The Palace of Westminster Restoration and Renewal Programme is faced with a fundamental question: how can the Houses of Parliament, a purpose-built building from the mid-nineteenth century, be transformed to meet modern standards? Henrik Schoenefeldt writes that, although requirements have changed, history offers an opportunity to reflect on how politicians were previously involved in the design of Parliament.

The Palace of Westminster Restoration and Renewal Programme is faced with a fundamental question: how can the Houses of Parliament, a purpose-built building from the mid-nineteenth century, be transformed to meet modern standards? Henrik Schoenefeldt writes that, although requirements have changed, history offers an opportunity to reflect on how politicians were previously involved in the design of Parliament.

‘We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us’. These famous words by Winston Churchill were part of a House of Commons speech on 28 October 1943, in which he advocated a reconstruction of Charles Barry’s original House of Commons debating chamber. Completed in 1852, the building was destroyed by the Luftwaffe in 1941. It is not clear if Churchill was aware of the process used in the design of that chamber, but 19th century politicians played an active role in shaping their working environment. Its design was the outcome of a slow and complex process lasting over fifteen years. A major contributor to this complexity was precisely this direct involvement of Parliament, including the invited (and uninvited) involvement of parliamentarians that ranged from user consultations to full parliamentary inquiries instigated by dissatisfied Members. Although this experimental approach was disruptive, time-consuming, and expensive, it represented an early example of participatory design.

Politicians shaping architecture: the consultations

Charles Barry and Augustus Pugin’s architectural scheme was formally announced as the winner of a competition to redesign the Palace in February 1836. The scheme, signed off by the Commissioners at the end of this process, was a simple block-plan only outlining ‘leading principles’. The design brief and programme had also not been fully developed. After 1836 Barry himself took the initiative to develop a deeper insight into the requirements of parliament by interviewing heads of various departments, such as the Sergeant-at-Arms, Clerk of House of Commons, and Speaker – Barry saw interviews as an effective method for acquiring knowledge of what a modern parliament building requires.

But this level of political involvement also posed significant challenges from a project-management perspective. A critical review of Barry’s working practice, conducted by Select Committees of both Houses in 1844 and 1846, revealed that its impact had not been anticipated. There was neither a formal process of approval for plans nor a single authority in charge of monitoring and authorising design changes. The Commissioners of Woods and Forests – the government department responsible for parliamentary building projects – did not monitor or interfere with Barry’s work, arguing that, not being architects or engineers, they were not qualified to evaluate the work. Due to the unauthorised design decisions, delays, and cost increases an independent client body, the ‘Commission for Superintending the Completion of the Houses of Parliament’ was finally appointed in 1848.

Credit: Pixabay/Public Domain.

Credit: Pixabay/Public Domain.

Politicians shaping architecture: participation in experimental inquiries

In addition to consultations, Members were involved in experimental inquiries. Numerous design questions, such as the arrangement of benches, galleries or ventilation, were investigated empirically. Barry also consulted the Speaker and Sergeant-at-Arms on the internal arrangements of the chamber, and worked with individual MPs on possible seating configurations, while alternative configurations were tested in a series of trial debates with full-scale mock-ups. The trial debates also revealed, for the first time, that the acoustic of the interior was unsuitable for speech, which, although a central functional requirement, had not received any serious consideration. A parliamentary committee consulted scientific advisors on acoustic design and further trial sittings were held, during which members assessed the effects on acoustic quality.

But the most extensive level of Member engagement was in the context of ventilation and climate control. The Temporary Houses of Parliament, erected by Robert Smirke after the Great Fire of 1834, was used for field studies on ventilation, climate control, lighting, and acoustic. A detailed study of these inquiries published in Architectural History, shows that the physician David Boswell Reid convened extensive experimental inquiries on ventilation between 1835 and 1851.

