How does an obscure article in the Lisbon Treaty obfuscate Britain’s efforts to formulate a post-Brexit relationship with the European Union? And what does this have to do with dead parrots? Monica Horten explains below.

How does an obscure article in the Lisbon Treaty obfuscate Britain’s efforts to formulate a post-Brexit relationship with the European Union? And what does this have to do with dead parrots? Monica Horten explains below.

It was Margaret Thatcher who famously replayed Monty Python’s ‘dead parrot’ sketch at the Tory party conference 28 years ago in 1990. Then the Conservative Party gathered in Birmingham for its annual get-together the other week, it would seem a dead parrot was once again at the centre of the debate. It’s well-known that Mrs Thatcher did not know who or what Monty Python was when she spoke their lines. Today, Mrs May is struggling with what increasingly seems to be a stiff, lifeless parrot. She maintains that her Chequers proposal is the only option.

The Chequers proposal sets out the government’s position for Britain’s future relationship with the European Union after Brexit with regard to future trade and security arrangements. The Chequers proposal splits out trade in goods from trade in services, and puts forward the notion of “common rulebook” which is problematic. Domestic politics have conspired against Chequers. Many commentators, including the chair of the Treasury Select Committee, Nicky Morgan have said that Chequers is dead. There’s no support for it from those who want Brexit, or those who don’t want it. That means the Parliamentary arithmetic will not work and there is no way it could get a majority.

The EU cannot support it because it would break the principle of the Single Market as enshrined in the Treaties, and its negotiator, Michel Barnier, is bound by the Lisbon Treaty – Article 207(3): The Council and the Commission shall be responsible for ensuring that the agreements negotiated are compatible with internal Union policies and rules. It would seem that the Chequers proposal is being nailed it to its perch by the government which is seeking to perpetuate it as a living organism. And so various political actors are trying to come up with alternatives.

The parrot in the Monty Python sketch was a Norwegian Blue. Some MPs are calling for the Norway option to be revived. This is where the UK would leave the European Union and become like Norway, a Member of the European Economic Area (EEA), giving it full access to the Single Market (See the full EEA Treaty in EU Official Journal Volume 37 L1 1994). However, Norway still has to pay into the EU in return for that market access, it must abide by the four freedoms – goods, services, people and capital – and it has no say in EU law, although it must apply it. It also has a raft of bilateral treaties giving it access to various EU agencies.

Nick Boles, Conservative MP for Grantham and Stamford, has drafted a Brexit compromise based on EEA membership. The UK, as a Member State, is a signatory in its own to the EEA Agreement (See page L1/533), however, it is an open legal point as to whether or not the UK may remain an EEA member after Brexit. The most likely interpretation is that the UK could signal its intention to remain in the EEA, whilst leaving the European Union, and if it does so before 30 March 2019, it could legally stay in the EEA. ( See David Allen Green’s post here for a fuller legal analysis ). Stephen Kinnock, Labour MP for Aberavon, has also proposed an EEA compromise.

These positions are supported by Nicky Morgan, chair of the Treasury Select Committee, who pointed out the difficulties of achieving a bespoke deal with the EU, and by implication that the ready-made option of the EEA would be an acceptable compromise. Whilst the Norway model might have a been a practical option to explore in the summer of 2016, it could be tricky to get it through now. If we assume the legal analysis is correct and we could just ask to retain the EEA membership in our own right, there will still be additional agreements to be drafted around how much we pay for market access, and bi-laterals put in place to address our membership of EU agencies such as the European Medicines Agency, or GNSS agency that runs the Galileo satellite programme. These agreements could be done, but they would take time – longer than the six months left until the March 29 deadline. The loss of influence at the top table of arguably the world’s most powerful regulatory bloc, is a serious consideration for the UK.

