In 2017 the former Greek Finance Minister Yannis Varoufakis aptly described the Brexit negotiations as a ‘Dog’s Brexit’ and it would appear little has changed. ‘Deal or No Deal’, Brexit will have effects on the British food and drink manufacturers, writes Derek Watson (Sunderland).

In 2017 the former Greek Finance Minister Yannis Varoufakis aptly described the Brexit negotiations as a ‘Dog’s Brexit’ and it would appear little has changed. ‘Deal or No Deal’, Brexit will have effects on the British food and drink manufacturers, writes Derek Watson (Sunderland).

The former British Prime Minister David Cameron’s bravado in rolling the Brexit referendum dice failed to read public opinion, when 52% of the public voted to leave forcing his hand to promptly foreclose on his political legacy. Teresa May a staunch remainder, subsequently stepped into number 10 and grasped the Brexit baton. The Prime Minister’s decision to promptly activate a withdrawal in signing article 50 of the Lisbon treaty with no agreement on an endgame plan, clearly contributed to economic instability. In response, the pound suffered its worst day dropping to $1.3236, a fall of more than 10%. Both the FTSE 100 index and the more UK-focused FTSE 250 fell more than 8%. The drop in British sterling forced the annual inflation rate of 0.5% up to 2.9%. This, in turn, slowed the wage growth into a decline that resulted in a contraction of consumer spending and categorised the UK as the slowest growing economy in the G7.

The Governor of the Bank of England stated that monetary policy cannot prevent the weaker real income growth likely to accompany the transition to new trading arrangements with the EU. The International Monetary Fund is also anxious about the economic unknowns by stating Britain’s vote to leave the EU is already damaging the UK economy. The president of the United States also expressed concerns stating that he would have negotiated Brexit with a “different” and “tougher” attitude than to Theresa May.

Facing a diminishing time lime to the so-called E day, March 29th 2019, government ministers remain divided and have focused more on internal snipping rather than negotiating with Brussels. In an attempt to bring unity, a Venn Brexit Deal, namely the ‘Chequers Plan’ was hatched in order to gain support from her party and Brussels. Whilst the final 582-page proposal has been accepted by the EU27, it has caused turmoil in Westminster with 7 ministerial resignations. To further undermine the proposed agreement, the message from the Bank of England and the Chancellor stated that the UK would be ‘economically’ worse off it exited from the EU. Such sentiments were also echoed by Donald Trump in stating that the UK “may not be able to trade with us”.

Image by David Jackmanson, (CC BY 2.0).

Image by David Jackmanson, (CC BY 2.0).

It was not just the currency traders who were caught on the back foot as businesses are also anxious about the future. The food and drinks sector is equally apprehensive and is a key player in the UK economy, contributing over £28bn a year. It accounts for 13% of national employment and is the UK’s largest remaining manufacturing sector and its dependence on Europe is critical. A stark reality is that the UK only produces approximately half of what we eat and it is reliant on European imports for a quarter of our consumption.

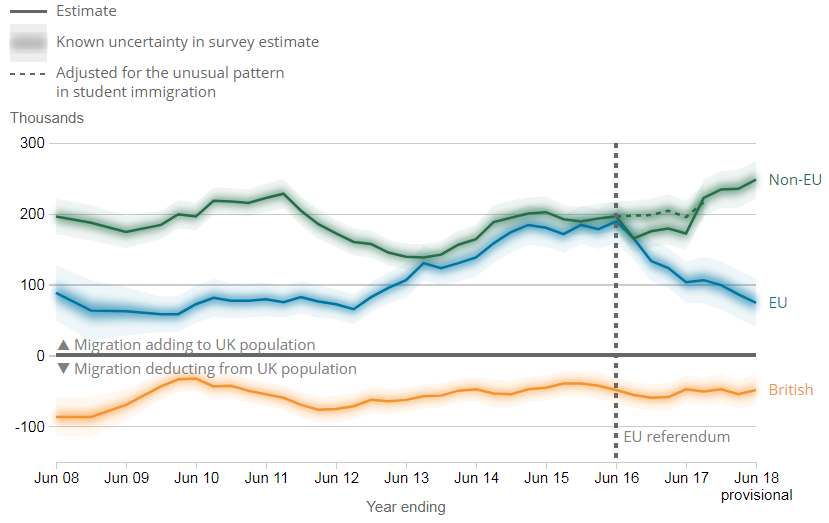

Secondly, if Parliament rejects May’s agreement with Brussels, the rights of millions of EU citizens in the UK and UK citizens in the EU may be called into question in terms of free movement and rights to work. Such a scenario has huge implications for the food and drink manufacturing, who have become heavily dependent on European migrant workers, so much so, that without them it could collapse as it employs over 3.8 million people. EU nationals contributed approximately 7% (2.2 million +/- 0.1 million) and non-EU nationals 4% (1.2 million +/- 0.1 million). Current statistics (see figure 1) indicate that the number net EU migration is the lowest since 2012, whilst net migration shows that 248,000 more none-EU citizens came to the UK than left in the year ending June 2018 and this was the highest non-EU migration since 2004.

Figure 1: Net migration by citizenship, UK, year ending June 2008 to year ending June 2018

The threats of Brexit are clear and present for the Food and Drink sector. They face a complex conundrum in trying to devise a viable strategy, as the Brexit waters are clearly uncharted. Questions remain unresolved about what guise future trading relations will take. They may have to manage within Economic Arena Arrangements, under a bilateral agreement or operate within World Trade Organisation agreements. Further unknowns, such as undefined customs boarders, the renegotiation of supply chains, adjusting to legislative and regulator requirements also cloud the future. Equally concerning is the diminishing food and drink work force in which it is witnessing a slow but steady exodus of its work EU employees resource base. In response, the food and drink sector is focusing on factoring out inefficiencies while there is evidence of stock piling ingredients to buffer potential product delays and in the scoping of relocation and recruitment feasibility studies. Despite efforts of being proactive, the future is at best fraught with unknowns.

Teresa May certainly appears isolated in her vision and wilting legacy. Her Brexit agreement has instigated a truculent House of Commons, fuelled rumours of a secret ‘Plan B’, threats to activate legal proceedings for contempt of Parliament, added growing momentum for a second peoples vote, whispers of a leadership challenge and an undercurrent from the Argentina G20 summit that Brexit is a bad deal for the UK. Thus, the potential outcomes have spiked speculation and anxiety for UK businesses. The clock is ticking towards December 11th “meaningful vote” on Theresa May’s Brexit deal and has generated suspense rather akin to the former BBC show ‘deal or no deal’ but the stakes and potential repercussions for the British food and drinks manufacturers are infinitely higher.

This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE Brexit, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Dr Derek Watson is a Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Business law & Tourism, University of Sunderland.

Is it possible that the £22bn pa UK-EU trade deficit in food might represent an opportunity for UK food manufacturers after Brexit, especially after a no deal Brexit?

Is it also possible that a small island using POPULATION GROWTH as the principle method of expanding business profits is at best short sighted and at worst clinically insane? (Migration adds between 0.5 and 0.8% pa to our population – most of the growth).