Ron Johnston, Charles Pattie and David Rossiter consider the background to and likely electoral consequences of the delay in implementing agreed changes to Parliamentary constituency boundaries. The Conservatives had anticipated their chances of victory in 2015 would be enhanced by the reduction of the number of MPs and the introduction of new rules for defining equal-sized constituencies. Because of a ‘revolt’ by their coalition partners which prevented those changes being implemented they now face a much harder task of winning a majority in the current 650 constituencies

Ron Johnston, Charles Pattie and David Rossiter consider the background to and likely electoral consequences of the delay in implementing agreed changes to Parliamentary constituency boundaries. The Conservatives had anticipated their chances of victory in 2015 would be enhanced by the reduction of the number of MPs and the introduction of new rules for defining equal-sized constituencies. Because of a ‘revolt’ by their coalition partners which prevented those changes being implemented they now face a much harder task of winning a majority in the current 650 constituencies

A new feature for the British Politics and Policy blog is our ‘In Depth’ series. It provides an opportunity for us to host some longer posts by recognised leaders in their field tackling the analysis of important contemporary issues.

The chances of the Conservatives winning an overall majority at the next general election were significantly reduced on 29 January 2013 when they failed in the House of Commons to overturn a House of Lords amendment to their Electoral Registration and Administration Bill. This amendment delays implementation of the new procedures and timetable for the redistribution of Parliamentary constituency boundaries introduced in the long-debated Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act, 2011 until 2018.

Those new procedures were introduced by the Conservatives – supported by their Liberal Democrat coalition partners – who (rightly) believed they were disadvantaged by the current system for redrawing constituency boundaries every ten years. In 2010, for example, if the Conservatives and Labour had obtained an equal share of the votes cast – 32.55 per cent – Labour would probably have won 54 more seats in the House of Commons than its opponent. This was partly because the average Labour-won constituency had 69,145 electors, compared to 73,031 for those won by Conservatives. The latter got a seat for every 34,490 votes; Labour’s ratio was a seat for every 33,359 votes, and for the Liberal Democrats it was 119,933 – inequality in constituency electorates had an unequal impact.

To counter those differences, the 2011 Act required all constituencies, with four exceptions, to have electorates within +/-5 percentage points of the national average of 76,641. (The previous legislation only required electorates to be ‘as equal as practicable’ given other requirements – such as fitting constituency boundaries within those of local governments; Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales also had smaller constituencies on average than England.) Redistributions were to take place every five rather than ten years; the Conservatives were further disadvantaged as the electorates in their seats tended to increase over time, while Labour’s experienced relative if not absolute declines. The Boundary Commissions were to deliver their first reports using the new rules by October 2013, eighteen months before the scheduled next general election (under the Fixed Terms Parliament Act, 2011).

The 2011 Act also reduced the number of MPs from 650 to 600, on the grounds that this would save money (£12million annually) and improve public trust in politics by demonstrating that in an era of austerity politicians were accepting cuts too.

The Boundary Commissions started their reviews in March 2011 and published their initial recommendations some seven months later (there was a delay until early 2012 in Wales). Two features of those recommendations stood out. The first was that there was much greater disruption to the electoral map than at previous reviews, because of the combination of the equality requirement and reducing the number of MPs (the Welsh share was to fall from 40 to 30, for example, and London’s from 73 to 68). Many existing seats would be dismembered; many of the proposed new ones had little in common in terms of the areas served with those they were replacing. Many MPs thus faced the prospect of seeking selection for a very different seat from that currently represented, which caused much unease, even on the Conservative benches where many indicated general support for equal electorates and fewer MPs but were worried about their personal consequences.

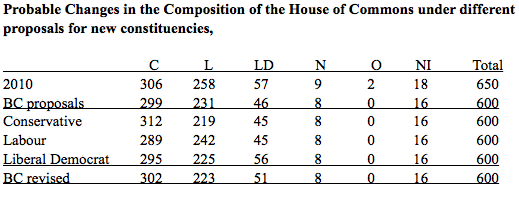

The second feature of the recommendations was that they substantially favoured the Conservatives. The first two rows of the table show that in 2010 the Conservatives won 48 more seats than Labour in a 650-seat House. If that election had been held in the Commissions’ proposed new 600 constituencies, with the parties having the same vote shares in the same places (wards), the Conservatives would probably have won 68 more seats than Labour; the Liberal Democrats’ share of the seats would have fallen from 8.8 to 7.7 per cent – further evidence the system works against them even more than the Conservatives! (These estimates were produced by Anthony Wells of YouGov and published on his website using the accepted methodology developed by British political scientists.)

