It is currently likely that no party will be a clear winner in next May’s General Election. What is much less clear is how many MPs each party will have and who will lead the next government. In this post, Ron Johnston, Charles Pattie and David Rossiter explore why the composition of the House of Commons after next May’s election is difficult to predict.

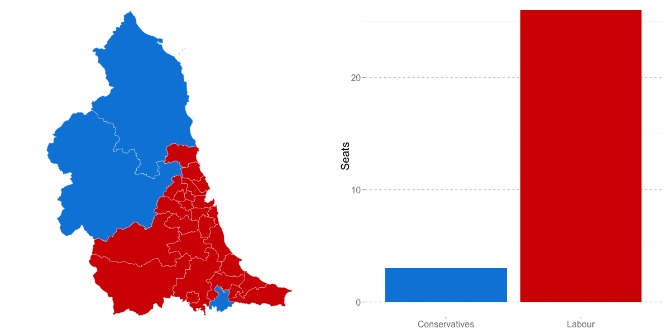

Polling vote share estimates have considerable credibility but translating them into seat numbers is fraught with difficulty. In 2005 Labour got 35.2% of the votes and 55.1% of the seats. Five years later, with 36.1% of the votes the Conservatives got fewer seats (47.2%). And, of course, in 2010 the Liberal Democrats’ 23.6% of the votes delivered only 8.8% of the seats.

The polls currently suggest a only small Labour-Conservative vote share gap; they might even tie. Had they tied in 2010, Labour would have had a 50-seat lead over the Conservatives. Why, and might it happen again in 2015?

Labour’s advantage came about because, on average, it needed fewer votes to be successful in the seats it won than did the Conservatives. This was partly through variations in constituency electorates. Welsh seats, for example, had on average some 16,000 fewer voters than English ones. Labour is the stronger of the two parties there and got a better ratio of votes to seats than its opponent. This, plus a much smaller difference between English and Scottish seats, was worth some 8 seats to Labour – and could be again in 2015 (assuming Scottish Labour does not collapse).

Variations in constituency electorates within England, Scotland and Wales all favoured Labour, largely because over time some seats (which tend to be Conservative-won) grow faster than others and some, almost all Labour-held, decline. This gave Labour a ten-seat advantage in 2010; after five more years of population change, it could be larger in 2015.

Turnout has been around 60 per cent at recent elections and growing discontent with politics, the parties and their leaders means it is unlikely to increase. It also varies across constituencies; where it is lower, fewer votes are needed on average for victory. Labour tends to be strongest in low turnout areas. In 2010 if Labour and the Conservatives had received the same share of the vote, Labour would have won 30 more seats because of this alone. It should glean a similar advantage in 2015.

A very close 2015 result between the two leading parties in vote shares could therefore give Labour a clear lead over the Conservatives in terms of seats (even if Labour came second) because of variations in constituency electorates and in turnout. But between them they are unlikely to get more than two-thirds of the votes. The Liberal Democrats, UKIP, the Greens, Plaid Cymru and the SNP will all win votes – and seats. How will this affect the Labour-Conservative balance? (As Labour and the Conservatives don’t contest seats in Northern Ireland, the results there have no impact on the overall seats to votes ratio.)

When the Liberal Democrats won lots of votes but few seats they were most successful in Conservative southern heartlands, reducing the number of votes needed to win seats there – to the Conservatives’ advantage. But when they won more seats – mainly from the Tories – Labour benefited. And then they started to win votes and seats in northern cities, reducing Labour’s benefit. In 2015 they are likely to lose more northern than southern votes, benefiting the Conservatives – unless many LibDem incumbents retain their seats.

UKIP could have the same effect. Its impact is likely to be greatest where the Conservatives are strongest – reducing the number of votes the Tories need to win seats (benefiting David Cameron!). But if UKIP win more than a handful of seats, Labour could be the net beneficiary. And then there is the SNP, currently leading Labour in Scottish polls. This could be a substantial advantage to Labour, however, because very few Labour-held seats have a majority over the SNP of less than 10 per cent. If the SNP win lots of votes but few seats, Labour gains, but if the SNP can win a lot of seats (20 or more), Labour’s advantage could wither.

So it is a cliffhanger. Labour has a potential advantage of up to 50 seats over the Conservatives if few votes separate them on 7 May. Good UKIP and Liberal Democrat performances in the contest for votes but not seats could erode that advantage. But perhaps the SNP holds the key to Number 10: more votes but not seats for them and Miliband could be Prime Minister; more seats as well as votes, and all sorts of coalition configurations might come into play.

About the Authors

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography at the University of Bristol. Ron’s academic work has focused on political geography (especially electoral studies), urban geography, and the history of human geography.

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography at the University of Bristol. Ron’s academic work has focused on political geography (especially electoral studies), urban geography, and the history of human geography.

Charles Pattie is Professor of Geography at the University of Sheffield, specialising in electoral geography.

David Rossiter has worked in a research capacity at the Universities of Sheffield, Oxford, Bristol, Leeds and Essex. He has been involved in the redistricting process both as academic observer (for example The Boundary Commissions, MUP, 1999) and as advisor to the Liberal Democrats at the time of the Fourth Periodic Review.

(Featured image credit: John Keane CC BY 2.0)

1 Comments