Prime Minister Theresa May has delivered her long-heralded Brexit speech in Florence. Thomas J Leeper (LSE), Tim Oliver (LSE/EUI), Holger Schmieding (Berenberg), Katy Hayward (Queen’s University Belfast) and James Dennison (EUI) analyse what it changes – if anything – about the deadlocked negotiations and the indecision at home about what form Brexit should take.

_________________________________

While the Prime Minister continues to be vague on most of the particulars of the UK’s negotiating position, she did commit to a reasonably new idea of what a “good deal” should look like and, more importantly, when and how it should come about. Thomas J Leeper (LSE Government) argues that unfortunately for her and for Britain, the speech is unlikely to satisfy anyone.

While the Prime Minister continues to be vague on most of the particulars of the UK’s negotiating position, she did commit to a reasonably new idea of what a “good deal” should look like and, more importantly, when and how it should come about. Thomas J Leeper (LSE Government) argues that unfortunately for her and for Britain, the speech is unlikely to satisfy anyone.

The PM’s proposal is to enact Brexit in name: to have Britain leave the European Union by March 2019. Her proposal for the specifics of what that might look like, however, appear to resemble much more Britain’s current standing as a full EU member than the conditions of an independent country. She called for creativity in negotiating a long-term new partnership between Britain and the EU during an implementation phase that would see a full incorporation of EU regulation in British law, some degree of legal accountability to the European Court of Justice, essentially unchanged trade terms, and increased control on immigration of the EU. Is this what citizens meant when they voted to leave? And if it is not, will it at least appeal to some of those who voted to remain? I suspect all will be unhappy.

Critics hopeful of a deal are likely to point out that this is, in effect, kicking the can down the road. None of the trickiest issues – trade, freedom of movement, the status of the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland – will be resolved. They will simply be postponed. Critics hopeful of a swift exit from the EU are similarly likely to point out that an extended implementation phase that effectively perpetuates close ties to the continent is not really in the spirit of their referendum vote.

This speech is unlikely to satisfy either constituency and it is hard to imagine that the EU negotiators will find much value in it either. Britain, therefore, continues strongly on a path to “no deal,” which the PM reiterated would be better than anything else.

Dr Thomas J. Leeper is an Associate Professor in Political Behaviour in the Department of Government at LSE.

_________________________________

This speech contained nothing substantively new, says Tim Oliver. It signals to the rest of Europe that it needs to prepare for a hard Brexit – perhaps even no deal at all. Britain has committed the strategic error of picking a fight it will struggle to win.

Much has been made of Theresa May’s choice of Florence to deliver a speech intended for the rest of Europe. She was right to point to the historical links, not least in trade, that bind the UK and the rest of Europe together and of which Florence was once the heart. But it didn’t escape the notice of those attending that the venue was a dreary former Carabinieri training college with views of Florence’s main railway station. In a city overflowing with world-renowned first-rate venues she spoke in a nondescript, fourth-rate one that most in the city have rarely if ever noticed. The Italians hardly seemed to have rolled out the red carpet for her. Optics aside, did the rest of the EU hear what she had to say?

For those elsewhere in the EU not transfixed by the German elections, the response will be disappointment and a growing realisation that they need to prepare for a no deal, hard Brexit. Yes, the Prime Minister spoke of the need for a transition period, of paying contributions, of guaranteeing the rights of EU citizens, and dealing with the question of Northern Ireland’s borders. On closer inspection, however, there was nothing substantively new and she continues to try to bridge differences within the Conservative party rather than between the UK and the EU. Both sides will push forward with negotiations, but a plan B will now be on the rest of the EU’s agenda.

This all reflects how the UK’s overall strategy for Brexit has been a failure to set out realistic and clear ends, think of plausible ways to reach those ends, and configure the means to do so. The British government needs to reflect on what the ancient Chinese general Sun Tzu argued in the 5th century BC: ‘The victorious strategist only seeks battle after the victory has been won, whereas he who is destined to defeat first fights and afterwards looks for victory’. In other words: only seek a fight when you’re sure – or as sure as you can be – that you’re able to win. Those destined to lose get into a fight and then try to think of how to win. Having jumped headlong into Article 50 negotiations without a coherent strategy, Britain has struggled to find a way out of the fight it’s in. The prospects do not look good. That’s not something the EU or anyone should welcome.

