In this blog Professor Christine Chinkin reflects on a century of women’s activism at the International Labour Organisation and looks at what lessons can be gained for the current Women, Peace and Security agenda. This blog is an adapted version of a chapter that appears in ILO 100: Law for social justice titled ‘Enhancing the impact of international norms with special reference to women’s labour rights and the Women, Peace and Security agenda’.

In her recent blog, Peacemaking and women’s rights…a century in the making, Mona Siegal referred to what she called “a virtual explosion of global women’s activism” in 1919, much of which was targeted at the terms of peace in the wake of World War I. Part 13 of the Versailles Treaty – the Constitution of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) – is often overlooked in discussions of the Treaty, although the Organisation survived the League and celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2019. Women activists also directed attention toward this body that was created to give innovative weight to the centrality of social justice and higher living standards for universal and permanent peace. This blog reflects on women’s ambitions with respect to the ILO and how these remain relevant in the Security Council’s agenda on Women, Peace and Security (WPS).

Suffrage, peace and labour conditions for working women

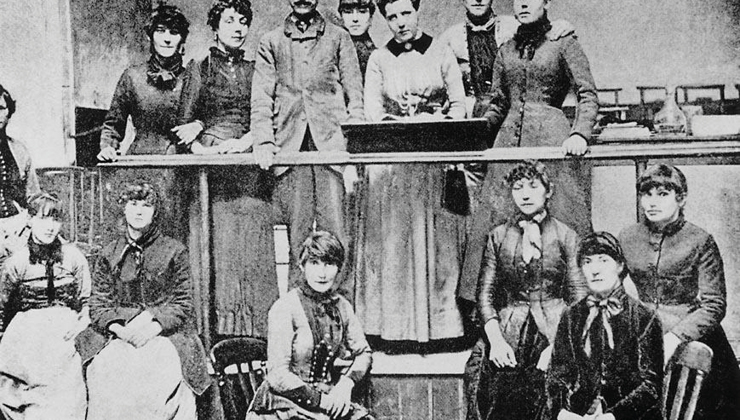

From at least the mid to late 19th century women mobilised transnationally around suffrage, peace and labour conditions for working women. The last was expressed through women becoming delegates to trade unions, forming their own unions and strike action, such as the match girls strike in 1888 against the working conditions in the Bryant and May factory in East London. In 1919 women were present at two significant gatherings that made calls to the Paris peacemakers relating to these three issues. In Berne in February women attended what was essentially the peace conference of the international labour movement that demanded an International Labour Charter to be included in the Treaty. But women’s participation in Berne did not denote access in Paris. George Barnes, a British delegate to the International Labour Commission at the peace talks, expressed his “angry astonishment” that Sophy Sanger, who had been appointed to the Berne Conference as an expert by the British Government and later became the first woman professional staff member in the ILO, had not been invited to meet the British representatives to the International Labour Commission when she passed through Paris on her way to Berne.

Match Workers Strike Committee, 1888. Copyright, TUC Library.

Match Workers Strike Committee, 1888. Copyright, TUC Library.

The Resolutions

Unlike the Labour Conference where some women participated in a predominantly male event, the other meeting was all women – the second Congress of what became the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), now the oldest women’s peace organisation. In Zurich in 1919 it adopted a set of Resolutions that selected delegates presented to the Peace Conference. The Resolutions urged the insertion of a Women’s Charter into the Peace Treaty to include wide-ranging principles relating to recognition of women’s social, political and economic status, including that:

- Educational opportunities be open to both sexes;

- Women have the same opportunities as men for training, for entering industry and professional life;

- Women receive the same pay as men for the same work;

- Adequate economic provision be made for the service of motherhood;

- Mothers have equal guardianship rights over their children;

- Married women have equal nationality rights.

Women’s wishes with respect to the proposed Labour Organisation were not just about substantive rights but also centred around participation, albeit in a narrower sense than with respect to political status. Women wanted to be part of the radical idea of representation in an international organisation. There may also have been the realisation that if some matter is omitted from the outset of a new institution it is hard subsequently to gain its inclusion, a lesson of many contemporary agreements. Women therefore sought guaranteed places in country delegations to the ILO. For instance, the Zurich Resolutions had urged that in the interests of women workers worldwide the International Labour Commission’s proposal that each country have two delegates – one representative of employers and one of employees – be amended to provide that one of these be a woman. At the International Congress of Working Women held later in 1919, simultaneously with the first Annual Conference of the male-dominated ILO, women labour leaders from around the world recommended to the ILO Conference that the number of country delegates be increased from four to six and that two of the six be women. Neither proposal was accepted.