No wonder that the Conservatives wanted the new rules to be implemented in time for the 2015 general election: their prospects of forming an (albeit small) majority government were much greater than if the existing constituencies were used again.

And there was more good news for the Conservatives. The Commissions’ provisional recommendations were subject to public consultation at which each political party could make counter-proposals, undoubtedly for alternative boundary configurations that would better serve its electoral interests. The government proposed that those consultations should involve written submissions only, but under House of Lords pressure reinstated a modified form of local inquiries (termed Public Hearings) alongside written submissions. These were held in late 2011-early 2012 and, like their predecessors, were dominated by the political parties, who mobilised local MPs, councillors, and party officials to speak and write in favour of their representations and counter-proposals.

The Commissions considered those oral and written submissions (although there were very few in either Northern Ireland or Scotland, almost none there from the general public) and produced revised recommendations in autumn 2012. None of the three main political parties got all that they asked for, which would have been impossible since in many cases they presented different counter-proposals for the same areas. But the two coalition partners got some of what they wanted.

The second block of three lines in the table indicates what the outcome could have been in 2010 if each party’s counter-proposals had been accepted in their entirety. Each would have gained more seats than in the Commissions’ initial recommendations, with their opponents suffering as a consequence. In relative terms, the Liberal Democrats would have been the main beneficiaries, increasing their number of MPs from 46 to 56: in absolute terms the Conservatives would have gained most, increasing their number from 299 to 312 (a clear majority). Labour, too, stood to gain 11 more seats if its counter-proposals were all adopted – despite not putting in any counter-proposals for either Scotland or Yorkshire and the Humber, as well as for only half of the Northeast region’s seats. The SNP submitted no counter-proposals: it currently holds six seats, and it was estimated to retain six in the Commission’s recommendations, despite the reduction in the number overall. Plaid Cymru’s counter-proposals could not change its likely complement of MPs from two. In Northern Ireland, only the DUP made counter-proposals.

The Liberal Democrats and Conservatives were most successful in getting some of their counter-proposals accepted in the Commissions’ revised recommendations, shown in the table’s final row. The former gained five more seats than under the initial recommendations (all of them in England) and the Conservatives a further three. Labour’s likely share was consequently reduced by eight seats from the initial recommendations, giving it 37.1 per cent of the 600 MPs compared to 39.7 per cent of the current 650 – with the same share and geography of the votes.

Those revised recommendations were subject to further public consultation – written representations only, with a closing date in late 2012. At previous redistributions this last stage rarely generated significant changes, which would probably have been the case again in three of the four countries. England may have had a few substantial changes if the Commission responded to the large number of written representations, however, because some of its revised recommendations differed substantially from the initial ones and raised local concerns. (Labour’s MP for Great Grimsby, Austin Mitchell, initiated a Westminster Hall debate because his constituency had been unexpectedly split into two; both of the new seats were likely to be Conservative gains.) But we may never know.

Labour opposed the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act, 2011’s changes to the redistribution procedures on several grounds and its MPs would almost certainly have voted against the Commissions’ final recommendations when they were laid before Parliament in late 2013, but the Conservatives expected the coalition to pass them. However, in August 2012 the Deputy Prime Minister announced that the Liberal Democrats would vote against them, because Conservative MPs had voted against the timetable motion for the House of Lords Reform Bill, 2012; that Bill was therefore withdrawn and his party lost the opportunity of a major constitutional reform it (like the other parties, in principle) was committed to.

