The 2017 election saw a stronger than foreseen performance by the Labour Party. Matt Walsh explains how Labour’s Facebook success played out, heralding the party’s overall campaign performance. GE2017 was a numbers game: by achieving very high levels of organic reach, Labour managed to target undecided voters in marginal constituencies, energise voters who had drifted away from the party, and mobilise the young.

The 2017 election saw a stronger than foreseen performance by the Labour Party. Matt Walsh explains how Labour’s Facebook success played out, heralding the party’s overall campaign performance. GE2017 was a numbers game: by achieving very high levels of organic reach, Labour managed to target undecided voters in marginal constituencies, energise voters who had drifted away from the party, and mobilise the young.

Ever since last summer’s General Election journalists and academics have grappled with two key questions – why did Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party do so well; and why didn’t we see it coming? The answer, at least to the second part, is that most pollsters, journalists, and academics were looking for answers in the wrong places.

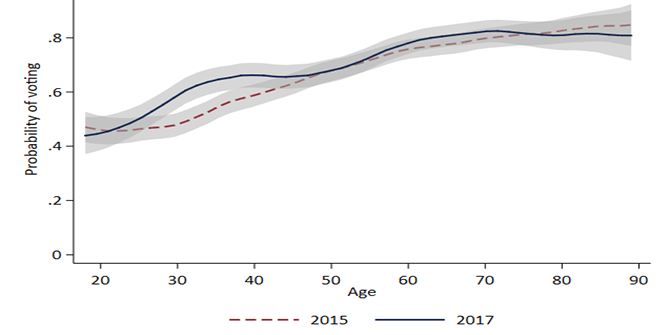

Received wisdom was presented as incontrovertible fact. Whether it was about campaigns making little difference to election results, the young not turning out, or the difficulty of winning from the left, the commentariat was wrong-footed in 2017. But going back to July 2016, the New Statesman’s Helen Lewis wrote of Jeremy Corbyn: “there is one place where he is unambiguously winning: Facebook”. She was right, and 2017 was unambiguously a Facebook election.

The sheer number of people following Jeremy Corbyn or the Labour party’s Facebook posts meant that the party was able to achieve very high levels of organic reach. That’s important because, in the 2015 election, the winning Facebook strategy was targeting undecided voters in marginal constituencies. In 2017, it was a numbers game. The first indicator that the tectonic plates were shifting was the number of followers party leaders and party accounts were reaching.

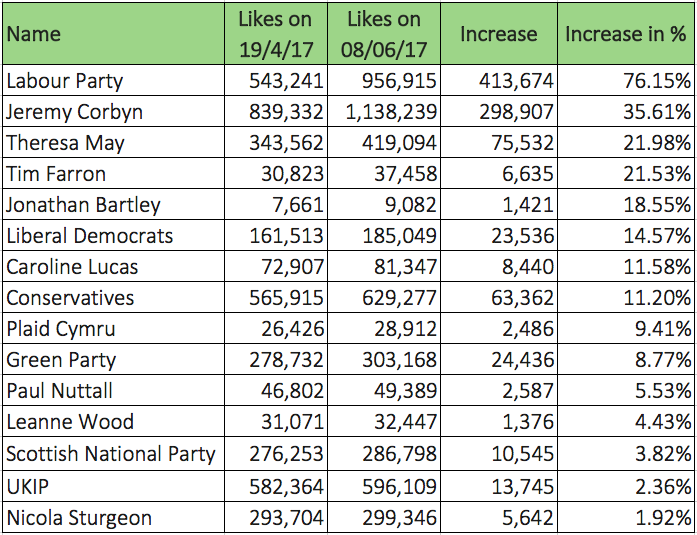

Table 1. Change in Facebook likes during the campaign

Table 1 shows the dramatic growth in Facebook likes for Jeremy Corbyn, up by more than 35%, and the Labour Party, up 71%, during the short campaign. This is despite a strong starting position at the beginning of the campaign. While there was growth for all the parties and leaders, it is notable that the performance of Labour and Corbyn considerably outstripped their rivals: the Conservatives, for example, rose 11%, and Theresa May gained less than 22%. The table also suggests that UKIP’s digital penetration had stalled. Despite starting as the most popular party account, by the end of the campaign, both Labour and the Conservative accounts had surpassed it.

