12 million girls are forced into marriage each year with devastating health and socio-economic outcomes for child marriage survivors. Ana Belén Perianes details the effects, exacerbated by the current COVID-19 pandemic, and why there is a continued need for this to be raised as a critical issue in order to fully achieve the Women, Peace and Security Agenda.

Girls are much more vulnerable to child, early and forced marriage in conflict-affected settings, post conflict and humanitarian crises.

Child, early and forced marriage is a major violation of human rights which remains widespread around the world across many cultures and religions, affecting both boys and girls. But child marriage impacts disproportionately on girls in developing countries (about 18% of those married before age 18 are boys whilst around 82% are girls) and this harmful practice is exacerbated in times of crises and conflicts. Because of that, it is essential to progress towards the eradication of child, early and forced marriage if we are to fully achieve of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda.

Although the incidence of child, early and forced marriage is decreasing globally, the total number of child brides remains very high. Despite most countries having already enacted laws against child marriage, the number of girls married in childhood stands at 12 million per year, which means that every two seconds a girls is married against her will. Today, there are around 650 million girls and women alive married before their 18th birthday.

Factors that increase the risk for child marriage are exacerbated by violence and humanitarian crises

Many factors increase the risks for girls to be vulnerable to child, early and forced marriage, including poverty and economic instability, structural gender inequality, the perception that marriage provides ‘protection’ to them, ‘family honour’, social norms or inadequate legislative frameworks.

The worsening of conditions resulting from violence or vulnerability in conflict-affected settings, post conflict situations or humanitarian crises leads families to often view child marriage as a way to protect themselves from poverty and daughters also from sexual violence. But sometimes, early and forced marriage can be a form of slavery, sexual exploitation and trafficking of human beings. Consequently, child, early and forced marriage rates increase in conflict-affected situations, post-conflict and humanitarian settings, including refugee camps and contexts of forced displacement. For instance, it in Lebanon, 41% of young displaced Syrian women are married before 18; in Yemen, child marriage rates have increased from 50% to 65% since the beginning of the conflict and, in countries highly affected by violence such as Nigeria, 44% of girls are married before the age of 18.

the number of girls married in childhood stands at 12 million per year, which means that every two seconds a girl is married against her will

Evidence does not support the belief that child brides are protected by their husbands. In this regard, girls who are married early and forced into marriage are more likely to suffer high levels of sexual, physical and emotional violence from their intimate partners; to contract HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases and they remain poorer than unmarried girls. Child brides are also much more likely to leave school prematurely and to become pregnant when their bodies are not mature enough to give birth, facing a much higher risk of maternal and newborn mortality. In addition, evidence-based research conducted by the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and the World Bank notes that child brides are more likely to be isolated from family and friends, to be excluded from participating in their communities and to have lower socioeconomic outcomes, trapping them in a cycle of poverty, gender inequality and disempowerment at all levels.

