Most newspapers concluded that the Tories mainly won over Lib Dem and Labour waverers to score a surprising majority in the general election. However, as Eric Kaufmann shows here, it was really the English nationalist penumbra around UKIP, rather than Lib Dem or Labour switchers, that explains the great polling calamity.

Most newspapers concluded that the Tories mainly won over Lib Dem and Labour waverers to score a surprising majority in the general election. However, as Eric Kaufmann shows here, it was really the English nationalist penumbra around UKIP, rather than Lib Dem or Labour switchers, that explains the great polling calamity.

Like most who watched the election, I was stunned by the exit polls released at ten o’clock in the evening after polls closed. Former Lib Dem leader Paddy Ashdown told the BBC’s Andrew Neil that he would eat his hat if the picture they painted – of Tory victory and Lib Dem collapse – proved correct.

We now know it was, but the reason remains a mystery. Are there any clues? Yes, and the smoking gun points at UKIP. Or rather the ‘shy’ English nationalists whose pulse is reflected in local UKIP voting, but whose numbers extend well beyond it. As academic surveys such as the British Election Study (BES) and Understanding Society (UKHLS) reveal, both UKIP supporters and non-voters are overrepresented among those who refuse to answer questions about income or class on surveys, are dissatisfied with their neighbours and their lives, and are less trusting of others. It shouldn’t surprise us that these people are less likely to answer a poll.

In short, there is a silent minority of English nationalists whom UKIP draws upon. The Tories managed to scare enough of them away from non-voting and UKIP to win while convincing a small but important group of voters from other parties.

This isn’t the story that made the papers, however. Most focused on the Lib Dem collapse and Labour’s poor showing, concluding the Tories mainly won over Lib Dem and Labour waverers. UKIP’s share, at almost 13 per cent, was close to that predicted by the polls, so the pollsters patted themselves on the back that they got that one right. The press suggested UKIP’s 120 second place finishes, over a third in Labour seats, indicated they hurt Labour more than the Tories. However, this flies in the face of large datasets such as the BES, UKHLS and Ashcroft constituency polls. As Geoff Evans and Jon Mellon, as well as myself, have argued, UKIP disproportionately hurts the Tories, not Labour, by grabbing part of the Tories’ English nationalist voting base.

How do I conclude that the English nationalist penumbra around UKIP, rather than Lib Dem or Labour switchers, explains the great polling calamity? Ashcroft constituency polls formed the bedrock of most election forecasts, so I compared them with actual results in 130 marginal seats to see where he went wrong and where he called things right. It turns out the Tory’s surprising performance diverged most from predictions in seats where UKIP was slated to succeed. The exceptions were six high profile UKIP targets where the polls were pretty accurate: Boston, Thanet South, Thurrock, Rother Valley, Dudley North and Great Grimsby.

