This blog is based on research commissioned by the International Peace Institute. For a fuller account of the research and its findings see: At the Nexus of Participation and Protection: Protection-Related Barriers to Women’s Participation in Northern Ireland.

Catherine Turner and Aisling Swaine explore the intersection between women’s participation and protection in the context of Northern Ireland illustrating the tensions and connections between the two which not only highlight the continued relevance of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda, but also the need for it to engage with this tension on a more meaningful level.

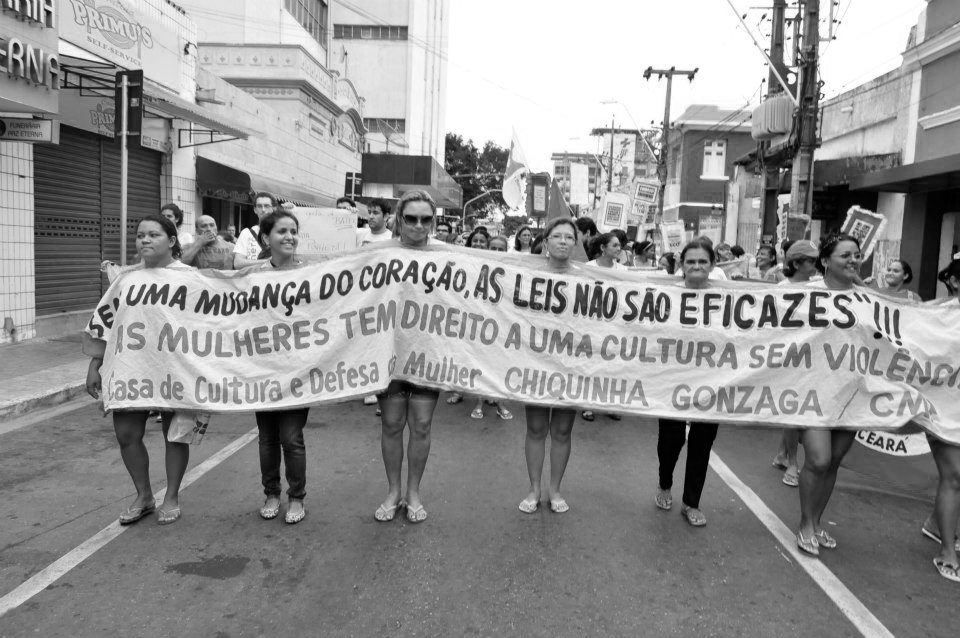

Of its four pillars, participation and protection arguably predominate the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda. Growing gaps in women’s leadership across all spheres, exacerbated by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, is at the fore of the 2021 Generation Equality Forum taking place this month. In the realm of peace and security, women’s leadership remains starkly unequal, despite significant efforts in global multi-level peace initiatives.

The WPS agenda’s expansion along two ‘participation’ and ‘protection’ tracks has meant that, over the last 20 years, these pillars have largely operated as separate spheres of activity. Efforts to increase women’s participation have largely coalesced around peace processes and the nexus between women’s participation and gender sensitive outcomes. The centring of protection concerns on violations of international law, has meant that protection has largely focused on conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) by armed actors. Some resolutions have importantly expanded language on the “security threats and protection challenges” that affect women. The ways that women’s leadership is obstructed by peace and security-related violence and threats, and its role in deterring women’s participation, has not been fully considered.

The predominant, yet partial, view of protection comes up against emerging evidence of the threats and risk faced by women peacebuilders and human rights defenders (HRDs). The most recent WPS resolution encouraged “Member States to create safe and enabling environments for civil society, including formal and informal community women leaders, women peacebuilders, political actors, and those who protect and promote human rights.” Congruent implementation of the protection and participation pillars across all aspects of the maintenance of peace and security, is now evidently needed.

Northern Ireland, 23 years post the 1998 Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, is a context that starkly illustrates the significance of the connections, as well as tensions, between women’s leadership and protection in conflict and post-conflict situations. On the basis of 25 interviews with women in leadership positions in Northern Ireland, we outline here critical protection risks and barriers that must be engaged with if women’s participation in this, and other similar contexts globally, is to be achieved.

