As the 2015 general election draws closer, there is an increasing shift away from the politics of co-operation between the coalition partners to the politics of electoral positioning. This is an especially difficult task for the Liberal Democrats, who have had a pretty miserable time delivering on their manifesto pledges and whose successes have been appropriated by the Tories. Nevertheless, Craig Johnson does see a distinct possibility that the Liberal Democrats will win enough seats in 2015 to hold the balance of power yet again

As the 2015 general election draws closer, there is an increasing shift away from the politics of co-operation between the coalition partners to the politics of electoral positioning. This is an especially difficult task for the Liberal Democrats, who have had a pretty miserable time delivering on their manifesto pledges and whose successes have been appropriated by the Tories. Nevertheless, Craig Johnson does see a distinct possibility that the Liberal Democrats will win enough seats in 2015 to hold the balance of power yet again

We’re now less than a year away from the next UK general election. For psephologists and fellow political anoraks, this has been made much more exciting by a spate of opinion polls and polling predictions. This week, two such polls have revealed small leads for the Conservatives. Of course, these should be treated with caution. Polls are a guide, and a limited one at that, but they still provide some good news for the Conservatives. Labour’s lead has steadily fallen for over a year, and David Cameron’s party will be perhaps happier with the long term trend than they once were, but what about the coalition as a whole?

As the first peace-time coalition draws to an end, for the two parties there is an increasing shift away from the politics of co-operation in the rose garden to the politics of electoral positioning. Despite Michael Gove’s repeatedly spirited defence of free schools, it does not mask the split within the education department between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. It marks an increasing number of differences between the two parties throughout government. This is not terribly surprising. Each party must defend the overall performance of the coalition whilst at the same time articulating some sense of distinct values.

This is tricky for both parties, but especially so for the Liberal Democrats. Many of the primary goals of the coalition have been largely at the insistence of the Conservatives, such as deficit reduction, NHS and welfare reform, and steps to reduce immigration. Any Liberal Democrat policy ‘wins’ appear to have been successfully claimed by the Conservatives, with the increased income tax threshold the prime example. Paun and Munro set out five lessons for the Liberal Democrats in dealing with this problem.

In part, the Liberal Democrats’ problems go back to the coalition negotiations of May 2010. Tim Bale delightfully argues that ‘the coalition agreement between the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives shows what happens when vegetarians negotiate with carnivores’. The Liberal Democrats obtained none of the big offices of state, nor did they have any definite control of any department where they might implement their manifesto commitments.

The four key themes running through their 2010 manifesto were fair taxes, fair chances for children, green investment, and cleaning up politics. On fair taxes, their key pledge to raise the income tax allowance has been implemented, but only incrementally. At the same time, however, the rate of VAT has been raised; something the party campaigned against in 2010. The key pledge of ‘fair chances for children’ was the ‘pupil premium’, which has only been funded via education budget cuts elsewhere. On the environment, based on a YouGov/GreenPeace poll in March 2012, only 2 per cent of the country believed David Cameron’s statement from 2010 that his government would be ‘the greenest ever’. Accounting only for Liberal Democrat voters, this figure reduces to 0 per cent. Finally, and perhaps most importantly for the party, on the issue of ‘cleaning up politics’ the party has fundamentally failed on its promises from 2010. At a ratio of more than 2:1, the public voted against electoral reform, and even that reform would have been, in Nick Clegg’s own words, a ‘miserable little compromise’. Plans to reform the House of Lords have been dropped, no real progress has been made on party funding, and a statutory register of lobbyists remains ‘in progress’.

For the next year then, the Liberal Democrats have a challenge to articulate their own policies and values without appearing to go back on what they have previously argued. Wager suggests that this year will see the deliberate wobbling of the yellow-blue jelly that is the coalition. Whilst the Liberal Democrats’ national poll remains stubbornly low, it is not all doom and gloom. The Liberal Democrats’ electoral success next year will also depend on their ability to maintain their strength where they already have MPs. So far, it seems that they are doing that to the extent that they may be able to somewhat mitigate national poll losses.

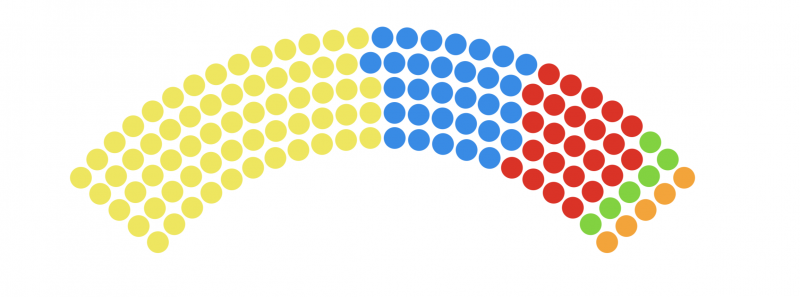

The prospects for the Liberal Democrats do not look immediately rosy, and in essence, whether or not they remain in government next year is not in their own hands. However, as in 2010, the Liberal Democrats could themselves have a disappointing election and still win power. Predictions still suggest a hung parliament. Indeed, it is perfectly possible that Conservatives could win more votes but fewer seats than Labour, that UKIP could outpoll the Liberal Democrats yet not win a single seat, and that the Liberal Democrats win enough to hold the balance of power yet again. The test for the Liberal Democrats is to articulate as much of their own agenda beforehand whilst still supporting the overall framework of the coalition.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Craig Johnson is a PhD student in Politics at Newcastle University. The full results and his analysis of Liberal Democrat associations is available to read in Politics (open access). He tweets at@cjnu1 and blogs here.

Craig Johnson is a PhD student in Politics at Newcastle University. The full results and his analysis of Liberal Democrat associations is available to read in Politics (open access). He tweets at@cjnu1 and blogs here.