The British government has been frustrated by the hard negotiating line pursued by the EU under the lead of Michel Barnier, and the unusual degree of unity in supporting the EU’s Brexit negotiation strategy has surprised quite a few observers. Drawing on recent survey evidence, Stefanie Walter reflects on the Brexit process through EU-27 eyes, and concludes that by and large Europeans support the EU’s negotiating strategy.

The British government has been frustrated by the hard negotiating line pursued by the EU under the lead of Michel Barnier, and the unusual degree of unity in supporting the EU’s Brexit negotiation strategy has surprised quite a few observers. Drawing on recent survey evidence, Stefanie Walter reflects on the Brexit process through EU-27 eyes, and concludes that by and large Europeans support the EU’s negotiating strategy.

So far, there has been remarkable unity among EU member states over Brexit. While the unwillingness of EU-27 governments to break ranks has a variety of sources, one possible explanation is public opinion in the remaining member states. Surprisingly, although there has been extensive polling on what the British public thinks about Brexit, much less attention has focused on the Brexit-views of Europeans in the remaining member states.

This blog post, therefore, sheds light on the question of what voters in the EU-27 think about Brexit and the Brexit negotiations. It is based on an EU-wide online poll designed by myself and conducted by Dalia Research for the University of Zürich in July 2017. The sample consists of 9,371 working-age respondents (ages 18-65), drawn across the remaining 27 EU Member States, with sample sizes roughly proportional to their population size.

This data shows that Brexit is an issue that a majority of Europeans care about: 46 per cent of the Europeans surveyed said that they followed Brexit a little, and 18 per cent expressed a strong interest in Brexit (compared with 42 per cent and 37 per cent, respectively, in the UK). To the extent that domestic public opinion constrains the negotiation space of the EU-27 governments, it is thus worthwhile to examine what EU-27 citizens think about Brexit.

To this end, I will focus on three questions:

- Does the EU public support the hard negotiating stance pursued by the EU in the Brexit negotiations?

- How do EU citizens evaluate the effects of Brexit on the UK, the EU, and their own country?

- To what extent do spillover effects exist between the Brexit negotiations and exit preferences in other member states?

Does the EU public support the hard negotiating stance pursued by the EU in the Brexit negotiations?

