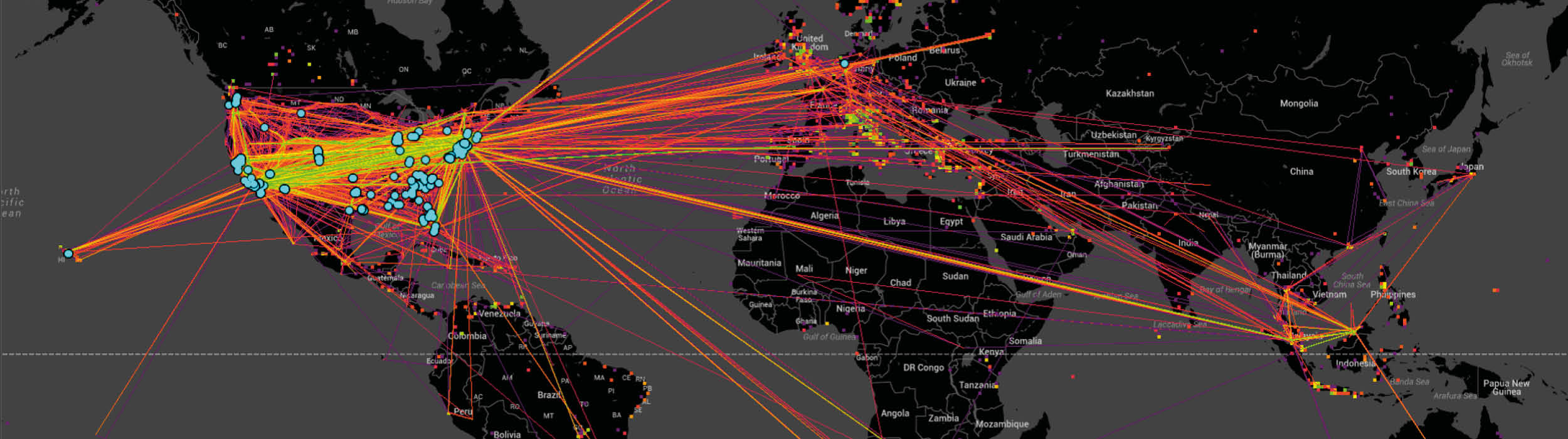

What few recognised at the time Swanwick was writing, and what historians and international policymakers have long since forgotten today, is that women did try to champion a very different type of peace settlement at the end of WWI. Indeed, 1919 saw a virtual explosion of global women’s activism spurred directly by the catastrophic conflict of 1914-1918 as well as by Allied leaders’ promise to fashion the peace settlement around the collective goals of mutual security, democratic governance, social justice, and national self-determination. The Paris Peace Conference may indeed have been a man’s peace, but not for lack of effort on the part of women activists who literally crossed oceans and continents to demand a voice in the historic negotiations.

On January 18, 1919, the very day the Paris Peace Conference opened, French suffragist Margarite de Witt Schlumberger announced women’s arrival on the global stage. On that day, she drafted a letter to American President Woodrow Wilson imploring him to ensure that the peace conference “give vocal expression to more than half of humanity represented by women who in so many countries have been condemned to an unjust and cruel silence by the denial of the vote.” Political rights were foremost on Schlumberger’s mind, as they were for many other Western suffragists in 1919, but women’s vision did not end at the ballot box. National sovereignty, military disarmament, citizenship rights, racial justice, international governance, sexual servitude, educational opportunities, marital equality, maternity rights, and equal pay: these issues and others drew women across the ocean and into the streets to demand social, economic and political justice in a new world order.

Paris was the epicentre of world government in 1919, and many women converged there. Schlumberger and French suffragists quickly convened an Inter-Allied Women’s Conference to press an agenda of women’s economic and political rights in the drawing rooms of the peace delegates. At the same time, a handful of prominent African American women—including pan-Africanist Ida Gibbs Hunt and civil rights activist Mary Church Terrell—journeyed to the French capital, boldly demanding racial and gender equality in a new world order. In the meantime, the revolutionary Chinese nationalist Soumay Tcheng took a different path to Paris. Appointed as an official attaché to her country’s peace delegation, Tcheng would play a decisive role in determining whether China would agree to sign the Versailles Treaty at all.

The Paris Peace Conference may indeed have been a man’s peace, but not for lack of effort on the part of women activists who literally crossed oceans and continents to demand a voice in the historic negotiations

People worldwide avidly followed the discussions in Paris, recognising that the array of territorial, political, and economic issues on the table would have repercussions around the globe. Women’s political activism in 1919 took full account of the diverse geographic and thematic scope of these debates. Feminist pacifists, under the leadership of Jane Addams, gathered in Zurich, denounced the Versailles Treaty as a vindictive peace (the first international body to do so), and organised women to promote international cooperation and disarmament.

In Washington D.C., trade unionists convened the first-ever International Congress of Working Women to confront the infant International Labour Organization over questions of protective legislation for working women. In Beijing and Shanghai, female students helped lead the mass May Fourth protests against the peacemakers’ sacrifice of Chinese national interests to the Japanese, while in Cairo, elite women, led by nationalist, philanthropist, and budding feminist Huda Shaarawi, took to the streets to demand sovereignty from the British. Both Chinese and Egyptian women gave voice to growing movements dedicated to the intertwined goals of female and national liberation.

The explosion of female activism around the world in 1919 was truly historic. The peacemakers’ failure to address women’s concerns was a global tragedy, which neither historians nor policymakers have adequately reckoned with.

Inter-Allied Women’s Conference delegates standing in front of the Lyceum Club, February 27, 1919, National Archives and Record Administration, War Department, Record 533768.

A new world order

A century after the Allied Powers and Germany signed the Versailles Treaty in the gleaming Hall of Mirrors, diplomatic historians have grappled with the multiple and complex repercussions of the post-World War I peace treaties. These scholars—including Canadian historian and recent LSE featured speaker Margaret MacMillan—have explored the relationship between the false hopes raised by the Peace Conference and the triumph of fascism in Europe in the decades that followed from almost every imaginable angle. Others—led by Harvard historian Erez Manela—have pointed to African and Asian disillusionment over the false promise of national self-determination as a major factor that would drive many anticolonialists into the hands of the Communists in interwar decades and after. For all their aspirations toward liberal internationalism and global security, the peacemakers of 1919 were deeply committed to their own national interests, including a world order rooted in imperial domination. This much, historians have made clear.

Female demonstrators in Cairo, 1919

The exclusion of women’s rights

Less understood or appreciated is the degree to which the Versailles Treaty and the other international agreements stemming from the post-WWI peace negotiations represented a concerted defence by Western statesmen of a patriarchal political and social order. Contrary to the pleas of women activists, the peacemakers of 1919 declined to make any principled stance on behalf of global women’s enfranchisement, validating the assumption that democracy and a just world order could be built to women’s exclusion. The men who crafted the peace of 1919 were also careful to recognise women’s political legitimacy only in so far as it had a direct bearing on women and children’s specific interests. Ironically, on the core diplomatic issues of the day, statesmen saw women as too peace-loving to be trusted with peacemaking.

By failing to empower women in the negotiations or to endorse democratic governance in the settlement, the peacemakers declared the issue of women’s rights to be peripheral to the central goal of establishing a lasting peace. Women disagreed, and history—sadly—has borne out their concerns.

Header image: Delegates to the First International Congress of Working Women, Washington, D.C., October 28, 1919, Library of Congress.

This blog is part of the Gendered Peace project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 786494).

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.