Increased Threats with Increased Leadership

One of the starkest findings of the research is the extent to which women in leadership – from community sectors to public sectors such as policing, and in elected politics – experience and live with harassment, risk and threat as part of their everyday professional lives. Derogatory sexism intermingles with sectarianism, violent masculinities, and community polarisation directly resulting from the ‘Troubles’ to influence where and how women participate. In the research we found four main categories of risk that women have faced:

Direct physical threats

These include verbalised threats to women’s lives issued by paramilitaries, often through intermediaries. Women live daily with the risk of incendiary devices under cars, which is a known practice and part of the backdrop of violence that some respondents articulated as ‘a physical threat that is always there’.

Threats to their homes and families

There was a real sense of vulnerability of the home, with some women’s homes having been attacked. Women articulated fear of their home address being ‘known’, fear of physical attack on the home such as firing of missiles through windows, as well as graffiti posting their home address in public places as an implicit invitation to attack them. All of this serves to intimidate and instil fear and hinders women’s ability to freely go about their work.

Threats to workplaces

The women we spoke to all worked on an inclusive basis, meaning that they responded to the needs of all communities in their work. As a result, many women have had their workplaces attacked, including arson, and many feel that their work is subject to attempts to control and even intimidate them in their workplaces.

Public Shaming

Women were also subjected to attempts to discredit their professional reputations by questioning and making damaging insinuations on the basis of their sexual, reproductive and bodily integrity. For example, sexually explicit graffiti, messaging and images have been circulated both in physical spaces, such as on walls in the communities they worked in, and in online forums such as Twitter and Facebook. Social media emerged as a particularly threatening forum for generating social and collaborative attacks on women.

What we also observed was that the level of threat rose depending on the extent to which women were challenging existing power holders within their communities.

Derogatory sexism intermingles with sectarianism, violent masculinities, and community polarisation directly resulting from the ‘Troubles’ to influence where and how women participate.

A core theme across the broader research on women mediators and peacebuilders has been that women can often access mediation roles because they are seen as less threatening, and as less political than men. In some countries, including Northern Ireland, cultural taboos may mitigate the risk of direct physical violence against women peacebuilders.

However, this research found clearly that while women did play these intermediary roles with armed groups, they had to do so in covert ways. They felt that they existed in a ‘grey zone’ of risk whereby they were engaged in work that fell outside the scope of legal and policy protection, even while policies encouraged them to act in these roles. This heightened the level of precarity for them and for their work, and rather than ‘empowering’ women and women’s participation, it erodes the possibilities for safe public leadership on the part of women.

Circularity of Risk and Representation

Overall, the research revealed clear connections between low numbers of women participating in politics and public life – their exposure to risks – and the impact that this has on increasing women’s participation. It seems that increasing women’s participation was stuck in a vicious cycle whereby participation raised protection concerns, which in turn reduced incentives to participate. While it is often expected that women’s participation in political and public life, including in the security sector, will make these spaces safe for women, the research clearly showed that when women participate in small numbers, they lack the influence to make meaningful change on systemic barriers. Instead, they face threats and abuse that are designed to silence them and discourage more women from participating.

In Northern Ireland, gender inequalities and insecurities intersect with the legacy of political violence, repeated political crises and informal power contracts that benefit some over others arising from power-sharing arrangements under the peace agreement. These, in turn, intersect with emerging technologies such as social media. Public life for women becomes characterised by misogyny, threat and risk. In turn, this deters other women and new generations from getting involved.

This is the character and quality of “peace” that becomes accepted in multiple post-conflict contexts globally. It is clear that if women’s leadership is to be properly supported, WPS needs to move beyond ‘additive’ approaches and support for individual resilience and acknowledge and address the deeply systemic barriers that exist. While the WPS agenda is a critical tool for advancing women’s participation, it is evident that deeper engagement with the roots of structural inequalities, sexism and misogyny, and with gendered protection concerns that arise as a result, is required if the agenda is to substantively advance women’s equality and participation in the longer term.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not necessarily reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.

Image credit: UN Women (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)