The Brexit vote was a challenge to Scotland’s regional autonomy. The country’s response has been to work towards removing itself from the source of its policy preference variation with Great Britain, writes Ryan Lux (University of Texas at Dallas). He argues that this can be explained by physical distance from the political centre, which is London. Both Northern Ireland and Scotland voted to remain in the EU while Wales and England steered toward a break from the institution, he concludes.

In international relations, it is commonplace to analyze the actions of a country by viewing that country as a singular actor. However, we know that multiple groups exist within any country that make up the national preferences. This issue is compounded when the government of a state has subnational governments underneath as the United Kingdom does. In recent interviews regarding the British withdrawal from the European Union, Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has argued for another Scottish independence referendum. In the 2016 Brexit vote, Scotland voted overwhelmingly in favour of remaining in the EU. We know that citizens increasingly desire regional control, yet at the same time, they also want the national policy to reflect their values. Scotland has clearly lobbied for increased regional autonomy over recent years, and been somewhat successful in this area. When an issue occurred that challenged this regional autonomy, the Brexit referendum, the Scottish response has been to work toward removing itself from the source of its policy preference variation with Great Britain.

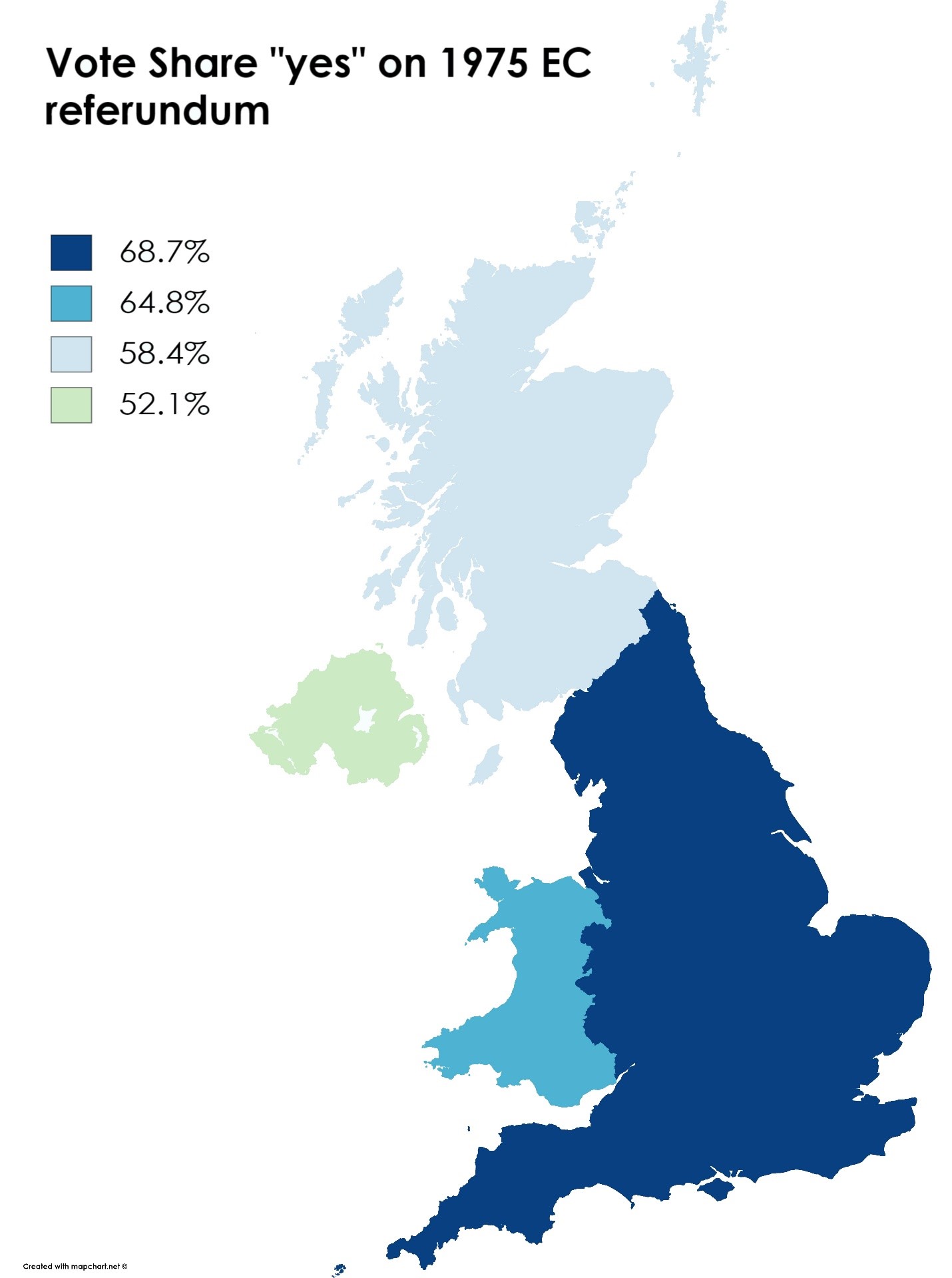

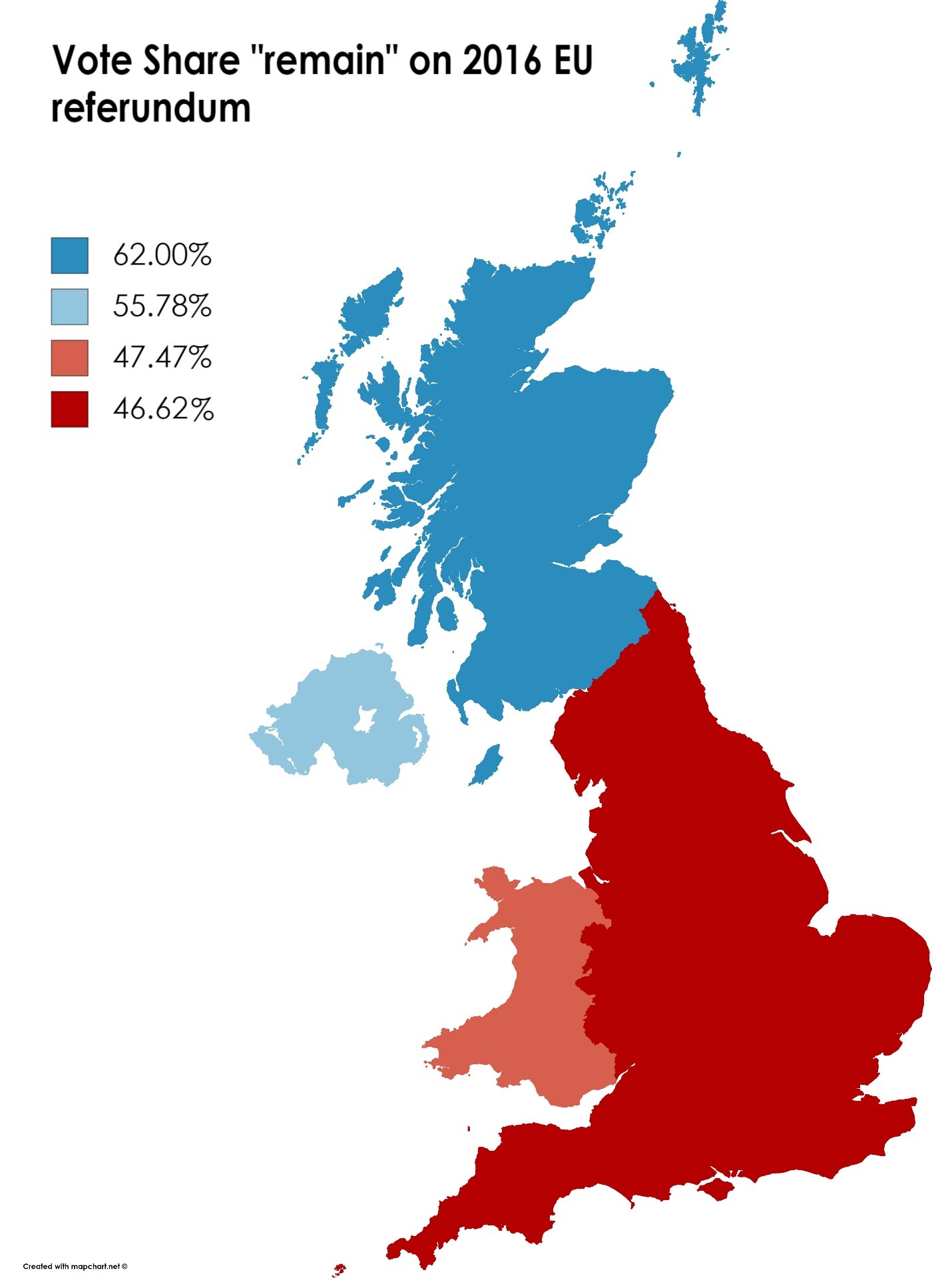

Interestingly, the Welsh vote on Brexit was in line with the British vote. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the vote percentage of each country for joining the European Community in 1975 and remain the EU in 2016 respectively. Both Scotland and Wales have sought increased regional control, yet clearly, they have different policy preferences. So then how can we reconcile