Dr Tim Oliver is an Associate of LSE IDEAS and a Jean Monnet Fellow at the European University Institute.

_________________________________

Slowly, slowly, the British government is getting real about Brexit. Theresa May’s Florence speech marks another modest step in that direction, argues Holger Schmieding.

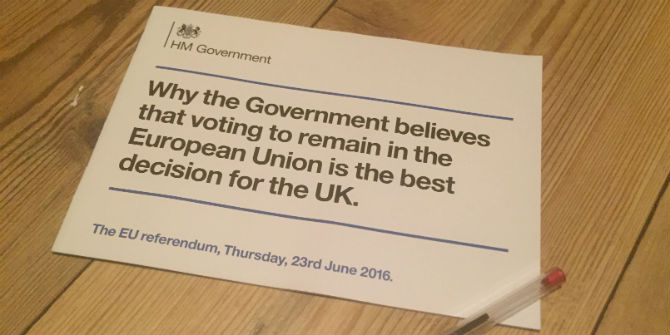

After a referendum campaign in 2016 in which blatant distortions of the truth had carried the day, the United Kingdom is on the way towards acknowledging the facts of life in Europe.

The facts are simple:

- Upon leaving the European Union on 29 March 2019, the United Kingdom will have to honour the legally binding commitments it had willingly incurred as a member. That includes financial commitments.

- Any country that wants to gain or preserve privileged access to the greatest common market in the world, the EU Single Market, will have to play by the established rules of that market.

- In negotiations between a disunited UK and a fairly united EU27 with five times the economic clout of the UK, the EU will largely prevail.

- If the UK wants to avoid a cliff-edge Brexit, it will need a transition period. Negotiating the details of any future arrangement between with the EU is far too complex to be achieved by late 2018 for ratification by March 2019. And in that transition period, the UK will have to abide by EU rules.

Even more important than what Theresa May said is the implicit admission that came with her giving the speech at all: in the Brexit talks, the EU sets the agenda. Britain first has to tackle the thorny issues of divorce before it can proceed to the details of its future trade arrangements.

On substance, May moved the UK position modestly towards the inevitable: Britain will have to pay up. The offer of continued payment into the EU budget during a two-year transition period – which will amount to around €20 billion – marks a departure from previous prevarication on the issue. However, it only takes the UK halfway towards the €35-40 bn which the EU will almost certainly demand as a minimum to cover the UK’s legacy liabilities during a post-Brexit-transition period and beyond. On the rights of EU27 citizens in the UK, and UK citizens in the EU, May’s tone was more constructive than before. As always, the devil will be in the details, though. Unless UK chief negotiator David Davis unexpectedly presents the EU27 at the next round of negotiations next week with detailed explanations that satisfy EU27 demands, the EU will not be willing to move on towards a discussion of post-Brexit trade relations at its upcoming summit on 19-20 October.

For her listeners on the European continent, May’s choice of venue for her speech carried a message which she may not have fully intended: like no other city, Florence stands for the renaissance of Europe after the dark ages before. Indeed, with firm economic growth ahead of that in the Brexit-stricken UK and with renewed reform momentum, the Eurozone and the EU are enjoying something like a renaissance. Partly due to the offputting examples set by Donald Trump and – less significantly – Boris Johnson, even many of the continent’s pesky protest parties such as France’s Front National or Italy’s 5 Stars are turning away from demands to break up the EU or the euro. This renaissance makes the Brexiteers look even more isolated in Europe than they were before.

Dr Holger Schmieding is Chief Economist at Berenberg in London.

_________________________________

The PM notes that “lives”, as well as livelihoods, depend on being able to protect the “progress made in Northern Ireland” throughout the withdrawal progress. The stakes could not be higher, warns Katy Hayward (Queen’s University Belfast). Yet the substantive contents of this speech represent a further retreat from the principles and position needed to prevent Brexit causing real harm to this fragile region.