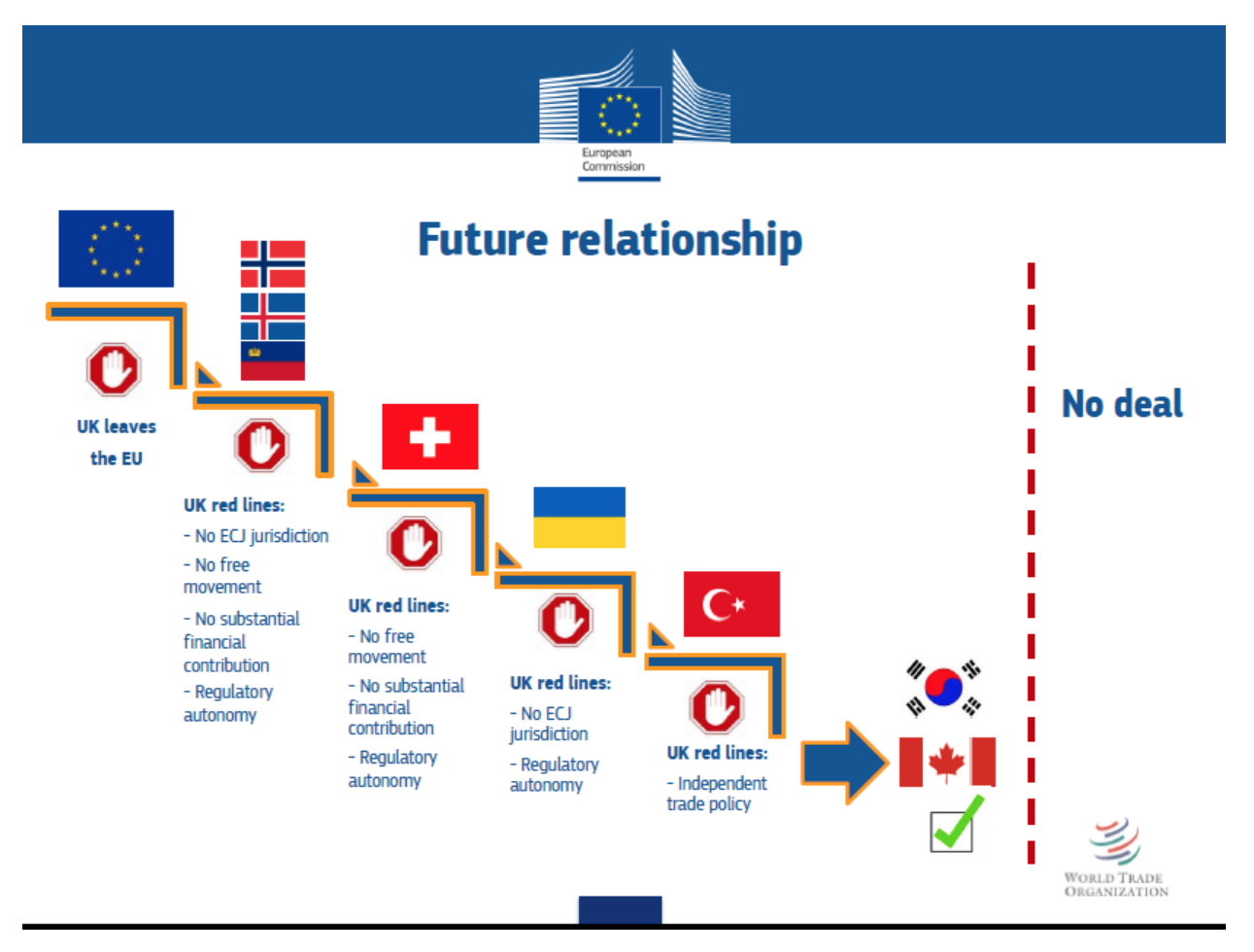

As things currently stand, the Parliamentary arithmetic for the Norway model in the UK is unclear. Nicky Morgan claims there is a majority for this model. The Norway parrot will only fly if that view proves correct. The other alternative is the so-called Canada model. However, beware that there are two Canada models. The first Canada model is the 454-page Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) signed between the EU and Canada, and which the UK, as a Member State, currently benefits from. David Davis said the EU offered it some time ago: this is what they meant. Here is Michel Barnier’s slide presented to the European Council of Ministers on 15 December 2017.

CETA took 7 years to negotiate. It includes chapters on some elements that the UK would want such as telecoms and e-commerce, but these provisions give us nothing like what we have inside the EU Single Market. It also includes provisions on raw materials such as minerals and metals, which are of interest to Canada, but arguably less applicable to the UK’s service-driven market. It also provides an exception for culture, so cutting out audio-visual services, another important industry for the UK.

