There is a significant difference in opinion on Brexit between different age groups in the UK, with older citizens generally exhibiting more negative attitudes toward the EU than younger ones. But as Kieran Devine writes, while over 65s are typically treated as a single category in opinion polls, there are substantial generational differences within this group, with those who lived through the Second World War being far more likely to oppose Brexit.

There is a significant difference in opinion on Brexit between different age groups in the UK, with older citizens generally exhibiting more negative attitudes toward the EU than younger ones. But as Kieran Devine writes, while over 65s are typically treated as a single category in opinion polls, there are substantial generational differences within this group, with those who lived through the Second World War being far more likely to oppose Brexit.

The EU was set up in response to the horrors and destruction of the Second World War. In the wake of the Brexit referendum result, it was oft repeated that the older generations were more likely to have voted for Britain to leave the European Union. This presents something of a puzzle; why would older generations, likely to have experienced the impact of the war first-hand, seek to remove Britain from an institution that has helped maintain peace in Europe for more than seven decades? Might it be that the ‘over 65s’ category, containing individuals several decades apart in age, conceals distinct generational differences amongst this group?

To address these questions, I have conducted an Age-Period-Cohort (APC) analysis using Eurobarometer survey data. APC analysis is used to ascertain if distinct generational effects are present in public opinion. Generational effects refer to the influence of environmental factors during each generation’s formative period (approximately between ages 15-25) on their long term political opinions, such as the prevailing social attitudes of the time or the occurrence of important political events. The Second World War is undoubtedly just such an event that may have deeply influenced the opinions of the generation that came of age during wartime.

This APC analysis used a longitudinal dataset of Eurobarometer surveys covering the years 1970-2017. These biannual surveys, consisting of 1,000 face-to-face interviews with members of the British public, ask respondents a range of questions, including their opinions on European integration. When controlling for a range of factors that have been identified as influencing attitudes towards integration – education, occupation, left-right position, gender, urbanisation – generational effects are confirmed in the data.

Specifically, when defining a ‘war generation’ that experienced the majority of their formative period during the Second World War, as well as a number of other more recent generations, this war generation is revealed as displaying significantly more positive views towards European integration than the immediate post-war generations. In fact, the size of this generational effect between the war and post-war generations is approximately equivalent to the same change in attitude that would be expected from a two-year reduction in education levels, a factor well known to increase Euroscepticism.

