In this article, Geoffrey Evans and Jonathan Mellon examine the voting history of UKIP supporters, finding that the party is attracting, primarily, disaffected former Labour voters from the Conservatives and elsewhere, and that the working class basis of UKIP has been markedly over-stated. On the whole, however, it is the Conservatives, not Labour, who have most to fear from UKIP.

In this article, Geoffrey Evans and Jonathan Mellon examine the voting history of UKIP supporters, finding that the party is attracting, primarily, disaffected former Labour voters from the Conservatives and elsewhere, and that the working class basis of UKIP has been markedly over-stated. On the whole, however, it is the Conservatives, not Labour, who have most to fear from UKIP.

The idea that many UKIP voters are working class and that UKIP therefore pose a threat to Labour’s support in the forthcoming election has gained considerable currency in recent years. But how do we reconcile evidence of UKIP support among traditional working class voters, and in Labour constituencies, with evidence that UKIP voters report voting Conservative in 2010?

We resolve this contradiction using individual-level panel data stretching back to 2005 to examine the sequencing of vote switching from Labour to UKIP. We go on to demonstrate how support for UKIP is even higher among the self-employed and business owners than the working class, and that is quite high even in the professional & managerial classes, who because are their substantial numbers actually provide the biggest bloc of UKIP’s class-based support. For all of these reasons the Conservatives, not Labour, have most to fear from UKIP.

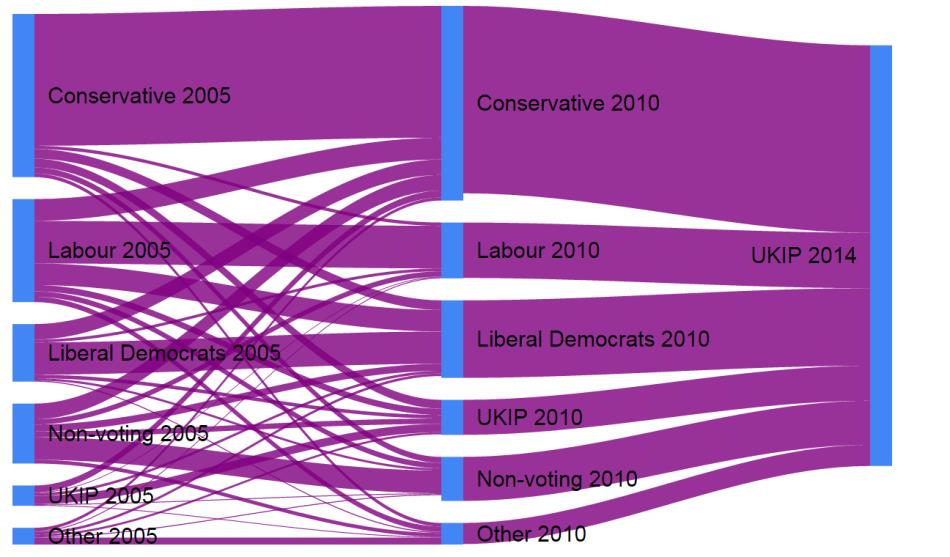

The figure below presents the flow of the vote to UKIP from 2005–2014 using respondents who were in the 2005 and 2010 BES panel surveys as well as those in the third wave (autumn 2014) of the current 2015 BES panel study.

We can see that UKIP’s voters are overwhelmingly taken from those who voted Conservative in 2010. Even the Liberals lose more to UKIP than do Labour. However, we can also see that 2005 Labour voters also gravitated to UKIP. What distinguishes them is that they did so via more circuitous routes. The clear majority of 2005 Labour voters who supported UKIP in 2014 had left the party by 2010: 80 per cent of 2005 Conservatives who intended to vote for UKIP in 2014 were still Conservative in 2010, whereas a mere 40 per cent of 2005 Labour voters were still Labour then. So Labour’s loss to UKIP is partly hidden by its supporters having gone through other paths prior to arriving at UKIP.

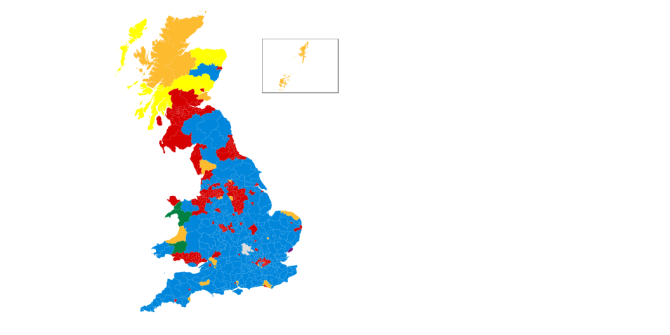

This is confirmed at the constituency level. If we look at UKIP supporters in Labour seats we see that only 20 per cent voted Labour in 2010, whereas 44 per cent were Conservatives, whereas in 2005 35 per cent of these voters supported Labour and only 38 per cent were Conservative. The answer to why UKIP are doing well in Labour seats but are unlikely to win these seats is that there are still a lot of Conservative voters in Labour seats (25 per cent of the vote in 2010 on average) and many of these are 2010 Labour defectors. UKIP have picked up support disproportionately from former Labour voters in Labour constituencies.