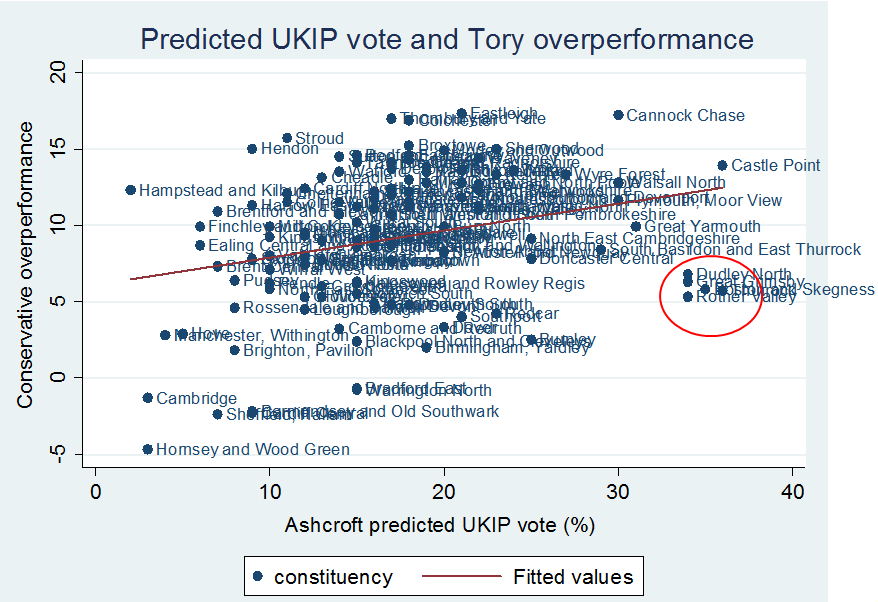

Take a look at figure 1. The vertical axis represents the ‘surprise’ factor: the proportion by which the Tories exceeded Ashcroft’s expectations. The horizontal axis shows UKIP’s predicted vote share in Ashcroft constituency polls, a good measure of the strength of UKIP in a given constituency. Notice how, with the exception of the UKIP targets in the circle, the Tories were more likely to surprise the pollsters in UKIP-friendly seats. The dots cluster more tightly when we look at Tory overperformance as a percentage of predicted vote, but in both cases the results show a significant relationship. The share of the population without qualifications, or who identify as English not British, also predicts where the Tories exceeded expectations, but not nearly as sharply as predicted UKIP vote does.

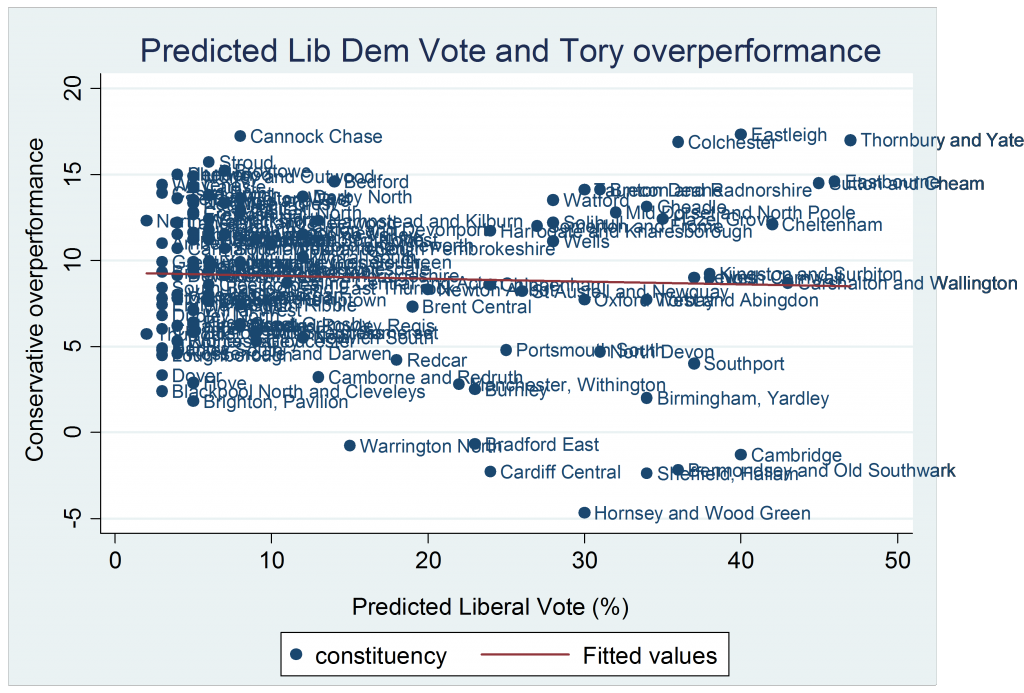

This can’t be said for the association between Tory overperformance and the predicted Lib Dem, Conservative or Labour share: predictions were not systematically off-target in strong Lib Dem or Labour marginals. This casts doubt on the view that the Tories did best among Lib Dem or Labour floaters. The Lib Dem equivalent appears in figure 2. Notice the flat line and looseness of fit of points around the line. The story of election night was not that Lib Dems flocked to the Tories. If that were true we would see the biggest Tory surprise gains in the seats where the Lib Dems were predicted to be strongest. The same point holds for Labour.

It’s instructive to look at the two seats where UKIP won byelections in 2014: Clacton and Rochester & Strood. In Clacton, Douglas Carswell hung on to his seat with 44 per cent of the poll, but lost nearly 1,500 votes – and 15 points of vote share – compared to the 2014 by-election. All of his challengers increased their share against him: Labour by 61 per cent, the Lib Dems by 68 per cent and the Tories by 86 per cent. The same thing happened in Rochester. Conservative candidate Kelly Tolhurst increased her vote by almost 60 per cent to 23,000 while UKIP’s Mark Reckless lost almost 1,000 votes against his 2014 tally to come second, with 16,000. At the same time Labour increased its vote in Rochester by 55 per cent and the Lib Dems by a whopping 258 per cent. Turnout went up by around 8,000 between 2014 and 2015 in both seats, so we should have expected UKIP’s numbers to rise. Yet they alone lost votes. These are seats where the Tories gained at UKIP’s expense while leaving others more or less unscathed. This is because ‘hidden’ English nationalist nonvoters came out for the Tories while some English nationalist UKIP voters switched to Cameron – all in response to the SNP-Labour threat. In a different election such folk may have swelled the ranks of UKIP, floating Carswell to victory.