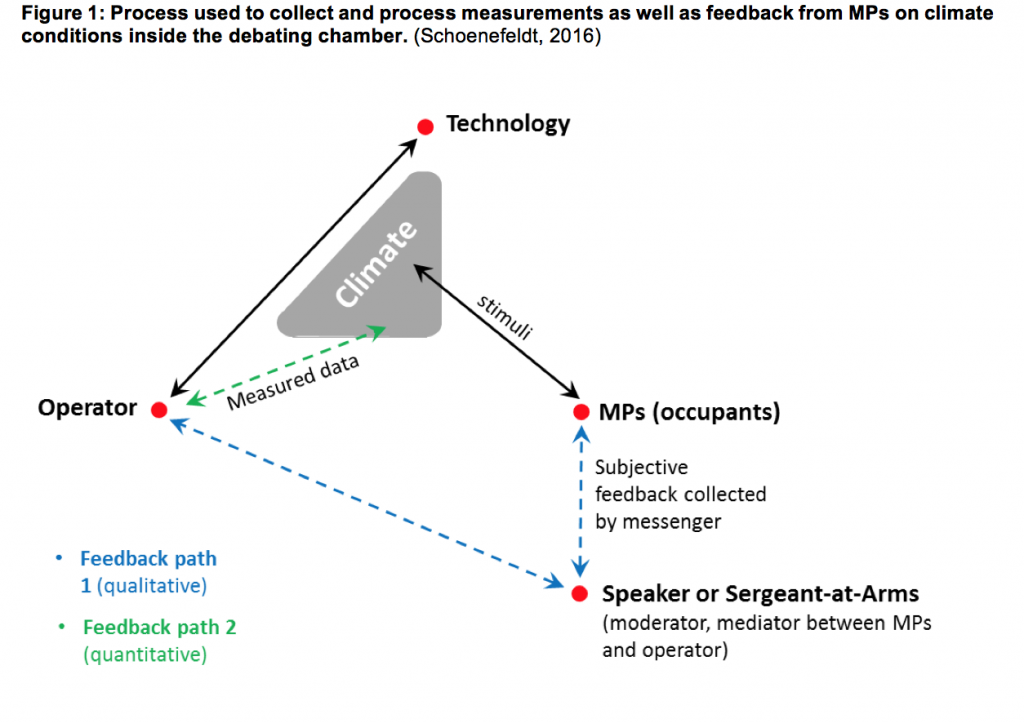

In these field studies, MPs provided feedback on the system’s performance, focusing on the quality of experience. Reid introduced a formal process of collecting and processing personal feedback from Members – as the perception of climate and air purity is highly subjective, feedback was often conflicting and had to be moderated by the Speaker or Sergeant-at-Arms before instructions for changes were sent to the operators.

These inquiries have closer resemblance to the qualitative research undertaken within the social sciences than traditional engineering design with its technical focus. New insights gained through this involvement of Members fed into the design of a new system for the House of Commons, through which Reid hoped to respond to users’ personal experiences. (For more on this process, see here and here).

After the completion of the new building, politicians continued their role as design critics, using complaints to improve the design. But the new system did not succeed in satisfying expectations. Between 1852 and 1854, the House of Commons appointed several committees to review the system’s performance, involving both interviews with users and scientific studies conducted by external consultants. Issues, however, were never fully resolved and in response to increasing pressures from Members, it was re-modelled to follow a different approach to ventilation.

From a reactive to a coordinated approach

MPs were building users who used their power and financial resources to shape their working environment. Much of their involvement was in the form of unplanned interferences, ranging from individual complaints, to debates and formal inquiries coordinated by Select Committees. As such, it followed a reactive approach to user engagement, which had been highly disruptive. Yet the more planned efforts – such as the empirical testing of seating configurations – also illuminate the potential of such involvement to aid the advancement of design from a user-experience perspective. This can only succeed if a clear methodological framework is adopted that follows a carefully curated engagement programme. Establishing an engagement framework will undoubtedly become critical in the forthcoming refurbishment and more recent projects, such as the Scottish Parliament or the UN’s Capital Masterplan, also illustrate that the issues faced in the 19th century remain very relevant.

______

Note: The above builds on a paper presented at the roundtable discussion ‘Designing for Democracy: The role of architecture and design in parliamentary buildings,‘ which was held at the Political Studies Association Conference in April 2017.

Henrik Schoenefeldt is Senior Lecturer in Sustainable Architecture at the University of Kent and an AHRC Leadership Fellow. He is currently on a two-year secondment to the Palace of Westminster Restoration and Renewal Programme to lead the research project ‘Between Heritage and Sustainability – Restoring the Houses of Parliament nineteenth-century ventilation system.‘ His most recent publications on the topic include a chapter in Gothic Revival Worldwide, and a forthcoming article in the Journal of the Society of Antiquaries entitled ‘The Historic Ventilation System of the House of Commons, 1840-52: revisiting David Boswell Reid’s environmental legacy.

Henrik Schoenefeldt is Senior Lecturer in Sustainable Architecture at the University of Kent and an AHRC Leadership Fellow. He is currently on a two-year secondment to the Palace of Westminster Restoration and Renewal Programme to lead the research project ‘Between Heritage and Sustainability – Restoring the Houses of Parliament nineteenth-century ventilation system.‘ His most recent publications on the topic include a chapter in Gothic Revival Worldwide, and a forthcoming article in the Journal of the Society of Antiquaries entitled ‘The Historic Ventilation System of the House of Commons, 1840-52: revisiting David Boswell Reid’s environmental legacy.