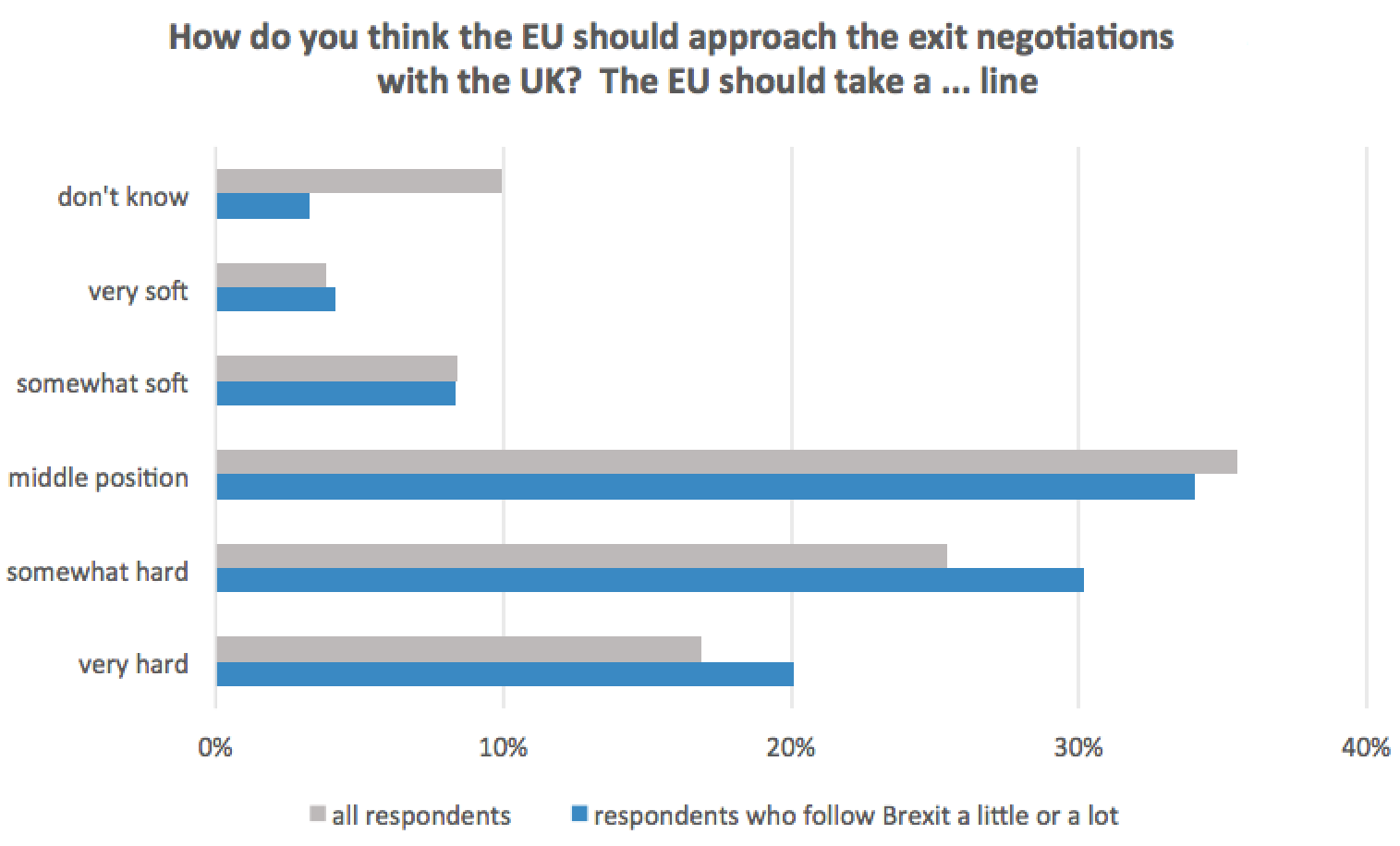

Overall, the European public seems to agree with the uncompromising line of the European Commission on Brexit. A plurality of respondents (42 per cent) favour a somewhat or very hard line. This means that they think the EU should insist that the UK pay a large “exit bill” to compensate for the costs of Brexit, guarantee special rights for EU citizens living in the UK, and should not give the UK privileged access to the European single market. The preference for a hard stance increases the more interested respondents are in Brexit. Among those who follow Brexit a lot, almost two-thirds (62 per cent) support a hard line. In contrast, only 12 per cent of respondents think that the EU should approach the exit negotiations with the UK with a soft line, defined as accepting a small “exit bill,” limits on the rights of EU citizens currently living in the UK, and privileged access for the UK to the European single market.

Figure 1: Public opinion on the EU’s negotiation strategy in the Brexit negotiations

Source: Compiled by the author

Despite some differences across countries, the support for a hard negotiating position is also strong when we look at individual countries. Figure 2 shows the results for the five largest EU-27 countries. Support for a soft line is low in all of them, and with the exception of Poland, a hard line is the most popular negotiation strategy. Among those who are interested in Brexit a lot, those in favour of a hard line even constitute a majority in all five countries, including Poland. Moreover, contrary to the hope of some leading Brexiteers that Germany and Spain would lobby in the UK’s favour lest jobs in the German car or Spanish tourism industry be lost, the German and especially Spanish public is taking a rather hard line: 48 per cent of German respondents and 62 per cent of Spanish respondents support a somewhat or very hard EU position in the Brexit negotiations.

Figure 2: Preferred EU negotiation strategy in the five largest EU-27 states

Source: Compiled by the author

These findings suggest the current EU negotiating strategy pursued by Michel Barnier is based on a broad consensus among the EU public. From this perspective, it is not surprising that British attempts to bypass the EU institutions by appealing directly to EU leaders have failed, or that Brexit is not a highly contested issue in the remaining part of the EU.

How do EU citizens evaluate the effects of Brexit on the UK, the EU, and their own country?

The economies and societies of the UK and the remaining 27 EU member states are strongly intertwined. Brexit will thus invariably affect everyone involved in the Brexit process: the UK, the remaining member states, and the EU. But how do the public in the remaining EU-27 states assess these effects?