these differing situations? Political parties are attributed as contributing to the desire for regional control, as evidenced by the dominance of the UKIP party during the Brexit vote. However, this potential explanation fails to account for another potential determinant, distance. Physical distance from the political center, London, may also have played a role, with both Northern Ireland and Scotland voting to remain in the EU while Wales and England steered toward a break from the institution.

Further complicating the puzzle is the upward directional pull on the UK by the European Union. Granting authority to lower government levels presents a set of challenges for the UK as a whole, while simultaneously dealing with the EU overhead. It would seem that power, or more aptly stated, authority, is being pulled from the British centre in both directions. A natural competition for political power exists, giving an environment in which savvy political parties can play to their voters in many directions.

Party elites drive voter preferences, a fact that is exacerbated as polarization increases. Party leaders use an “us versus them” mentality to frame public opinion. While the central government is the deciding factor in many aspects of foreign affairs, the subnational governments also play a major role. Subnational elite leaders matter in framing the arguments and can either increase or decrease the level of polarization. If we make the analogy to running a firm, centrality is important to the exercise of power. Within an organisation, firms that are closer in proximity to the company’s headquarters exhibit signs of increased control by the governing board. In a similar vein, a region that lies in close physical proximity to the central government unit is subject to the increased exercise of control over that region. Then, as physical distance from the political centre increases, this effect should diminish. This would provide greater latitude and leverage in framing public opinion for the subnational leaders of regions farther from the centre.

