British political parties are highly cohesive on most divisions in the House of Commons – including on free votes. Christopher D. Raymond and Robert M. Worth explain why party loyalty is therefore independent of party discipline and shared preferences.

While the storied notion of British political parties in the House of Commons as highly disciplined has been challenged in recent years, parties remain highly cohesive on most divisions. Even on free votes, on which MPs are formally released to vote independently of their parties, MPs often continue to vote along party lines. If these votes are not entirely idiosyncratic – e.g. in terms of the forces motivating the vote or the issues decided – then examining the behaviour of MPs on free votes that are genuinely free offers us an interesting opportunity to look into the factors supporting party cohesion.

Three Explanations of Intra-Party Cohesion

In our forthcoming article in British Politics, we examined the possibility MPs are motivated to vote along party lines out of a sense of loyalty. Drawing from previous research arguing that MPs have psychological ties to their parties that lead them to behave in ways that favour their in-group and work against out-groups, we seek to replicate a test of this argument applied in previous research. If MPs continue to vote along party lines after controlling for alternative explanations of party cohesion, this would provide at least some support to this party loyalty argument.

One of the advantages of examining free votes is that if MPs are genuinely free to break with their parties, we can rule out one of the alternative explanations of party loyalty as an explanation for any observed cohesion: party discipline enforced by the whips. In this case, we observe MPs’ voting behaviour on four divisions related to the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 and the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 2000 seeking to standardise age-of-consent laws – in order to prevent discrimination against homosexual males. Because parties remained cohesive on these four divisions, and because we found that MPs were genuinely free to vote as they preferred on these divisions, we rule out whip-based discipline as the reason for the observed cohesion on these votes.

We also account for a second alternative explanation of party cohesion: that MPs of the same party voted together due to shared preferences (e.g. socially conservative MPs, drawn largely from the Conservative Party, voting against standardising age-of-consent laws). To account for the impact of MPs’ preferences, we used responses to the British Representation Survey, 1997, which was a representative survey of candidates conducted during the 1997 general election campaign. Specifically, we create a social conservatism scale based on attitudes towards issues of traditional morality, including same-sex marriage attitudes. If MPs continue to vote along party lines after accounting for differences in preferences, this would provide evidence that party loyalties also impacted MPs’ voting behaviour.

Findings

To determine whether there was any evidence of an independent party loyalty effect, we estimated the impact of a variable measuring Conservative MPs on the likelihood of supporting the standardising of age-of-consent laws on each division as a binary variable using logistic regression. If this Conservative Party variable remains statistically significant after controlling for variables measuring the preferences described above, and after controlling for several other characteristics – MPs’ religious service attendance, left-right ideology, gender, education, and the percentage of Christians in their constituencies – then this would provide evidence to suggest Conservatives continued to vote cohesively in part out of a sense of loyalty to the party that is independent of party discipline effects and shared preferences.

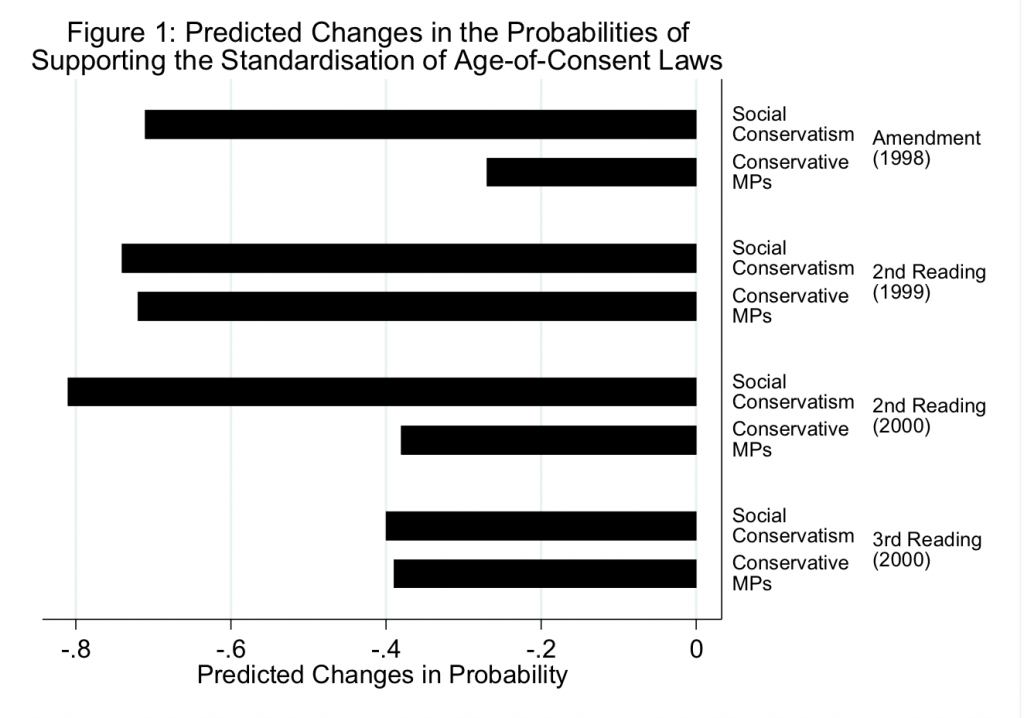

Figure 1 presents the predicted changes in probabilities for the social conservatism and Conservative Party variables when moving from the lowest to highest values (holding all other variables at their medians). We see that while socially conservative MPs were considerably less likely to support standardising age-of-consent laws, Conservative MPs were also significantly less likely to support these bills. On two of these divisions – second reading of the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act in 1999 and third reading – the estimated change in probability due to the Conservative Party variable rivals the estimated effect of preferences. Thus, in addition to suggesting that party loyalties impact MPs’ voting behaviour independently of shared preferences, these results suggest the party loyalty effect may be sizeable as well.

Implications

Our analysis suggests party loyalties that are independent of the two main explanations of party cohesion impact MPs’ voting behaviour. That being said, there are two important limitations to these findings. One is that the evidence of party loyalty effects on voting behaviour is less direct than we would desire. Though the research design largely rules out formal discipline and shared preferences as explanations for the residual party cohesion observed on these free votes, more effort will be needed in future research to measure party loyalties directly (so as to rule out hitherto unexplored explanations for these findings).

Additionally, the fact these four divisions were decided as free votes makes generalisation to most other divisions (especially those that are whipped) problematic given the possible selection biases associated with examining free votes – which may result in stronger party loyalty effects on free votes than would be observed on most divisions. Thus, additional research exploring whether party loyalties impact voting behaviour on whipped divisions – and dealing with other issues – is needed to confirm the findings presented in our article.

Despite these limitations, the fact we find evidence party loyalties independently foster party cohesion means future research will have to account for this possibility when examining MPs’ voting behaviour. If validated by future research, our findings would have important implications for how we understand political parties, as well as the cohesion within and the competition between parties. These findings would suggest that at some level (to be stated more precisely in future research), MPs stick together and oppose MPs from other parties due simply to the fact they belong to different parties. If true, this would necessitate that we consider how these group-based dynamics create challenges for policymaking – as well as institutional mechanisms to handle such partisanship.

____

Note: the above draws on the authors’ article in British Politics.

Christopher D. Raymond is Lecturer in Politics at Queen’s University Belfast.

Christopher D. Raymond is Lecturer in Politics at Queen’s University Belfast.

Robert M. Worth is a PhD candidate at the University of New Orleans.