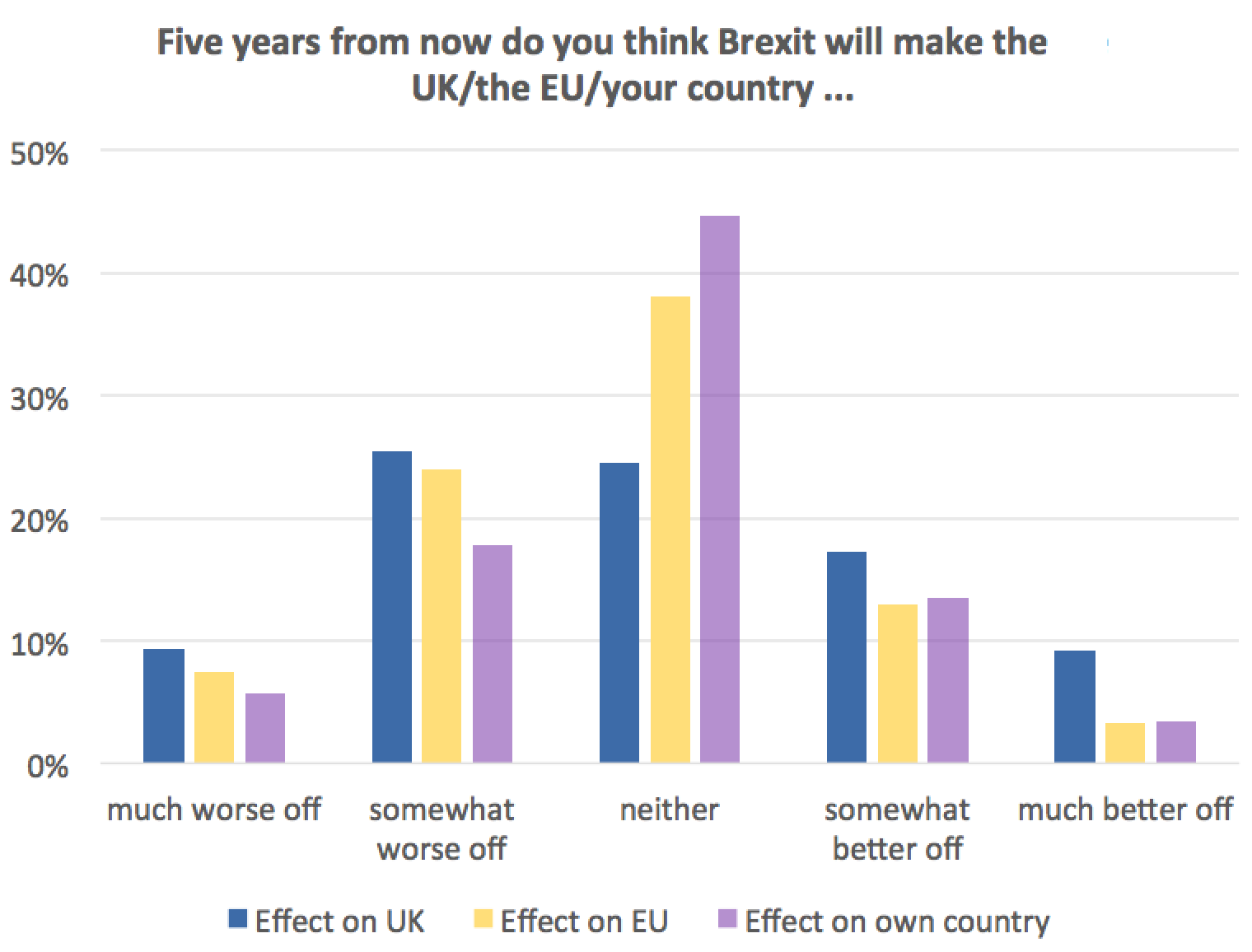

Figure 3 shows what respondents think about the medium-term consequences of Brexit. Three findings stand out. First, many Europeans do not think that Brexit will bring significant changes over the next five years, especially not outside the UK. Less than 20 per cent of respondents think that Brexit will make the UK, the EU, or their own country much worse or much better off.