Countries with the highest rates of child marriage are considered fragile states

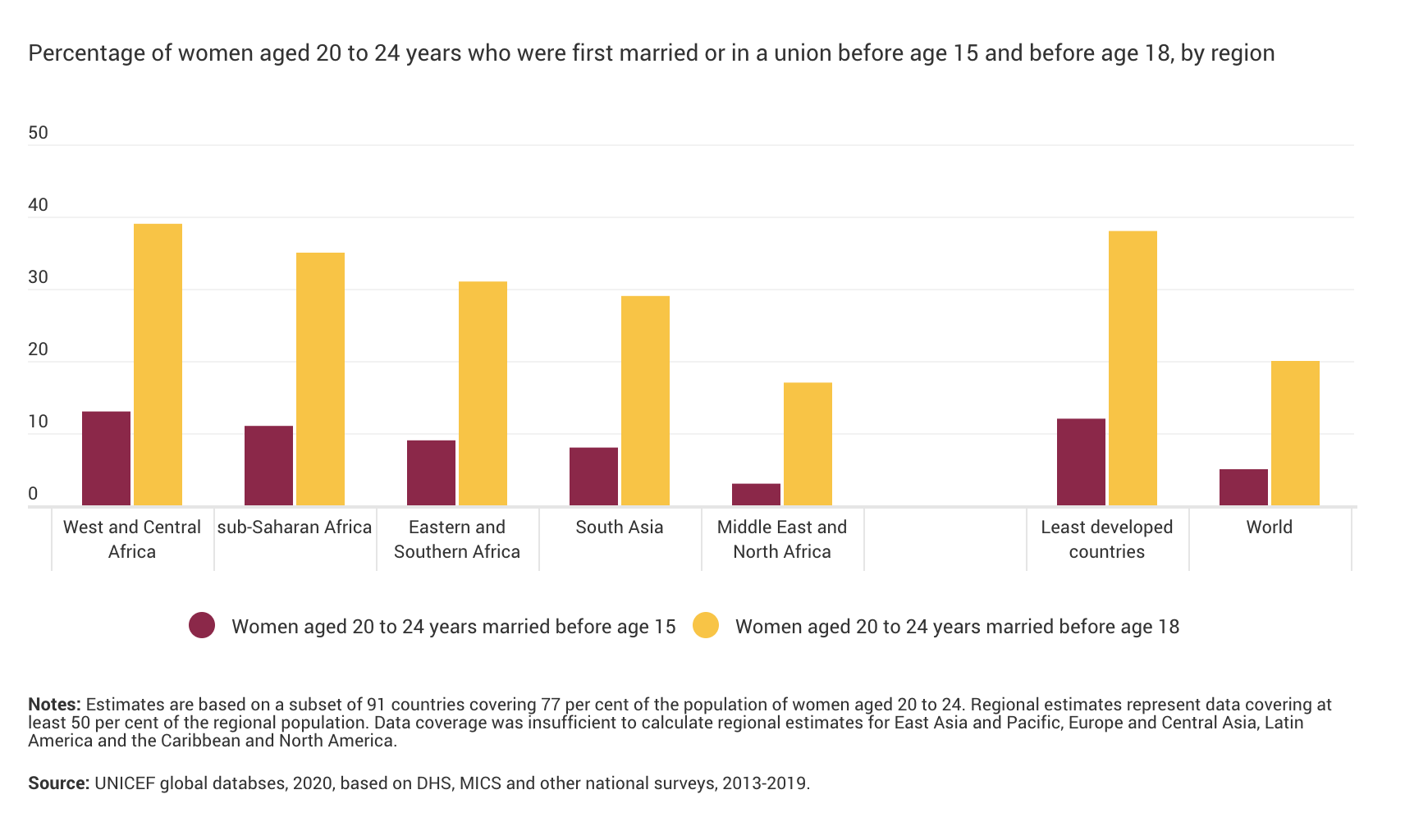

The highest levels of child marriage are found mainly in sub-Saharan Africa (with nearly 4 in 10 young women married before age 18), followed by South Asia (where 3 in 10 girls are married before age 18). Nine of the ten countries which present the highest rates of child marriage are considered to be fragile states, demonstrating the impacts of insecurity on the increase of this damaging practice. In this regard, the top 10 countries with the highest prevalence rates of child marriage – percentage of women 20-24 years old who were married or in union before they were 18 years old – are: Niger (76%), Central African Republic (68%), Chad (67%), Bangladesh (59%), Burkina Faso (52%), Mali (52%), South Sudan (52%), Guinea (51%), Mozambique (48%) and Somalia (45%).

child brides are more likely to be isolated from family and friends, to be excluded from participating in their communities and to have lower socioeconomic outcomes, trapping them in a cycle of poverty, gender inequality and disempowerment at all levels

Child marriage affects society and countries

The consequences of this harmful practice affect not only early and forced married children and their families but also society and countries, leading to a huge loss of their collective potential which impacts on every economy and workforce for generations. For this reason, credible and appropriate alternatives for preventing this harmful practice must be provided by the international community, governments, policymakers, civil society organisations, community leaders and other entities to families and children to prevent them from suffering this early and forced marriage.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the global COVID-19 pandemic also has devastating effects on child marriage survivors and the vulnerable girls and young women at risk of suffering this damaging practice. In this respect, this global health crisis is increasing poverty, insecurity, gender inequality and vulnerability and the widespread lockdowns of schools, shelters or girl’s centres and confinement measures may force girls to get back into serious situations which they had left behind.

It is absolutely necessary that we tackle the structural obstacles limiting gender equality and women’s economic, social and political empowerment in conflict-affected settings, post conflict and humanitarian contexts including the specific and mandatory target of protecting children, especially girls, from early and forced marriage. Child, early and forced marriage must be recognised as a critical issue in times of crises and it is indispensable to ensure girls’ access to education, healthcare, training for finding decent works, legal support, protection from gender-based violence and safe spaces.

There is no time to lose in ending child, early and forced marriage and to move towards the full achievement of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda.

Image credit: DFID – UK Department for International Development (CC BY 4.0)

Girls and women like Taketu (pictured) have the right to live free from violence, discrimination and early and forced marriage (CEFM) achieve their potential.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not necessarily reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.