Hence, any agreement based on that “Canada model” would need significant modification to give the UK what it has today. The EU is unlikely to do this, because it cannot give us a vastly better deal than it has given to Canada and other countries such as Japan or Korea. Philip Hammond, Chancellor of the Exchequer, speaking on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme, dismissed the idea of a Canada model. Moreover, such an agreement would have to be negotiated in detail after the UK leaves the EU. Negotiations would begin after March next year. The risk is that there would be nothing in place for many years.

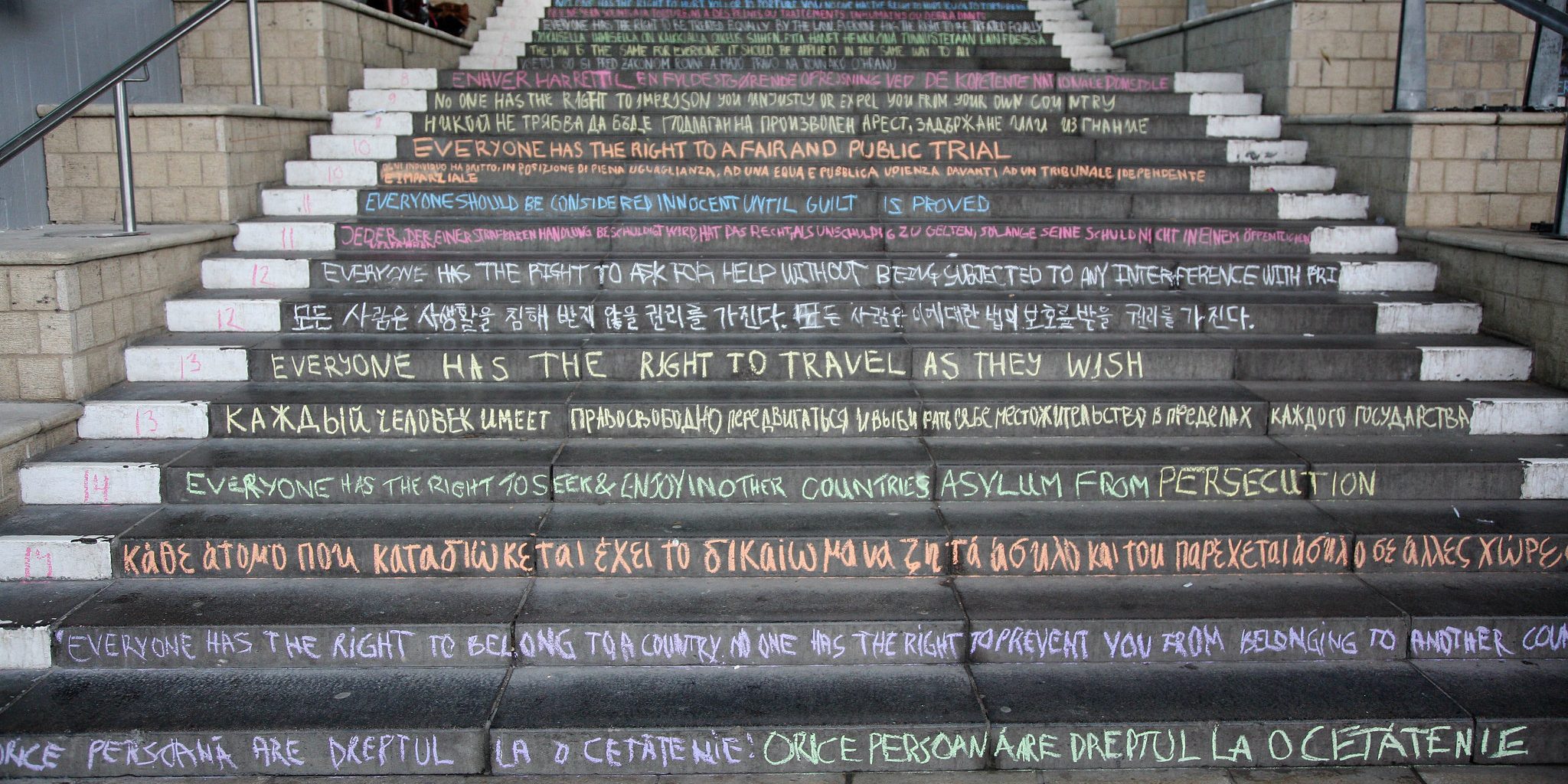

Image by DAVID HOLT, (CC BY 2.0).