These defecting Labour voters are to a large degree the sorts of people that New Labour will have alienated following its centrist shift during the Blair years.[1] The move to the ‘liberal consensus’ on the EU and immigration led to many of Labour’s core voters losing faith in the party before UKIP were an effective political presence.

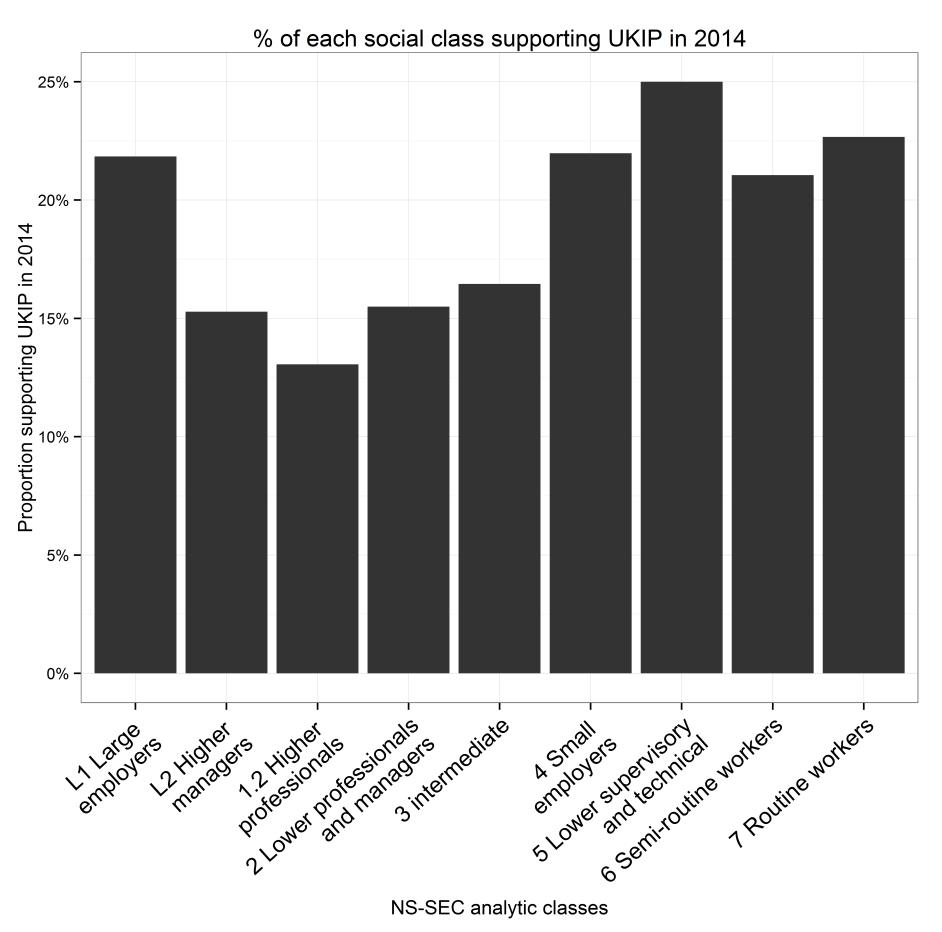

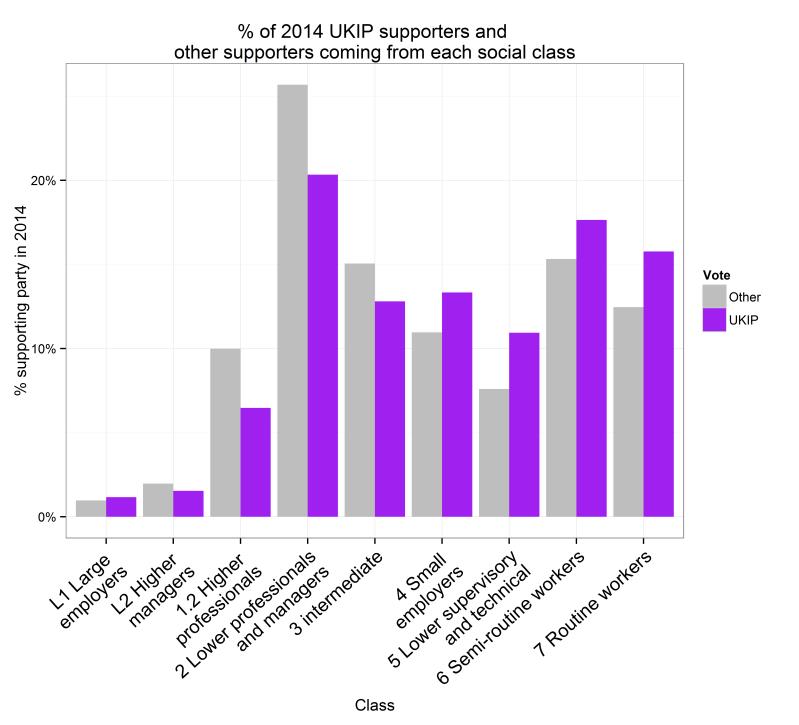

However, there is a further point also not previously noted. Not only is UKIP attracting, primarily, disaffected former Labour voters from the Conservatives and elsewhere, but the working class basis of UKIP has been markedly over-stated. Working class voters are a little more likely to support UKIP than other classes, but there is stronger support among the self-employed and business owners, who were Mrs Thatcher’s hard-core supporters, not Labour’s.[2] Even within the working class, the strongest UKIPers are the lower supervisory category, who are not the disadvantaged semi- and unskilled workers that have been thought to provide the core of UKIP support.

So UKIP’s support is very similar in social composition to support for many other, so called, ‘radical right’ parties elsewhere in Europe – an alliance between the working class and the self-employed (and employers) – rather than a party of the ‘left behind’. Even more significant, in electoral terms, the differences in sizes between the social classes means that numerically the bulk of UKIP’s support comes, counter-intuitively, from the larger professional & managerial middle classes. Thus providing even further reasons for the Conservatives to worry and Labour to remain calm in the face of UKIP’s emergence.

In a reply to our article, Rob Ford and Matt Goodwin argue that UKIP’s support may still become an electoral threat for Labour, particularly in Northern seats, and that since 2010 it has taken votes that would otherwise have gone to Labour. In our reply to Ford and Goodwin, we present evidence refuting these claims by using questions about ‘propensity to vote’ to examine voters’ second choices (i.e. who would they ever consider voting for?), to examine which party’s supporters are likely to be fertile ground for UKIP. We find that: (i) 45 per cent of current Conservative supporters have UKIP as a second preference, compared with only 19 per cent of Labour supporters; (ii) the potential for UKIP is slightly lower in Northern seats compared to those in the rest of England; and (iii) in the absence of UKIP, far fewer of UKIP’s current supporters are likely to have voted Labour (20 per cent), than Conservative (42 per cent). Labour has benefited from UKIP’s presence and is likely to continue to do so. UKIP is Labour’s secret weapon.