This split in the coalition meant the Conservatives would find it very hard to create a majority to pass the Orders implementing the Commissions’ recommended constituencies. Although hoping that a deal could still be done with the Liberal Democrats and/or some of the minor parties (notably the DUP) to ensure their passage, therefore, the Conservatives began preparing for the 2015 general election campaign by identifying their target seats, and selecting candidates, among the existing constituencies. The other parties followed suit.

And then the possibility of the Orders even being laid before Parliament was removed. In autumn 2012 the House of Lords debated the government’s Electoral Registration and Administration Bill. It was long believed that only around 92 per cent of those eligible were registered on the electoral roll and the previous Labour government prepared legislation to change the registration method from a household to an individual basis, following a similar change in Northern Ireland a few years previously – hoping that this would result in a more complete and accurate roll. This was not implemented, but the coalition government introduced a Bill with the same intent, after the Electoral Commission reported research that only 85 per cent of those eligible were now on the roll. The change would not affect the 2011-3 boundaries redistribution – which was using the electoral roll compiled in late 2010 – but could have a very substantial impact on the post-2015 review.

During the Bill’s second reading debates in October 2012 a Labour peer, Lord Hart (a lawyer and former advisor to successive Lords Chancellor), tabled an amendment in which he was joined by a Liberal Democrat (Lord Rennard – an elections expert), a senior Plaid Cymru peer (Lord Wigley), and a cross-bencher (Lord Kerr – a retired diplomat). This would amend the Parliamentary Constituencies Act, 1986 (itself amended by the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act, 2011 to incorporate the new rules for redistributions and the reduced number of MPs) by delaying the date of the Boundary Commissions’ first reports until October 2018. The Clerks of the House advised the then leader – Lord Strathclyde – that the amendment should not be accepted for debate since its contents were not related to the Bill’s subject matter, but its sponsors disagreed (using legal advice from Labour election experts) and declined to withdraw it. Debate on the Bill was halted.

The debate recommenced in January 2013, with Lord Hart again declining to withdraw the amendment; when it was voted on peers were expressing their opinion (in the single division) not only on the amendment’s substance but also on whether the Clerks’ advice should be rejected (a very rare occurrence). The amendment was carried and became part of the Bill. When it was returned to the Commons the Conservative party moved that it be rejected, but the Liberal Democrats voted against and the motion was lost by 334:292: the amendment became part of the final Act. This ended the current Boundary Commissions’ review prematurely and ensured that the 2015 general election would be held in the existing constituencies.

Two main arguments favoured the amendment. The first was party political: the changed rules were part of the coalition agreement on constitutional reform, which also included the AV referendum and House of Lords reform. Liberal Democrats argued that they comprised a package and that by reneging on part (House of Lords reform) the Conservatives had failed to deliver on their agreement – and so the Liberal Democrats sought ‘revenge’.

The other argument, with which Labour speakers concurred, was substantive and concerned the electoral equality element of the new rules, with which both parties claimed they agreed – with a caveat. If fully implemented, the new electoral registration procedures should ensure that the review of Parliamentary boundaries commencing in 2016 is based on a (near-?) complete roll. But the constituencies to be proposed in 2013 were not and if electoral equality is to be the paramount determinant then they should be based on complete and accurate data. However, the roll compiled in 2010 is some 15 per cent incomplete. Certain social groups – the young, students, ethnic minorities, those who have recently moved, and residents of rented flats – are less likely to be registered than others. They are relatively concentrated in some parts of the country (notably inner cities), so if the electoral roll used for the review just stopped were complete London, for example, could have been allocated as many as 75 seats in the 600-member House of Commons, rather than 68. The main electoral beneficiary of those people being on the register would undoubtedly have been Labour, hence its support for the delay until after introduction of individual registration (though the likelihood of success in achieving a more complete roll is questioned by some, including the administrators responsible for its implementation).

So what is the current situation? Electorally

- The 2015 general election will be fought in the current 650 constituencies, defined using electoral data up to fifteen years old and with very substantial variations in electorates. (The latest data – for December 2011 – show three English constituencies with fewer than 60,000 voters whereas 49 have more than 80,000 and two more than 90,000.) Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland will continue to be over-represented. (The current average English constituency electorate is 72,658: it is 57,464 for Wales, 67,372 for Northern Ireland, and 66,807 for Scotland.)