It’s often forgotten UKIP won the European election, with 27.5 per cent of ballots. The BES internet panel’s fourth wave, conducted in March 2015, showed that 56 percent of those who voted UKIP in the 2014 election intended to vote for Farage in the general election. This should have put UKIP on around 15-16 per cent, 3-4 points above where polls placed the party. On its own, a switch of 3-4 points from UKIP to the Tories is not enough to have swayed the election, but what if this was just the tip of the iceberg?

The phenomenon of the ‘shy’ Tory is much commented upon, but pundits have failed to notice the ranks of hidden English nationalists from whence they spring. The more uprooted and radical of this stripe turned to UKIP, but the more traditional among them may be inclined to stick with the habits of their family or locale. UKIP voters tend to live in rural, less educated communities which pollsters find harder to reach. If there is a hidden mass of English nationalist voters who waver between the Tories, UKIP and staying home, Nicola and Ed spooked them in Dave’s direction. This explains why the Tories surged most in UKIP-friendly areas except high-profile battlegrounds such as Thanet South or Rochester where the mobilisation of English nationalists had reached saturation point.

If the swiftly-announced independent enquiry into the polling industry wants to find some answers, it should forget about Lib Dem and Labour switchers and hurry over to UKIP country.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: Jonathan Rolande CC BY 2.0

Eric Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck College, University of London. His latest publication is a Demos report, freely available, entitled Changing Places: the White British response to ethnic change.

Eric Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck College, University of London. His latest publication is a Demos report, freely available, entitled Changing Places: the White British response to ethnic change.

Yet again Occam’s Razor is overlooked in a bizarrely overcomplicated attempt to explain the obvious.

– What do UKIP voters want above anything else? An EU referendum.

– Of the two people who could possibly have been Prime Minister, how many were offering an EU referendum?

Contrary to what self-styled intellectuals, particularly on the left, would like to believe, UKIP voters aren’t morons (at least, proportionately no more so than supporters of other parties). They understand how FPTP works just like everyone else does.

They knew that in seats where splitting the right-wing vote risked letting Labour in, it might lead to Ed Miliband becoming PM and denying them the one prize they really wanted. So they stuck with UKIP in the north where it couldn’t hurt the Tories, and elsewhere they held their nose and made sure a man who’d promised an EU referendum got into Downing Street.

It had nothing to do with the SNP – they didn’t want Labour in power whether the SNP were involved or not.

John – The tactical vote scenario you lay out is interesting and no doubt contributed, with UKIPpers defecting Tory. But the numbers are not sufficient to account for the pattern of Tory success in seats with a strong UKIP presence. In another blog (at New Statesman May2015 linked in the article), I show how even a 50% UKIP collapse would only have led to 6-8 seats going Tory, and we know UKIP got 13%, which is respectable. Rather, I take the UKIP predicted share as indicative of a density of ‘shy English nationalists’ in a constituency who refuse or elude pollsters but came out of the woodwork because of the SNP threat. I was speaking to Bobby Duffy at Ipsos-Mori and they noted that the numbers may have been caused by young Labour/Lib voters not turning out. But then we should have seen Tory overperformance highest in Labour, Lib or young marginal seats and that was not the case.

Interesting. But ignores the tactical voter. I would have liked a labour victory and voted for them. But if I lived in a Tory / UKIP marginal I would have voted through gritted teeth for conservative to keep Farm getting, Reckless or Carswell out. I am not a shy English Nationalist, but recognise with our election system you sometimes have to accept the lesser of two evils.

Some interesting comments here. Robert, this is a blog post not an academic article so I mention the results are significant but don’t present stats. But here they are: R2=.237 if 6 marginals excluded, .140 if included. 1 pt rise in predicted UKIP share=.41 of a point rise in conservative overpeformance. .406(.072)***. For Lib Dems, R2=.018, -.026(.031).