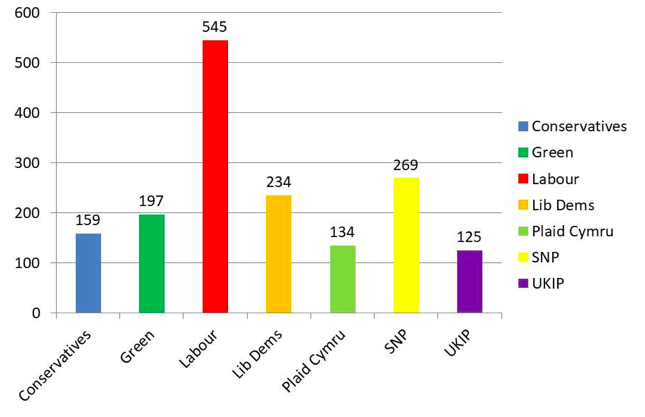

But it wasn’t just the number of people looking at the content: it was the amount of content being produced. Figure 2 records the number of posts by parties between Theresa May’s announcement of the General Election on the 18 April and polls closing on the 8 June. Labour was clearly the most prolific Facebook campaigner, and Corbyn’s individual account also paints a similar picture.

Figure 1. Facebook posts across the campaign

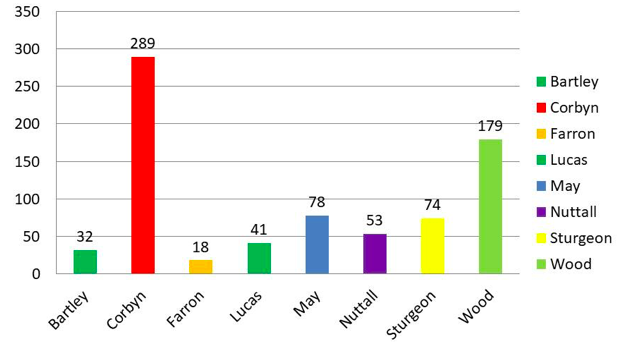

Figure 2. Facebook posts by party leader

The Labour party simply produced more content than its competitors, it posted more frequently and the content was more engaging. According to the content analytics company, News Whip, in the month leading up to the vote, the Labour page pulled in 2.56 million engagements on 450 posts, while the Conservative page saw 1.07 million interactions on 116 posts. Unlike the other parties, Labour repeatedly reposted material that had proved successful, rather than merely posting once on a topic and moving on. This meant that in total just 35% of Labour’s 545 posts were original, whereas 65% of them were reposts. By doing this, the party was able to ensure that the best pieces of content were viewed by the greatest possible number of voters.

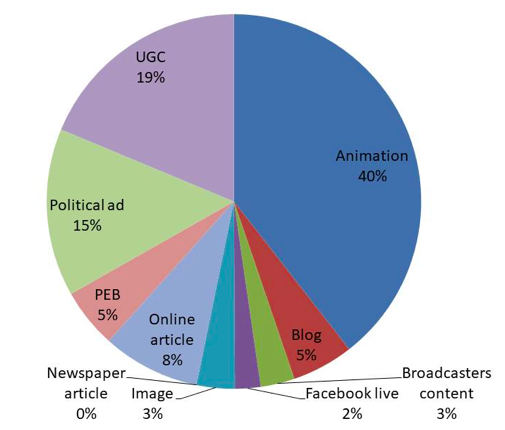

The difference in the types of posts is also instructive. While all parties showed an understanding of the importance of video content in successful political communications, Labour was able to create more and better quality content. Labour party election strategists had two clear drivers for digital media strategy. Firstly, they believed that when voters saw Jeremy Corbyn unfiltered by the perceived biases of the media, they would find him an engaging and sympathetic figure. To that end, much of the focus during the campaign posts was on Corbyn as a leader and on his personality.

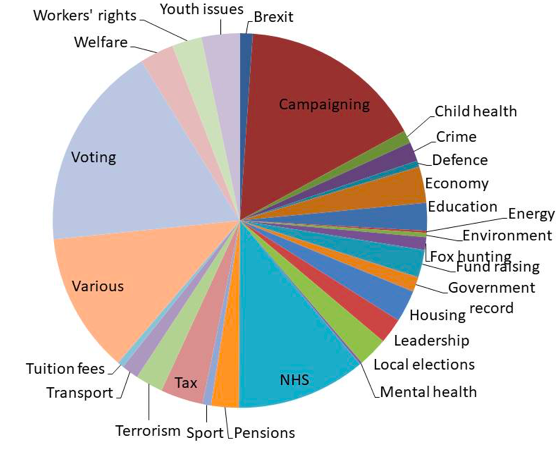

The second ambition was to counter negative reporting of Labour’s policy positions. The Labour communications team took the view that they had to aggressively counter the media’s framing of their policies. As such, a significant proportion of the Labour party posts were animations that explained policy positions on topics such as student tuition fees or the NHS.

Figure 3. Labour posts by media type. N=545

Figure 4. Labour posts by policy area. N=545

The Labour party’s Facebook feed spent a lot of time on issues connected to its campaign and voting. Labour strategists wanted to energise voters who had drifted away from the party since 1997’s New Labour landslide. Either by voting for other left-wing parties such as the Greens, or because they had stopped voting altogether. They were confident the campaign and Jeremy Corbyn could energise younger voters, whose turnout had steadily declined since the 1990s.

