Polling Matters is an independent, non-partisan podcast providing expert polling news and analysis, with guests, in the run up to the General Election. In the most recent episode, Keiran spoke to PR and communications expert Mark Pack to get his take on the Liberal Democrats, how they might do at the General Election and what’s next for Nick Clegg and the Party after May.

Polling Matters is an independent, non-partisan podcast providing expert polling news and analysis, with guests, in the run up to the General Election. In the most recent episode, Keiran spoke to PR and communications expert Mark Pack to get his take on the Liberal Democrats, how they might do at the General Election and what’s next for Nick Clegg and the Party after May.

You can listen to this week’s polling matters podcast here.

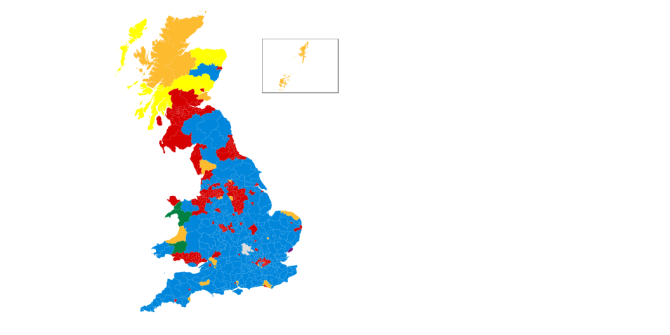

With all of the understandable attention paid to the rise of UKIP in England or the SNP in Scotland, it is still surprising how little attention has been paid to the collapse of the Liberal Democrats this parliament. Having achieved 23% of the vote in 2010, the party’s national vote share has languished in the single digits for some time with no obvious sign of improvement. In fact, if you plug last Sunday’s YouGov poll into electoral calculus they end up with just 10 seats.

Of course, the consensus among election forecasters is that the Lib Dems will do much better than this. Current projections tend to have them on around 25 seats after the election and maybe more. The reason is simple enough, they tend to poll much better in areas where they currently have an established presence, so their national vote share may collapse but they could still hold on to enough seats to remain relevant. The Lib Dems will hope the upcoming election will be a national version of the Eastleigh by-election where they held on to the seat despite a sharp drop in vote share. Indeed, Lord Ashcroft polling does provide some evidence for this ‘incumbency bonus’ that is so crucial to the Party’s prospects this election cycle.

Perhaps we shouldn’t exaggerate the point though. Even if the Lib Dems ended up with 27 seats (the top end of current projections) this still more than halves their number of seats in parliament. Furthermore, there is a very good chance that the SNP will become the third biggest Party in Westminster, with serious implications regarding short money for the Lib Dems. When we consider that both Nick Clegg and Danny Alexander could also lose their seats (we should be sceptical about polling saying otherwise we cannot see) the General Election promises to be a really tough one for the Party.

And yet, with neither the Conservatives nor Labour looking on course for a majority, they could still hold the balance of power once more.

Perhaps the most interesting question then is what do the Lib Dems do in such a situation? A ‘renewal of coalition vows’ was for a long time my expected outcome. It remains possible but seems increasingly unlikely. If the parliamentary Party loses half its seats, one could ask what the benefit would be for the Lib Dems to sign up to more cuts and an in/out referendum on EU membership. At the very least you can see why they would be cautious.

Is a coalition with Labour more likely then? Perhaps. I would argue it gives the Lib Dems a real chance of showing that they are an independent, grown up Party prepared to do deals with either of the major Parties seeking to form a Government. It is much harder for them to form their own identity whilst continually propping up the same governing Party. There is a third option though of course, perhaps most likely of all, to sit it out and rebuild from the back benches, maybe providing votes on a ‘confidence and supply’ basis’ to a minority government.

Of course, as Mark Pack rightly points out on the podcast, we should avoid over-emphasising how much choice the Lib Dems may have in the matter. Perhaps Miliband or Cameron will prefer to govern alone. Even if not, it is likely that the Lib Dems will realistically only have one Party to do a deal with and their negotiating position in that situation will depend on the parliamentary numbers. Even if our constitution allows the second biggest Party to form a Government it is difficult to imagine this happening.