Second, many Europeans are oblivious to their own country’s vulnerability to Brexit: 44 per cent think that Brexit will neither benefit, nor hurt their country, and this rate is the same among those with a strong interest in Brexit. This suggests that public opinion on Brexit could still shift quite a bit as the effects of Brexit become clearer to voters. Finally, to the extent that they do expect Brexit to have an effect, more people see these effects as negative for everyone involved. Nonetheless, a significant number of respondents also see upsides to Brexit, notably for the UK itself.

Figure 3: Expected medium-term effect of Brexit on the UK, the EU, and respondents’ own country

Note: Due to the presence of ‘don’t know’ responses, the percentages do not add up to 100.

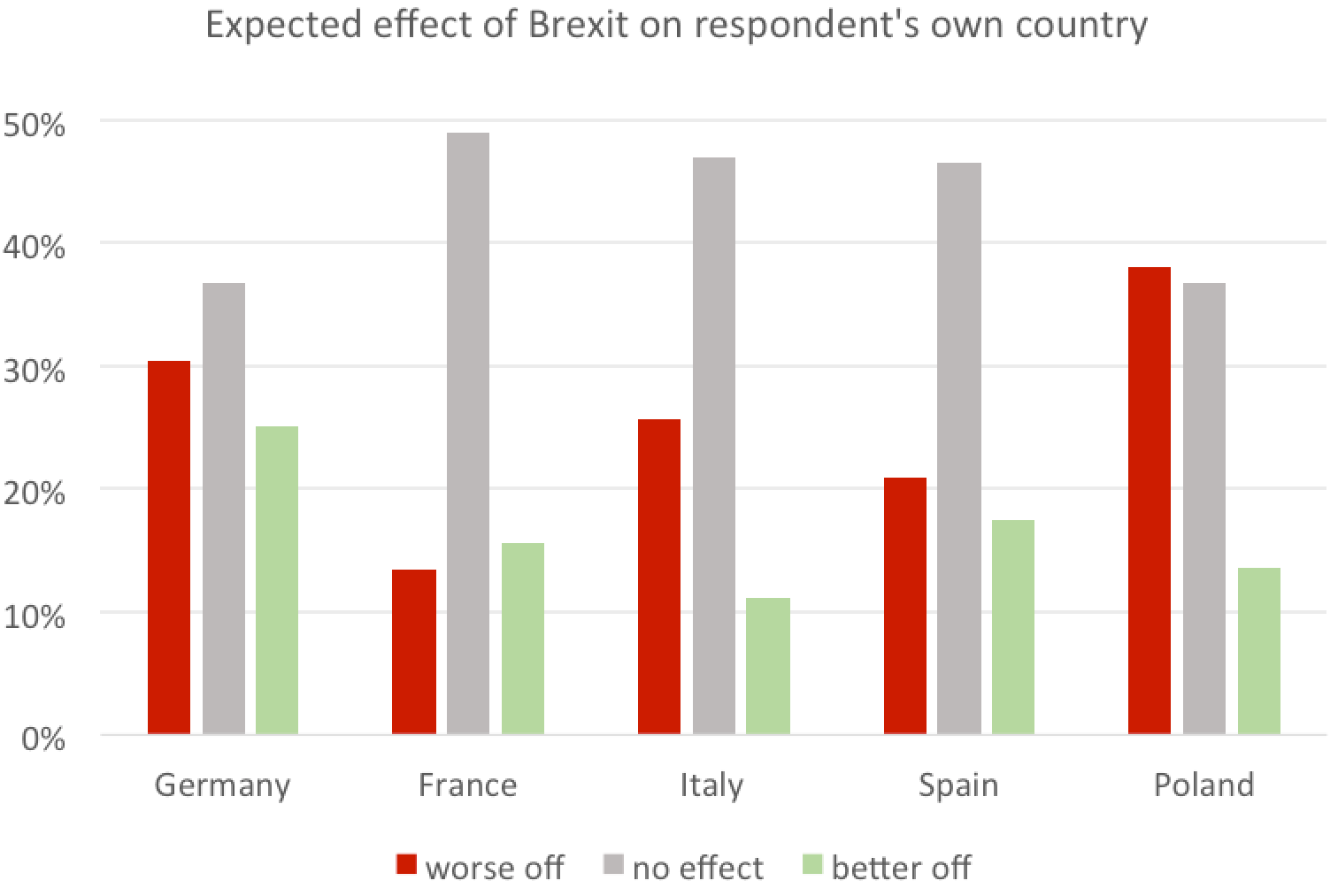

Yet this also masks considerable differences among the EU member states. Figure 4 shows that in some countries, such as Poland and Germany, the public is quite aware of the possible negative consequences and opportunities of Brexit for their own country. In other countries, such as France, the opinion that Brexit will not have much effect on the country’s future dominates.