- The Conservatives will find it much harder to win an outright majority in 2015. The most likely outcome, given the present state of the polls, is a Labour victory (its extent depending on the degree to which 2010 Liberal Democrat supporters switch to Labour and Conservatives transfer their allegiance to UKIP: UK Polling Report is currently suggesting a Labour majority of 92!). But another coalition is also quite possible.

- There is a further potential complication. If Scotland votes for independence in 2014, the date for separation is currently set for March 2016, so will it elect 59 new MPs in 2015 to influence UK policy for a year? The composition of the next government may depend on whether it does – and, if so, whether those MPs participate. Labour may only have a majority in the House of Commons between May2015 and March 2016!

What of the longer term? The Boundary Commissions will begin their next review in early 2016, using what it is hoped will be a much more complete electoral roll than the current one. With no change to either the rules or the reduction to 600 constituencies that review will be at least as disruptive as the one just prematurely ended, probably more so because by 2016 there will be greater electoral inequality across the current constituencies than in 2010: the allocation of seats across the UK’s four countries may even change. The map of new constituencies presented in 2018 may be very different from that which existed in embryo in early 2013.

If the Conservatives either form the next government or are the largest party in a coalition, they will probably allow that review to go ahead, perhaps slightly amended (although to do so will mean early post-election legislation). Although most current Conservative MPs accepted the paramount emphasis on electoral equality not all were convinced that the range should be as tight as +/-5 per cent: many might have preferred a range of 7-10 per cent as likely to be much less disruptive. Many, too, seemed unconvinced of the case for reducing the number of MPs: amendments that kept the House of Commons at 650; they may well be even more unconvinced now, but keeping the equality paramount requirement (perhaps slightly relaxed) might be more acceptable.

If Labour wins in 2015, or is the largest party in a coalition, it will probably want to change some of the 2011 Act’s provisions along similar lines. But it may want further modifications – to the public consultation procedure, for example – and by the time legislation is passed the Commissions’ reviews may not be completed and new constituencies will not be in place in time for the 2020 general election. If so, that contest will be fought in constituencies defined using data two decades old: even excluding the extreme cases in the Hebrides, Orkney, Shetland and the Isle of Wight, there may be constituencies whose electorates are four or more times larger than those of the smallest.

Was the procedure used in the review just prematurely ended satisfactory? Were the new rules readily applied? Was the public consultation procedure hastily cobbled together in January 2011 fit-for-purpose (the government spokesman in the Lords claimed the procedure used between 1958 and 2007 was not)? There is no commitment to a review until after the Commissions have delivered their first reports – which will now be in 2018. Perhaps one should be convened (by academics in consultation with the Commissions and the political parties?): we were close enough to the end of the current exercise for important lessons to be learned and fed in to any post-2015 legislative amendments. Or the Fixed Terms Parliament Act, 2011, could be repealed.

The main impact of the House of Commons’ decision on 29 January to delay the next redistribution of Parliamentary constituency boundaries, therefore, is that the Conservatives will find it even harder to win an outright majority in 2015 than they hoped might be the case. The nature of the next government may well be determined by the Liberal Democrats’ act of ‘revenge’ for their coalition partner’s MPs being unwilling to support lengthy debates on House of Lords reform. And if the Conservatives don’t win in 2015, this will undoubtedly determine David Cameron’s bleak future as their leader.

Ron Johnston (of the University of Bristol), Charles Pattie and David Rossiter (University of Sheffield) co-authored the standard reference work on ‘The Boundary Commissions’ (Manchester University Press, 1999) and have published several academic papers on the 2011 Act and its subsequent implementation.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography in the School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Bristol. His academic work has focused on political geography (especially electoral studies), urban geography, and the history of human geography.

Charles Pattie is Professor of Geography at the University of Sheffield. His main research area is in electoral geography and political participation

David Rossiter has worked in a research capacity at the Universities of Sheffield, Oxford, Bristol, Leeds and Essex. He has been involved in the redistricting process both as academic observer (for example The Boundary Commissions, MUP, 1999) and as advisor to the Liberal Democrats at the time of the Fourth Periodic Review.