So if anything is clear in these unclear times, it is that the Lib Dems face a very difficult election where polling day is just the start. The decisions they make from May 8th onwards will have significant implications for the Party’s long term future and very survival as a electoral force. We know that the number of people voting Lib Dem will drop sharply in May, how they come back from that is the biggest question of all.

Keiran Pedley is an Associate Director at GfK NOP and presenter of the podcast ‘Polling Matters’. He tweets about politics and polling at @keiranpedley.

Keiran Pedley is an Associate Director at GfK NOP and presenter of the podcast ‘Polling Matters’. He tweets about politics and polling at @keiranpedley.

Hi Both.

I am not saying it would be unjust or wrong, just hard to imagine which I stand by. I think politically it would be very very difficult for the second biggest party to lead a Government, particularly in the example Christian raises (not many Lib Dems / DUP / UKIP in there btw) .

Perhaps in some highly specific scenario where the result is extremely close and the biggest party (probably the Conservatives in that situation) cannot get it done then maybe. But I think its hard to see which is my point. On balance, I think it is fair to say the largest party is most likely to form Government.

But my main point is not to debate the merits / likelihood of this but rather to raise Mark’s point on the podcast about the Lib Dems and the lack of real choices they may actually have in a hung parliament. If they do not have many seats and one of the major parties leads on seats then its difficult to see how much bargaining power they really have, whatever the constitutional realities. I may be wrong, we will see.

Thanks for reading

Keiran Pedley: “Even if our constitution allows the second biggest Party to form a Government it is difficult to imagine this happening.”

Seriously? Why is that? You don’t say. What’s the rationale? Do spare us the Labour trope that the biggest party forms the government. That is usually the case ONLY because almost always a party wins a majority of seats at the election.

Now it should not be difficult for any higher primate to work out that in that case OF COURSE the largest party forms the government – not per se because it is just the largest party, but because IT IS THE MAJORITY PARTY.

The case at issue here is the exception, where no party has a majority – i.e., one of the few instances where we have a hung parliament.

So, lets look at an actual real-life example, shall we? 1923 election result gave us a hung parliament :

Con 258

Lab 191

Lib 158

Who formed the government? Why, LABOUR FORMED THE GOVERNMENT.

They had FAR fewer seats than the Tories, but they still formed a minority government BECAUSE THEY COULD COMMAND THE CONFIDENCE OF THE HOUSE. That is to say, what matters is not who comes first or second in a hung parliament, but who can put together a majority to win a vote of confidence. Coming first or second in a hung parliament is of no consequence – it’s all about commanding a majority.

If you command a majority in the House you can form a government – period. It matters not one bit whether you are the largest party or whether the parties comprising the majority also comprise a majority of the popular vote. That has no relevance in our system.

Let’s bring it up to date. Consider the following: Example results May 7, 2015 election

Con 300

Lab 280

SNP 46

Oth 24

Lab + SNP = 326 = A MAJORITY OVER ALL OTHER PARTIES IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS (Sinn Fein and Speaker’s seats NOT excluded)

The SNP holds the balance of power. Since the SNP will ONLY prop-up a Labour government, there can ONLY be a Labour minority government OR a Lab/SNP coalition government, even though Labour are the SECOND largest party and even though Cameron in the incumbent PM.

Summarising:

1. The Party that commands a majority in the House will form the next government and that is not necessarily the largest party.

2. Even minority governments must command a majority in votes of confidence and supply.

3. It doesn’t matter who gets first dibs at forming a government. ALL that matters is which party or group of parties can command a majority in the House and win the confidence vote.

4. It does not matter who may command the popular vote, nor who may be the incumbent PM

It is false to assert that the largest party will, or will almost certainly, form the next government (as many members of the commentariat do) or that it is “difficult to imagine” the party coming second in a hung parliament would form a government. It is in no way difficult to imagine.

The largest party MAY form the next government, then again, it may not. Whether a party is the largest party in a hung parliament or not offers ZERO operational advantage.

Some projections, including mine, indicate that the Lib Dems may get a few more seats than that – perhaps over 30. But I don’t see why “Even if our constitution allows the second biggest Party to form a Government it is difficult to imagine this happening.” The main thing necessary to form a government is to command the confidence of the House of Commons. The second party has formed a government before, and undoubtedly will again at some point in the future, unless someone actually writes a UK constitution and includes a clause that forbids it!