The PM notes that “lives”, as well as livelihoods, depend on being able to protect the “progress made in Northern Ireland” throughout the withdrawal progress. The stakes could not be higher, warns Katy Hayward (Queen’s University Belfast). Yet the substantive contents of this speech represent a further retreat from the principles and position needed to prevent Brexit causing real harm to this fragile region.

The one specific mention of the Irish border in this speech was to state that “we will not accept any physical infrastructure at the border”. From “seamless and frictionless”, to “as frictionless as possible”, to, now, not having “physical infrastructure” – it is deeply worrying that the language of the UK government on this subject has got more and more miserly as the clock has ticked on.

May’s government still only appears to see barriers to trade when they take the form of a border checkpoint or tariffs. “When it comes to trading goods we will do everything we can to avoid friction at the [UK/EU] border”, May soothes. But, we repeat, an invisible border does not by any means equate to a soft border, let alone an open one.

For this speech embodies assumptions and notions that directly negate any attempt by May to foster the ‘trust’ she is asking for from the EU. Indeed, she makes it quite clear (despite the rhetoric of working ‘hand in hand’ or ‘side by side’): the two are on different trajectories now.

“There will be areas which do affect our economic relations where we and our European friends may have different goals; or where we share the same goals but want to achieve them through different means.”

“When we differ from the EU in our regulatory choices, it won’t be to try and attain an unfair competitive advantage, it will be because we want rules that are right for Britain’s particular situation.”

Why is this so concerning for Northern Ireland? The 1998 Agreement conceived of Northern Ireland as a bridge between the UK and Ireland; after Brexit, it will form a bridge between the UK and the EU. May claims that the favoured prize of this negotiation will be: “A sovereign United Kingdom and a confident European Union, both free to chart their own course.” As the two blocs do just that and head into different waters, this small region could plunge and drown in the growing schism between them.

This is why specific arrangements to meet Northern Ireland’s unique political, social and economic circumstances are vital. And it is why “avoiding physical infrastructure at the border” is nowhere near sufficient to protect the “lives and livelihoods” put at risk here by Brexit.

Dr Katy Hayward is Reader in Sociology & Senior Research Fellow, Senator George J. Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice at Queen’s University Belfast.

________________________________

May’s Florence speech was part of the Conservatives’ post-referendum strategy of detaching her from the day-to-day Brexit negotiations and restricting her interventions to resolving logjams and discussing high-level goals, writes James Dennison (EUI). It was logical to dangle British security cooperation as a prize. But very little has changed since her Lancaster House speech, which betrayed the usual British indifference to Europe’s priorities.

May’s Florence speech was part of the Conservatives’ post-referendum strategy of detaching her from the day-to-day Brexit negotiations and restricting her interventions to resolving logjams and discussing high-level goals, writes James Dennison (EUI). It was logical to dangle British security cooperation as a prize. But very little has changed since her Lancaster House speech, which betrayed the usual British indifference to Europe’s priorities.

May’s decision to speak in Florence raised enough eyebrows, but to then whitewash the city’s splendour by speaking in front of a blank screen hinted at the Brits’ long inability to appreciate continental Europe, let alone European integration.

She initially outlined what the British offer to Europeans mostly in terms of Britain’s considerable military and intelligence contribution to the defence of the continent. This is a logical strategy. The status quo whereby many continental countries free ride under the American-led Western security umbrella—a Cold War hangover—is coming under increasing strain in the Mediterranean and at the Russian border, underlined by the US ‘pivot’ to the Pacific. By adding defence to the Brexit equation, she hopes to place Britain in a stronger negotiating position by reminding EU governments of the need for UK-EU cooperation in all spheres to justify the UK’s defence commitment. However, a future Anglo-European ‘Security and Justice Treaty’ will mainly appeal to national governments and less to EU officials, somewhat mirroring British misunderstanding of the Union’s modus operandi hitherto in the negotiations.