The research illustrated in this blog is presented in greater detail in these open-access articles: Evans, G & Mellon, J. 2015. ‘Working class votes and Conservative losses: solving the UKIP puzzle’, Parliamentary Affairs; Mellon, J. & Evans, G. 2015. ‘Class, Electoral Geography and the Future of UKIP: Labour’s Secret Weapon?’, Parliamentary Affairs.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the General Election blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Geoffrey Evans is an Official Fellow in Politics at Nuffield College, Oxford and co-director of the British Election Study 2015.

Geoffrey Evans is an Official Fellow in Politics at Nuffield College, Oxford and co-director of the British Election Study 2015.

Jon Mellon is a post-doctoral Research Fellow at Nuffield College, Oxford.

Jon Mellon is a post-doctoral Research Fellow at Nuffield College, Oxford.

[1] Multivariate models of vote find predictable patterns: the working class, employers and anti-EU 2005 Labour voters tend to be those who ended up supporting UKIP. That the EU and immigration eventually merged as an issue, particularly after the 2004 accession of former Communist countries, is also indicated by the similarity in the patterns of attitudes towards immigration and Europe shared by those who did or did not switch from Labour to UKIP.

[2] We find for example that 62 per cent of UKIP supporters think that Thatcher was good for Britain, compared to 44 per cent in the population as a whole.

Very interesting data and analysis. I suspected all along that the Ukip threat to Labour had been exaggerated, because in northern urban seats where Ukip did well the Labour share seemed to have gone up too – but not as much, so the outcome could be read as a ‘swing’ from Ukip to Labour, a misleading statistical artefact. Somebody has to come second; that doesn’t make them a threat to whoever comes first. But some people also seemed to be overlooking the perennial working class Conservative vote, which has always been there (since 1867!) and not just a phenomenon of Thatcherism. The Tories collapsed in the big northern cities in the 80s and now the LibDems have followed them into relative oblivion. That anti-Labour vote has to go somewhere.