Figure 4: Expected medium-term effect of Brexit on the five largest EU-27 member states

Source: Compiled by the author

To what extent do spillover effects exist between the Brexit negotiations and exit preferences in other member states?

Voters’ expectations about the effects of Brexit matter for the Brexit negotiations because they widen or constrain policymakers’ room for manoeuvre. But they also matter because these expectations (and eventually, the actual trajectory) are likely to feed back into their own assessments about the viability of leaving the EU.

In the negotiations with the UK, the EU-27 governments, therefore, face an “accommodation dilemma“. In principle, as many Leavers rightly emphasise, the EU-27 have strong incentives to grant the UK continued access to the EU’s single market in order to minimise the disruptions of Brexit at home. Yet if this accommodation of the Brexit-vote creates incentives for other countries to leave as well, such a response might put the entire European project at risk in the long run. After all, a sizeable proportion of Europeans (28 per cent in my data) say that they would probably or definitely vote to leave the EU if their own country were to hold an EU-exit referendum. The rationale for the current hard, non-accommodation strategy vis-à-vis the UK is thus rooted in the hope that such a hard line will discourage further efforts at disintegration. But is this hope warranted?

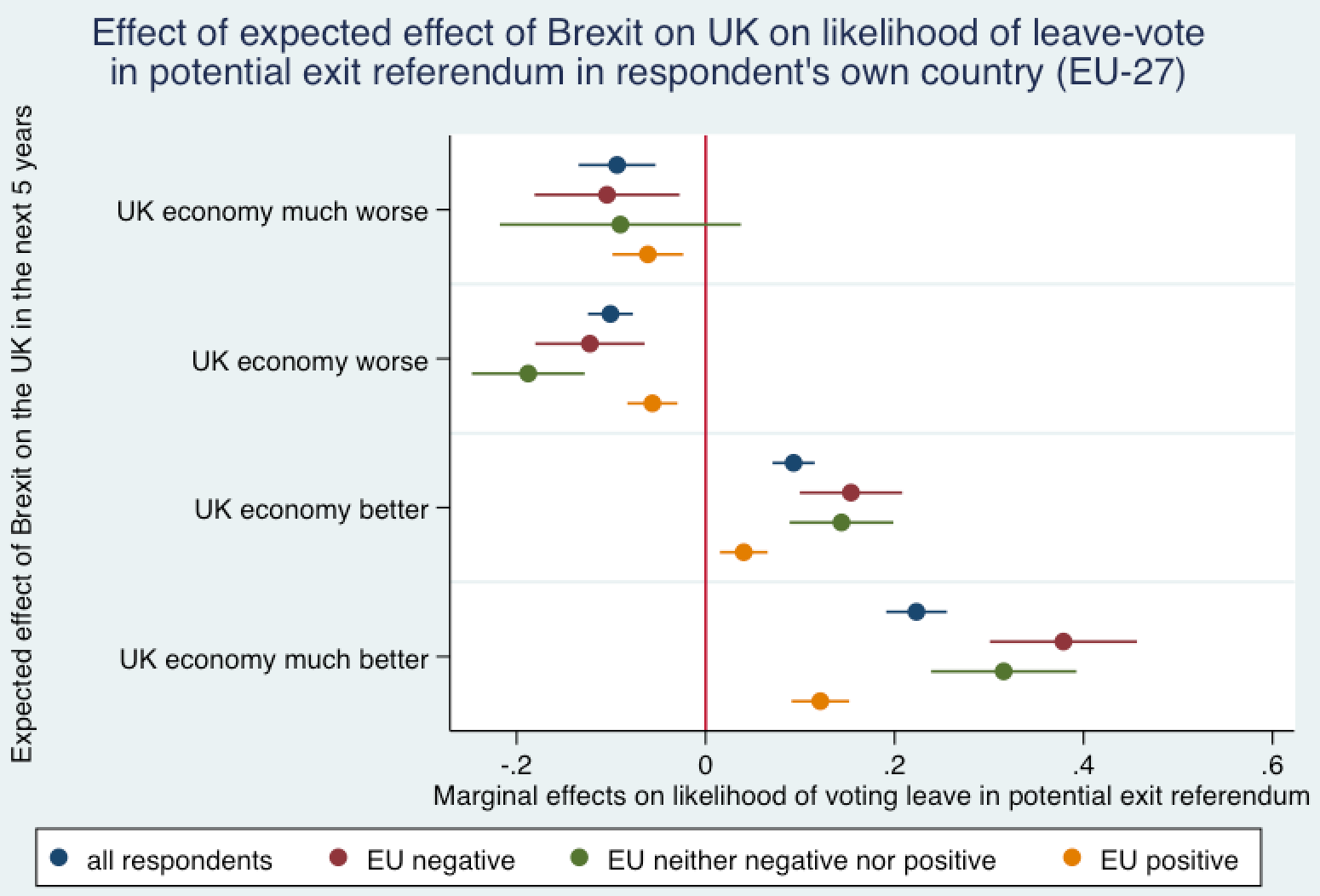

To examine this question, I analyse how respondents’ views about the likely consequences of Brexit for the UK are related to their likelihood of voting leave in a potential exit referendum. Figure 5 shows that those who are more pessimistic about the effects of Brexit for the UK are between ten and twenty per cent less likely to vote in favour of leaving the EU. In contrast, those who are more optimistic about Britain’s prospects outside the EU are much more likely to support an EU-exit of their own country. Notably, this analysis accounts for respondents’ general opinion of the EU – even among respondents with a similar opinion of the EU, differences in expected effects of Brexit translate into different propensities of voting leave.

Figure 5: Link between expectations about the effects of Brexit for the UK and potential leave-vote in other EU-27 countries

Note: The calculation controls for age, education, gender, rural/urban, and country factors. For all respondents there was an additional control for opinions toward the EU.