Women sought other forms of participation in the fledgling Organisation. A British TUC General Council member, Margaret Bondfield, is credited with lobbying the British delegate, George Barnes, to propose that when any question concerning women was under discussion at the General Conference a woman adviser should be present and that the Director of the future Organisation should employ a ‘certain number of women on his staff.’ The first was brought into article 389 of the Covenant – “When questions specially affecting women are to be considered by the Conference, one at least of the advisers should be a woman” – and the second into article 395 – “The staff of the International Labour Office shall be appointed by the Director, … A certain number of these persons shall be women”. These lack precision in that article 389 provides for a woman “adviser” rather than a representative and stipulates that such adviser need only be present for consideration of questions that ‘affect’ women, a compromise that fails to realise that this is the case for all work-related matters. If read in that light it would guarantee women’s presence in all situations. Article 395 does not specify a specified number or percentage of staff members but requires only that a “certain” number be appointed. Nevertheless, they provide for some women’s participation including on specialist Commissions and in preparation of ILO Conventions and Recommendations. Along with the preambular assertion of the importance of improving working conditions for the “protection” of women and recognition of the principle of equal remuneration for work of equal value, articles 389 and 395 make the ILO exceptionally women-friendly for an international governmental organisation of its time and indeed much later.

Along with the preambular assertion of the importance of improving working conditions for the “protection” of women and recognition of the principle of equal remuneration for work of equal value, articles 389 and 395 make the ILO exceptionally women-friendly for an international governmental organisation of its time and indeed much later

Differences of opinion

Women activists continued to lobby the ILO after its creation, but they did not speak with a unified voice. There were significant differences of opinion around many subjects including which women should be designated as workers, especially pertinent in light of women’s unpaid work and participation in the informal economy. But the issue that has continued throughout international law’s encounters with women was disagreement as to the better approach for addressing women’s situation. On the one hand was the demand for equality and on the other ensuring the protection of women, in particular of their supposed vulnerabilities, reproductive capacities and ideals of womanhood. Or to put it another way, are the interests of women in the workforce better advanced through giving ‘special attention’ to women’s ‘special needs’, even if this denies women’s autonomy, limits their access to better paid jobs and reinforces stereotypes of women as vulnerable and as supporting family life in the home, not at work. Or is the alternative approach of gender neutrality and equality more favourable, allowing women ostensible choice and agency but with the norm remaining that of the male worker in a workplace designed around male working lives? This reflects and foreshadows the still ongoing debate as to whether women’s rights are better upheld through specialist women-centred institutions with the corresponding risks of essentialism and marginalisation, or through gender mainstreaming with the different risks of submergence and loss.

On the one hand was the demand for equality and on the other ensuring the protection of women, in particular of their supposed vulnerabilities, reproductive capacities and ideals of womanhood

Despite an assertion of equal remuneration in article 427 of the Treaty, in 1919 the approach was primarily protective as exemplified by the ILO Conventions on Maternity Protection and on Nightwork (the former has been revised and the latter revoked). But this characterisation is complex as the former Convention both protects women from certain forms of work during and after pregnancy but also provides for the payment of benefits. Over time the ILO has moved towards an equality approach while also taking some account of the need for targeted interventions to redress structural obstacles to achieving women’s workplace equality and to address forms of work that are dominated by women, for example the Domestic Workers Convention (2011).

Over time the ILO has moved towards an equality approach while also taking some account of the need for targeted interventions to redress structural obstacles to achieving women’s workplace equality and to address forms of work that are dominated by women

Many of women’s demands from 1919 have entered international law albeit in piecemeal fashion and slowly. A major step forward was the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, especially article 11, with respect to workplace equality. Others are included in the Security Council’s WPS agenda for bringing women’s experiences of conflict into peace processes and agreements. But women remain greatly under-represented and their participation has to be repeatedly urged. And social justice barely figures in the WPS resolutions that remain in many ways “protective”’ of women’s “special needs.” There is no systematic inclusion of secure livelihoods and the ILO fundamental principles of decent work and social protection floors that are core to post-conflict relief and recovery are not included within WPS. The disconnect between women’s peace and human rights activism and principles of labour remains largely intact 100 years after the Versailles Treaty.

This blog was written with the support of the Arts and Humanities Research Council grant called ‘A Feminist International Law on Peace and Security’ and a European Research Council (ERC) grant under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 786494).

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.