How an adapted ‘business model canvass’ may help.

Image credits: Abhi Sharma / Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Every researcher and academic is like a one-person ‘start-up company’ to begin with, especially during their doctorate and possibly into their early post-doc phase. Indeed, perhaps researchers are always, at root, alone, having to make research choices for themselves that are also always life choices, normally with substantial career-path implications.

Some STEM science PhDs and early career researchers, may disagree that they control significant choices. They might point out that their research topic has been assigned to them by their professor or supervisor; that they are working every day as a cog in a larger lab team (where their efforts may often be partly diverted to remoter topics); and that they often feel that their academic prospects depend as critically on the lab leader’s reputation, academic weight and decisions as on their own efforts. If this sounds like your situation, it would be easy to feel only a kind of hived-off or partially independent branch company of the principal investigator’s larger research team. Yet in the end, none of these features (or effort to fit in with them) guarantees a position. To stay in academia, even the most team-based PhD or post doc must define their own career trajectory. Being just a loyal delegate or lieutenant to a senior prof, rarely leads anywhere great in university STEM science — you still have to show academic independence and self-direction. Finally, of course, many PhDs and ECRs in STEM subjects continue their research and careers outside academia. But even in these more externally structured settings, key Janus-faced research/career choices remain, and with them the need to evaluate your own path.

Meanwhile, over in the humanities and social sciences, many researchers (indeed most academics in some areas) remain a one-person enterprise (‘lone scholars’) throughout their entire careers. Their co-authoring is rare or evanescent. The PhD students they supervise work on other topics that they largely choose and define themselves. And lone scholars often acquire no followers or disciplines. By contrast, most researchers in the STEM sciences, and some in social science, merge and amalgamate their efforts in permanent or recurring co-authoring teams, that endure and tackle more complex projects in a labour-sharing way. Some academics build medium size research teams, and others enter really large-scale projects and programmes of work.

Applying the ‘business model canvass’

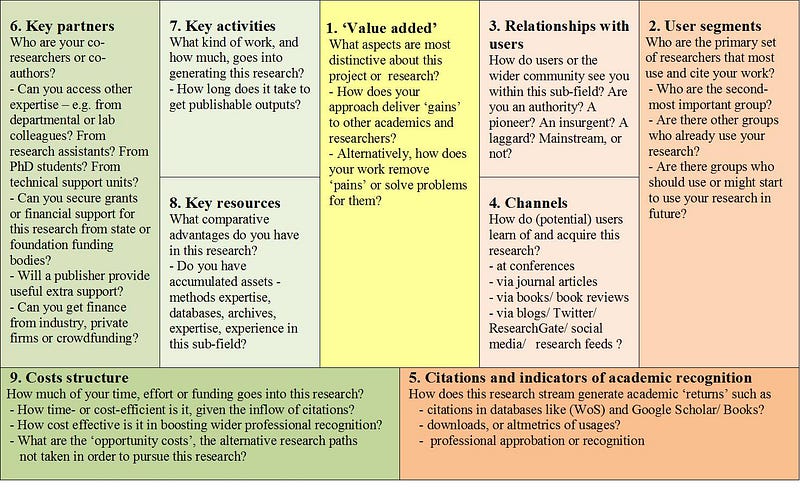

Whatever your field and stage of career, an analytic framework developed for start-up firms, called the ‘business model canvass’, may help academics or researchers in thinking about and evaluating their choices around committing to a given stream of research. My chart below shows how this approach can be adapted to the academic context, and used to assess the pluses and minuses, the likely ‘returns’ and risks, of investing in different projects or streams of research, when those decisions also define a career pathway.

The business model canvass applied to choices in academia

In the center of the chart (box 1) is what a business school analyst would call ‘the value proposition’ of this stream of research — that is, the way in which a product or service either adds positively to the welfare or happiness of consumers, or removes or helps to simplify or reduce a problem or impediment that consumers experience.

Framing the point in this fashion is useful in business, because it forces entrepreneurs or would-be innovators to stop thinking about their brilliant product from a supply-side perspective, and instead to start looking at it relentlessly at from the demand-side. The same shift has virtues for academics, because it makes us focus attention on what exactly a research stream will contribute to the practical life of our discipline or sub-field. Sometimes this contribution goes unappreciated by, or is rejected by, academic colleagues for a time, before securing delayed recognition (the quite common phenomenon of ‘incubated impact’). Sometimes too, however, you make a commitment, betting on later recognition that never in fact comes. The research you ‘invested’ in instead defines only a lonely backwater, or becomes like a Wikipedia ‘stub’ entry, something that never gets picked up on or further elaborated.

Yet so long as the researcher herself can identify what value-added contribution is being made, there may still be a strong case for persevering. In academia, institutions (not people) do the remembering and the forgetting, in a fashion that Mary Douglas stresses is true of all social life. Fear of one’s research not being taken up, leading to a blind ‘herding instinct’ following of currently popular topics, can be as futile in academic life as a mob of primary school footballers forever chasing after a soccer ball, with no concept of marking or positioning.

Yet, wherever you see your research avenue leading, it is also important to specifically identify who the users of the research are, or should be if they were more receptive (box 2 in my chart). Predicting in a dynamic field is tricky, but don’t sit content with an overly generalized view. Can you picture, in detail, the ‘users’ of the research and the contexts they operate in? With the modern emphasis on achieving external impacts from academic work, and the lowered costs opened up by social media, remember to consider ‘practitioner’ impacts as well.