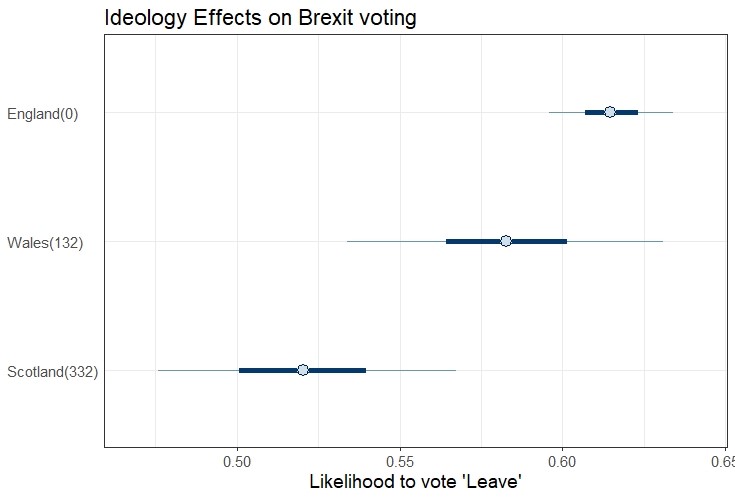

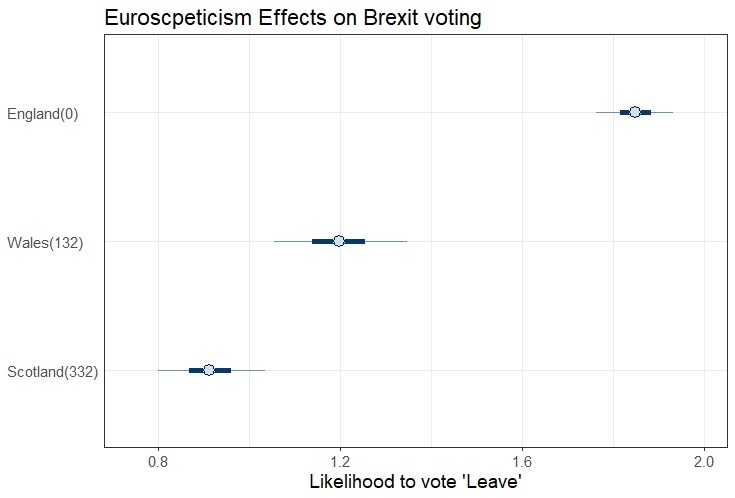

The British Election Study conducted survey interviews between February 2014 and June 2017. Respondents were asked, “If there was a referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union, how do you think you would vote?” Options were vote to leave, vote to stay, or refuse to vote. These surveys provide insight to voter’s decisions on the Brexit vote both before and after the actual vote occurred. These responses are examined with regards to the country from which the respondent comes including a calculation, in miles, of the distance between their political centres. Additionally, respondent’s left-right ideology is examined to determine party influence. Euroscepticism is also added as another potential indicator.

Figure 3 shows that as the distance from London increases, the likelihood of voting to in favour of Brexit decreases when taking into account partisan affiliation. Figure 4 shows similar results, as the likelihood to vote “Leave” decreases the farther a region is from London. Indeed, Euroscepticism has a much higher effect on voting decisions than left-right ideology. Wales and Scotland each exhibit a lesser likelihood of voting to leave across both indicators, although the results remain positive. The effect does not revert entirely to the alternative of voting to remain in the EU. However, the effect is clearly diminished as physical distance increases.

A clear correlation exists between partisanship and the decision within the UK to leave the European Union. This effect is evident as well in regard to Eurosceptic positioning. This relationship also exhibits effects in light of the region’s physical proximity to London. The effect of ideology and Euroscepticism are weaker in Wales than in London, while Scotland shows even weaker effects. Clearly, England exerts more control over Welsh politics than it can Scottish politics, in large part due to physical closeness.

An additional avenue for future research is to collect data regarding Northern Ireland and its citizens’ views on Brexit. Northern Ireland respondents are specifically excluded from the BES survey, which the authors note is due to political circumstances in the country. However, the varying political circumstances are what help to understand the effects of region on policy preferences. The preferences portrayed by Northern Ireland’s respondents, as is the case in Wales and Scotland, are inextricably linked to the political climate within the area. Thus, the Northern Ireland vote to remain in the European Union should not be eliminated from any analysis regarding Brexit.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the LSE Brexit blog, nor of the LSE.

Ryan Lux is a PhD Candidate at the University of Texas at Dallas.