Because this relationship is most pronounced among those with a negative or neutral opinion of the EU, this suggests that the accommodation dilemma is real. A hard Brexit will hurt the member states. But the remaining EU-27 governments are also right to worry that allowing the UK to have its cake and eat it, too, and to prosper, as a result, risks a profound destabilisation of the EU. Public opinion on Brexit thus matters – but citizens in the remaining member states matter as much for the Brexit negotiations as the British public.

____

Note: This article was originally published on our sister site, LSE Brexit.

Stefanie Walter – University of Zurich

Stefanie Walter – University of Zurich

Stefanie Walter is Professor of International Relations and Political Economy at the University of Zurich. Her research focuses on topics related to globalization, international financial crises, and public opinion. She is the author of “Financial Crises and the Politics of Macroeconomic Adjustments” (2013, Cambridge University Press).

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Well the British being europeans, we are part of the continent of europe certainly support so called hard brexit, or leave as it is better known, rather than so called soft brexit or remain in all but name. There is more to Europe than just the e, not all european nations are in the eu so to say europeans is an incorrect assumption.

I am sorry to say that this sort of survey is totally irrelevant due to the fact that most respondents can’t possibly know whether Britain or their country will benefit or lose out when Britain eventually leaves.

Did the respondents in Germany for example know how much trade they would lose with Britain if we raised tariffs on all their exports here and how many jobs would be lost in the process? My guess is no.

This graph might help us understand who the winners and losers might actually be:

https://fullfact.org/media/uploads/March%202017%20Trade%20with%20other%20European%20countries%20RB.jpg

What we can safely say is that in the short term, Britain will suffer and Europe so will Europe, but in the long run as Britain is a net importer we can and should use the state machinery to direct investment where it is needed and not as we have done in the past wait for market theology to to work in our favour.

The breakup of Europe will depend on the outcomes in this IMF document, meaning that as things get worse so tensions will grow and the EU won’t be able to shrug the negative impacts off.

https://fullfact.org/media/uploads/March%202017%20Trade%20with%20other%20European%20countries%20RB.jpg