Box 3 here suggests that you go further, to consider how these communities characterize your contribution — because once your academic reputation congeals, and your CV and citations profile takes on a certain clear character, it can be hard to break out of or to change such professional judgments. Moving fields or sub-fields later on, to add on or emigrate to different topics or strands of research, is easiest in the humanities and more qualitative social sciences, and hardest in STEM fields and quantitative social science. Changing a research ‘style’ or approach is easiest perhaps at post-doc stage (helped by youthful enthusiasm and can-do spirit) or in mid career (helped by cumulated experience). But it also tends to depend a lot on getting a grant to cover the lengthier timescales that changing fields or topics involves.

The specific channels of communication by which users or potential users can find out about your research are worth itemizing (box 4). Don’t just assume that the previous, ages-old trinity of channels — seminars/working papers, conferences, and journals or books (depending on discipline) — still works for you. Modern science communication and academic networking repertoires have expanded sharply recently. New digital alternatives — including research databases, online depositories and academic blogs — are less reliant on mediation by other people. They reflect your own energies and capabilities in not being an academic hermit, but instead ‘pushing’ materials out, in accessible formats — discussed in some of my other blogposts.

The final element on the right hand side of the canvass is box 5, which asks what academic return (what ‘revenue’ in business terms) does a research project generate, or might it generate in future? How many citations does it create already for you, or might it create in future, measured perhaps both realistically and hopefully (at a maximum)? And if not citations, are there alternative indicators that this work is well-regarded and making a positive contribution to your professional standing? These cues might include altmetrics and usage statistics, fast indications of future citations seedcorn. Or they might be approval in professional circles, or endorsements in government/official audits (like the REF process in the UK or the ERA in Australia)? Perhaps materials that attract few readers or citers may none the less elicit a positive reception in university promotion boards, or professional or academic elite academies, many of which sometimes seem to value highly esoteric research that no one reads. (By contrast, simply getting a piece of hard-boiled and inaccessible research into a ‘top’ journal, only for it to be neglected by the rest of the discipline thereafter, is a pointless activity — and may even detract from your CV).

Turning to the left-hand side of the canvass, the focus shifts to what is used up, or lost for good, in pursuing a particular project or stream of work. What specific activities are involved in developing it (box 6) in terms of lab work and experiments, fieldwork, archival research, library work, running data analyses, and allocating time to theorizing, writing/re-writing, and publishing? Offsetting this may be key resources (box 7), such as a comparative advantage in terms of methods, theory grip or theme; or a track record of previous work in the sub-field. Contributions by co-authors, other members of the research team, research assistants, PhD students or post-grads (and the finance needed to support them) can all make a difference (box 8), as well as wider or more diffuse support from your department or lab. Outside of intensive teams in labs, or socially close-knit sections of departments, the critical inputs or contributory expertise of colleagues may seem very episodic, or elusively ephemeral — a ‘climatic’ influence akin to how the weather shapes your moods. But the salience of stimuli from colleagues in seminars or conferences in re-steering your efforts or helping overcome blocks is still considerable.

These right-hand side considerations cumulate in an overall assessment of the costs of this project or stream of work (box 9), to set against its returns. How time-consuming or effort-intensive is the amount of work needed to generate a flow of publications? What are the realistically-assessed risks and‘opportunity costs’ of following this line of work, in terms of foreclosing other research options and pathways that might be open to you?

Assessing the components of your portfolio effectively means bearing in mind the difficulties of predicting which article or publications will be successful or not; the general difficulties of attracting citations; and the need if possible to avoid adding to the‘tail’ of relatively unsuccessful or uncited publications that most of us have. In the STEM disciplines the prevailing ‘mono-culture’ of journal articles means that there is often no great need to consider what to write, although where to send papers is more difficult. Rather rarely perhaps, more senior academics in STEM subjects may consider writing a textbook, a research or intermediate-text book for professionals, or even a ‘pop science’ book in their area. For STEm scientists the key decisions will mostly tend to revolve around involvements in different research projects, mostly with co-researchers or teams — where the prospects for research to be successful may be correspondingly harder to assess, and a lot will rest on colleagues.

By contrast, in many social sciences, and all the humanities, academics will need to consider how to best distribute their efforts across a more varied palette of journal articles, chapters in books, research books, intermediate texts and textbooks. A few especially talented or lucky authors may also consider if they can achieve ‘mass public’ books within their mix of outputs.

How you implement this academic version of the ‘business model canvass’ framework will depend a lot on what stage your career is at, what critical masses of publications you need to assure your livelihood and position, and what constitute the ‘right’ publications in your discipline. These considerations make any generic advice-giving farmore complex. But actually, for an individual researcher, choosing at a defined point in their career, these are all simplifying factors. You know your own competences and your field well already — in fact you know more about your competencies than anyone else in the world. But

- ‘knowing yourself’ without self-deception

- ‘knowing your field’ without ‘optimism bias’ and other obstructions to clear vision;

- locating this knowledge in a constantly moving (sometimes disruptively changing) intellectual landscape; so as to

- undertake specific actions to realize optimal (‘best that can be done from here’) results,

- in a robust or sustainable way

are all psychologically difficult things to grapple with. Here’s where this relatively simple but systematic frame of organizing ideas and considerations may be some help.

I’d welcome comments, critiques or alternative suggestions via email to: p.dunleavy@lse.ac.uk. For new update materials please see my Twitter account @Write4Research and the many diverse contributions on the LSE’s Impact blog.