So, a significant proportion of the Facebook posts were dedicated to encouraging people to register to vote, celebrity endorsements of Labour, and campaign activity by Jeremy Corbyn. Events and speeches were planned in many safe Labour seats and Corbyn was given a hero’s welcome at events in places such as Tranmere. Sceptics suggested he was preaching to the converted but videos of these events built into a powerful narrative of a social movement gaining widespread popular support. A Facebook live video of the 6th of June Corbyn election event in Birmingham featuring the comic actor Steve Coogan and the dance act Clean Bandit was watched an astonishing 2.3 million times by the time polls closed. The aggressive use of feel-good videos, policy explainers, and shareable media helped drive forward the Labour party’s social media strategy.

There were two other significant factors that also helped support the Labour campaign on Facebook and both were from political actors that sat outside the party’s traditional structure. The first was Momentum, the campaign group that had grown out of a youth-focused support group for Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership bid. Having fought two leadership elections in two years, it had developed a strong sense of how to use social media, and video in particular, to deliver positive messages with viral attributes. Humour was a key tool, triggering an emotional response that made the content more shareable.

With 24,000 activists across the country, Momentum was able to mobilise support for Labour in previously hard-to-reach environments, such as southern cities with large student populations: in Canterbury, Labour returned its first-ever parliamentarian. According to the Momentum activist Adam Peggs, during the final week of the election the group’s Facebook videos were watched more than 23 million times by 12.7 million unique users. A significant part of this was due to the ‘Dad, do you hate me?’ film, which was watched around 7 million times in the final week of the campaign.

Momentum also had significant social media impact in areas Labour needed to win, including Cardiff, Derby, Sheffield, Canterbury and Plymouth. In the final week of the election, the group says 42.2% of Facebook users in Canterbury viewed its videos, while in Sheffield Hallam, where the former Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg was unceremoniously ejected by a Labour candidate, the percentage was 55.9%.

The other significant factor in Labour’s success was the growth of hyper-partisan political blogs. Sites such as The Canary, Another Angry Voice and the London Economic presented a relentlessly positive view of Jeremy Corbyn, an irredeemably damning view of his opponents, both outside and inside the party, and an intensely hostile view of the mainstream media. While partisan political blogging is not new, the new hyper-partisan sites have achieved a level of success outside the wonkish circles of their forebears. As pointed out by Buzzfeed’s Jim Waterson, the use of graphics, clear and understandable writing and consistent tone often mirrors the tabloid press they hold in such contempt.

So why did the Labour party do so well? In part, it was because Labour outperformed other parties on Facebook. More content was produced by the party and its supporters, and it generated more engagement with Facebook users than its rivals. It galvanised voters online and offline, supported by radical media and activist groups. The strategy of promoting Jeremy Corbyn and his policies successfully engaged voters, including the youngest, who had not voted in a General Election in such large numbers since 1992.

Labour was able to neutralise negative mainstream media coverage by speaking directly to voters. It is notable that Labour felt no need to share supportive messages in the mainstream media with its followers. By curating large communities of interest online and using these to promote real-world events, Labour was able to bypass a mediated and predominately hostile press. And Corbyn’s supporters in activist groups such as Momentum and the hyper-partisan media were able to successfully amplify these messages.

Of course, Labour didn’t win the 2017 election. But its impressive social media campaign will unquestionably influence other parties’ strategies and tactics in future elections.

______

Matt Walsh is Head of Journalism at the University of Northampton.

Matt Walsh is Head of Journalism at the University of Northampton.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: The White House (CC BY 2.0).

I think I have noticed another side-effect of the 2017 election which resulted in a problem for the Conservatives. Before the election they always criticised Labour’s borrowing plans as dangerous because “there is no magic money tree”.

Yet when the Conservatives needed £1 billion to give to the DUP to get their support for a minority government the magic money tree was shaken and £20 notes fell from its branches. Even the great British public—whose knowledge of macro economics is thin—understood what was going on. (Incidentally the DUP will be back for more money in two years time.)

So that criticism of Labour borrowing had now become embarrassing; a new one was needed, something that economically-naive people can understand.

So the Conservatives settled on: “what about the interest that Labour would have to pay on their borrowing?” Although it’s a rather more complicated concept than a “magic money tree” a lot of people understand that you have to pay interest on a loan. The good news for the Conservatives is that those same people do not understand a country like the UK can borrow at incredibly low interest rates.

Great article especially as it was the younger voters who made all the difference at the last election. The pity is they were spun a few yarns to get them active!