Image by DAVID HOLT, (CC BY 2.0).

The second “Canada model”, dubbed ‘super-Canada’ was advocated by Boris Johnson in his Daily Telegraph article. This ‘super-Canada’ is what in the software industry is known as vapourware. Mr Johnson’s article contains much emotive rhetoric, but where is the substantial detail that one would expect in a serious policy proposal? For example, evidence, policy papers, working documents, consultations, working group reports and so on from the relevant government departments. These are all missing.

The so-called ‘super’ deal is set out In just eight bullet points. It calls for zero tariffs and zero quotas on all imports and exports with the EU, and it calls for extensive provisions on services. The article omits to say that we have that now, in the Single Market, and that as a third country negotiating a trade agreement with the EU, we will have to re-negotiate all those tariffs and quotas, sector by sector. Moreover, a quick check of CETA reveals that its services provisions are thin compared with what we have in the Single Market.

The article conflates the model of an actual free trade agreement that is CETA with a hypothesis of various theoretical positions and actions that the UK ‘could’ take in future – a hypothesis that is US-centric. The proposal draws on a paper published by the free market think tank Institute of Economic Affairs. The IEA paper seeks to align the UK with the US, and among other things, calls for moving away from the strictures of the GDPR which implies a shredding of the EU principle of privacy protection.

The underlying issue with ‘super-Canada’ is that it seeks to do a deal where the UK could, on the one hand, agree to abide by the high standards of regulation – implying that we would stay aligned with the EU–and at the same time, the UK could choose to diverge. For example, it proposes Mutual Recognition agreements:

“In a spirit of trust and common sense we should agree that both UK and EU regulatory bodies are recognised as capable of ensuring conformity of goods with each other’s standards. And it should be easy to draw up Mutual Recognition Agreements covering UK and EU regulations now and in the future – since we all want high standards, and we will all insist on proper protections for consumers.”

And at the same time it wants dispute settlement to address divergence:

“As with any free trade deal between sovereign powers there should be a process for recognising each other’s rules as equivalent, where they are, and a dispute settlement mechanism for managing any regulatory divergence over time. That process of regulatory divergence – one of the key attractions of Brexit – should take place as between legal equals, so that neither side’s institutions have power over the other’s.”

Herein lies an inherent contradiction. It is seeking an agreement of mutual recognition based on trust, and at the same time, it is saying that the UK plans to betray that trust and diverge towards a US-centric framework. Just as with the Chequers proposal, Article 207(3) of the Lisbon Treaty would preclude the EU from agreeing to this. On that basis, the Canada model won’t fly either.

Hence, if Chequers is an ex-parrot, as it would seem to be, and it’s a bit late for Norway, and Canada has no wings, where does that leave the UK?

This article also appeared on Iptegrity and it gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSE Brexit, nor of the London School of Economics.

Dr Monica Horten is a trainer & consultant on Internet governance policy, published author and Visiting Fellow at the London School of Economics & Political Science.

I’m afraid the premise of this article is wrong. Art 207 TFEU is about external agreements. That has nothing to do with the internal market. In practice, the EU has split the freedoms in external FTAs many times. When Barnier and others go on about this, what they mean is that splitting the freedoms risks allowing the third country to undercut EU products and services via cheaper inputs (mainly services, eg access to capital). Important to distinguish the legal from the political/economic in this case.

I beg to differ. This post is about an agreement on trade to be negotiated with the UK as a third country. It is exploring the possible responses from the EU to the different options that are being mooted currently in the UK, After 29 March next year, the UK will be a third country. Article 207 (ex Article 133) is about Common Commercial Policy and it guides the EU in negotiating trade agreements with third countries. The EU is not able to negotiate provisions in a trade agreement that would require changes to its own legal framework.

I am pretty sure that if the departure is without an agreement the people/business of the EU would want the EU to quickly reach a compromise. The EU would implement a border across Eire/NI. After that we can all get back to concentrating on trade with the rest of the world.