On trade, May dismissed EEA membership or any largely ‘rule-taking’ relationship as unsustainable in the long-term due to the lack of political support in the UK. In doing so, she implicitly admitted this might be the short-term, transitional outcome. She also argued that a Canadian-style agreement would be wastefully suboptimal given the existing regulatory harmony between the UK and EU. As such, a new court to which both the EU and UK send judges as equals seems to be May’s solution to resolving regulatory disputes. Another option would be to have UK judges interpret EU law in the UK—requiring the type of act of faith by the EU that the UK always felt so uncomfortable with. She also aimed to increase business certainty by pushing for a ‘double lock’ on transition and its deadline date.

Unsurprisingly, there was fairly little detail in the speech and little change in the government’s negotiating stance since Lancaster House, besides details on the transition and meeting existing budgetary commitments. Depressingly, May mostly took questions from British journalists, always on first name terms, with just two nods to an Italian and German journalist. With 18 months to go, most public statements on the negotiations, including this one, remain very much for domestic audiences and political calculations from both sides. By contrast, the European Commission’s Joint Technical Notes suggest significant progress on detail behind the scenes. Let’s hope so, because a disorderly Brexit would be terrible news for both the politically volatile UK and the still crisis-ridden EU.

Dr James Dennison is a Research Fellow at the European University Institute in Florence.

_________________________________

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Great analysis from academia, though I expect the usual suspects drinking the Brexit cool-aid in the British media may be oblivious to how vacuous the speech was. May explicitly mentioned that she would like a relationship with the EU that is deeper than a mere FTA like Canada’s but also that allows the UK more flexibility than a relationship like Norway’s and the Association Agreement of the EEA, and then had the gaul to ask the EU to “be creative”; in essence asking the EU to design a way for the UK to have its cake and eat it. The substance of the speech contradicted her message that she understood that the UK couldn’t have benefits without obligations.

Katy Hayward’s analysis is spot on.

Underlying all of these political decisions is the unquestioned paradigm of neo liberal globalisation which is a philosophy that entirely effaces embedded local cultures save to harness them to their economic models, usually as a cobbled afterthought.

In the case of Northern Ireland, the effaced embedded cultures are those of a deeply criminalised underbelly of economically excluded working class which is only kept in check by the hard sectarian parties wielding both soft, as in Stormont MLAs, and hard power over them, as in the ubiquitous housing estate paramilitary vigilantes that the PSNI leave to police these ‘problem’ areas.

If the Westminster/DUP model of a hard Brexit is effectively imposed upon a Northern Ireland most of whose citizens voted to remain in the EU, and there is every political indication that this will now occur, there will not be return to the old style violence of the Troubles era, save on the fringes of the borders of the Rebublic which are heavily policed, but rather a ‘ unforeseen’ frighteningly fast spill over of disintegration of any semblance of civic law and order from these unpoliced wild west gangland areas into areas now deemed safe to live in.

For those to be affected by this predictable post hard Brexit increase in localised chaotic violence, expect the ruling DUP and the British government to use it to further their prosperous political careers through a combination of victim blaming and tired inappropriate bigoted political finger pointing.

What a shameful shambles.

I was struck by how UK-centred the approach of Theresa May was. I always understood that a good general gets inside the mind of his opponents, not his allies. This speech simply kicks the ball down the road. Instead of a cliff edge in March 2019, we have a cliff edge two years later.

A more imaginative approach might have been to suggest EEA membership in the transition period, rather than sticking with the status quo. However I am no expert on the EU, so defer to the experts on the reasons for this.

I know that the EEA option is promoted, even by members of the cabinet but personally I do not see how it will be acceptable to a sizeable number of the members of the EU and their signatures need to be on the agreement. The reason being no fish or agriculture. Macron is not going to nip upto the Northern ports and say you are all unemployed and then take the TGV to the wine areas and say you are going bankrupt. The Irish have already said that the UK must stay in the customs union (this means staying in the whole EU) because their agricultural exports must be protected. Then their is the Spanish, Dutch, Danish and Eastern Europeans.

IMO both sides need to face facts the only deal is the UK out with an FTA.