There is much that is questionable about this piece.

There are important questions about geography and distance in the referendum vote and UK politics more broadly. This article, however, fails to address them in a serious way. There are basic errors, such as stating that the 1975 vote was about joining the EEC, which the UK had done in 1973. The vote was therefore, as in 2016, a vote on whether to leave or remain. More troubling is that it makes no effort to look at regional differences within England despite England being 85% of the UK’s population. The piece even begins by pointing out how important it is not to see a country as a singular actor, but then proceeds to do this with regard to England. Instead attention is given to the lack of data about Northern Ireland, which has always been very different to the politics found in Great Britain (I’m also not sure the author understands the differences between GBR and UK). The article shows a disregard for the differences between the terms country, England, regions, London, and political centre, sometime jumping between them and sometimes conflating them to support the argument that proximity to England/London/political centre is an important factor in explaining a vote to Leave. But that leads to the single biggest hole in the argument in that it makes no effort to explain why the voters who live in the political centre/London voted 60% for Remain! This may be because of distance, albeit in this case being one of proximity to political power rather than being distant from it. But the piece makes no effort to think about this or explain it.

Due to the brevity required in this blog entry I was unable to spell out all the details of the argument that is made in the full article. I would like to address your criticisms rather quickly here. First, I am aware that the UK joined the EEC in 1973. I am also aware that this was done by legislative action. Since the piece is focused on individual level preferences, it makes sense to use the 1975 referendum, which serves as a comparison to the modern BES survey data. Second, I apologize for any perceived conflation of terms regarding hierarchical structuring in the article. I do use region and country interchangeably as the UK is comprised of four distinct countries which provide the regional basis for my analysis. This is not an attempt to mislead. I also use the terms subnational unit and subcentral government to refer to those levels below the national level. And finally, the purpose of my article was not to explain why the vote for “remain.” Rather, my article seeks to explain why one area votes in one manner and another differently. I would be happy to provide the full article for you if you would like to examine it further. I would welcome any feedback you could provide.