Simon, in both BES and Understanding Society, English national identity one of strongest predictors of UKIP voting. Though rhetoric is Unionist, appeal, I believe, is more tied to English nationalism

Howell – I find a consistent association between Ashcroft’s errors and predicted UKIP support, but no link with Lib Dem or other party support. Ashcroft’s errors are moot – there is a significant relationship which demands an explanation: I see predicted UKIP vote as an indicator of a seat’s level of latent English nationalism and these are the ones where Tories surprised the pollsters

I’d argue that UKIP very much does harm the Labour vote. While it’s true there is some ex-Tory UKIP, the vast majority come from the poor working-class; victims of the Thatcher regime and subsequently abandoned by Labour in it’s lurch Right during the nineties. Feeling legitimate anger and despair at their decades-long worsening economic position and lack of representation, their frustrations have been re-directed by government and media scapegoating about immigration.

If Labour wants to regain lost ground before 2020 and break the decades long two-party deadlock, it is this demographic it needs to engage with and genuinely listen to.

Isn’t there a basic problem here, that your two data sets are just (a) the Ashcroft polls, with all of there demonstrable predictive errors baked in, and (b) the actual results? So is what you are measuring real behaviour, or just the errors in Ashcroft’s methodology?

This is a very interesting article, but why are people who voted for the Conservative Party (the use of ‘Tories’ makes little sense given the mainstream Conservative abandonment of Tory principles) to be categorised as (‘shy’) ‘English nationalists’? What evidence is there that voting behaviour last Thursday can be accounted for by overt or covert English nationalist sentiment? UKIP, like the Conservative Party is after all a constitutional Unionist and British nationalist political party. If you are either a Scottish or English nationalist, and place the identity and interests of your nation ahead of all others, by definition you cannot also be a supporter of the British Union and the United Kingdom.

In terms of the ‘English, not British’ category, it is worth reflecting upon the results of the 2011 Census, and the 32.4 million respondents who chose to define their identity in such terms. Are they too now to be regarded as ‘English nationalists’?

Without, at the very least, a measure of correlation and statistical significance, that graph is a load of codswallop. Don’t they teach statistics at the LSE these days?

He’s from Birkbeck not LSE, but yes it’s a bit tenuous in my opinion.

Botzarelli, you make a good point. My argument is that in the 6 high profile UKIP targets like Clacton & Rochester – which I circled – nationalists were not shy but had been mobilised by the media and local campaigners. And there the polls called it pretty accurately: notice that the Lib Dem vote increased a lot in both Clacton and Rochester over 2014-15, in line with other parties.

Where the Tories defied the polls is in UKIP-friendly seats among the other 124 marginals. This is partly due to UKIP-Tory defection, but mainly, I think, due to shy English nationalists who sympathise with UKIP aims but are probably Tory by custom. They are found in UKIP areas, but are not necessarily motivated enough to vote UKIP. So UKIP strength is an indicator of the presence of shy English nationalism, and it is in these places that the Tories’ anti-SNP message drew a response.

“As well as myself have argued,” is that typical use these days? What is wrong with “As well as I have argued?”

This doesn’t really make a lot of sense. In Clacton and Rochester, increases in the shares of all the parties bar UKIP and most notably increases in the Tory share when they were the challengers against UKIP incumbents surely ought to suggest the very opposite of the article’s conclusion. Shy nationalists in those seats weren’t shy in their 2014 by-elections. They were out and proud UKIP-voters. Cameron made little to no concession to UKIP during the course of the campaign. If anything, what we saw there were shy ex-English nationalists.

Given the general collapse of LibDem votes almost everywhere coupled with large UKIP vote shares putting them second in over 100 seats, the Tory victory would seem more likely to be due to LibDem voters switching to the Tories (left-leaning ones having left years back) or UKIP (where they voted in 2010 on a “neither of the 2 big parties” protest and still wanted to protest).

This LD blog http://aviewfromhamcommon.blogspot.co.uk/2015/05/why-did-lib-dem-voters-switch-to-torys.html gives a plausible reason why LD voters would have gone Tory – they’d stuck with the LDs through the coalition because they liked the coalition and LD contribution to it and come last week preferred Cameron as PM to a LD coalition with Labour or Labour governing with the SNP.

I bet Ms Wareham is your average Labour voter ,the ones who pour scorn on “less educated communities”

Nuff said

“tend to live in rural, less educated communities ..” Nuff said.

Woah. Too edgy for me, madam.