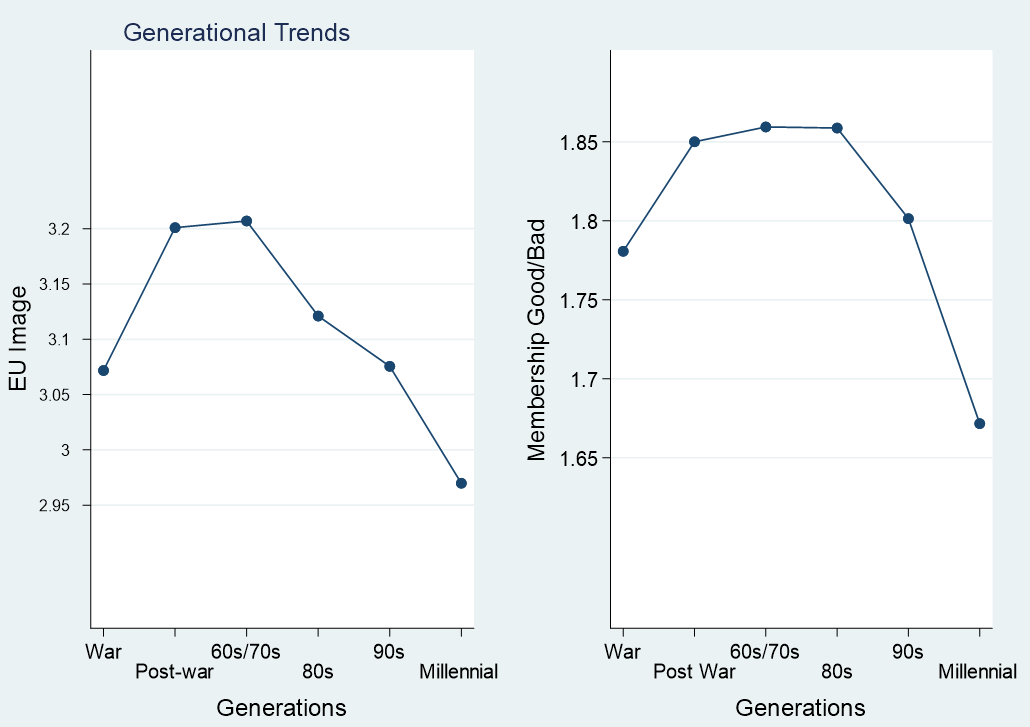

Holding all values at their mean in the data, Figure 1 illustrates the curvilinear differences in generational attitudes towards the EU in the UK. These results reflect respondents’ answers to questions regarding how positively they view the image of the EU, and whether they rate the UK’s membership of the EU as a good or a bad thing. In these illustrations, higher values connote more negative attitudes towards European integration. They therefore show that, all else being equal, the war generation have more positive attitudes towards the EU than the immediately following generations. Indeed, only the most recent generation, the millennial generation, display more positive attitudes towards the EU than the war generation.

Figure 1: Image of the EU among different generations in the UK

Note: For both charts, a higher value indicates a more negative image of the EU.

One explanation for these results is that the war generation give a premium to the pacific benefits of European institutions. Having experienced first-hand the horrors of war, they place a high value on the founding principles of unity that the EU promotes. The most recent generations also view integration more positively, given that these individuals have grown up with the UK’s membership of the EU as the norm. The concept of not being a part of Europe – with its visible signifiers of flags, anthems and institutions – is likely to be discordant to those from the millennial generation. Conversely, the post-war and 60/70s generations in the UK have neither the memories of wartime nor the routinised experiences of EU membership during their formative years. They therefore display the most hostile attitudes towards integration.

Additional variables, not captured in the Eurobarometer Survey data, appear poor alternative explanations for these findings. Reduced urbanisation, increased Protestantism, changes in party affiliation, the spread of communication technologies, and media frames have all been shown in previous research to affect attitudes towards European integration. This previous research, however, would suggest that the historical trends in these factors should lead to a reduction in hostility towards integration from the war to post-war generations. They are not, therefore, likely to be explaining the observed effects.

Including individuals’ responses to other questions in the Eurobarometer survey can more clearly outline the explanatory logics underpinning these results. Mediation analysis was performed on the answers to the question “What does the EU mean to you personally?” in the analysed models. Crucially, one of the 14 multiple choice answers to this question was “Peace”. If the observed effects were operating through the proposed ‘peace hypothesis’, accounting for those answering peace to this question should reduce the observed generational effects.

The results of this analysis confirm that this is the case: the older generations are more likely to associate the EU with bringing peace, and when mediating for these attitudes, the generational effects in the initial models are reduced by around 20%. The war generation are more likely to associate the EU with peace, and thus have more positive attitudes towards integration.

However, this analysis also reveals additional elements that are driving the cohort effects between the war and the following generations. Indeed, the post-war generation are in fact more likely to associate the EU with bringing peace than their younger counterparts, and yet they display more negative overall attitudes towards integration.

Conducting additional mediation analysis on alternative answers to the question of “EU meaning” reveals the importance of issues surrounding immigration and sovereignty to the post-war and 60s/70s generations. Almost 22% of the cohort effects are described by the post-war generation as being far more likely to associate the EU with a loss of control of the nations’ borders and a threat to national identity. Similarly, 45% is mediated by concerns surrounding a lack of the effective democratic functioning of the EU, something that has been linked in previous research to notions of an ‘anti-democratic’ EU eroding British sovereignty. It is thus not simply the scarring effects of wartime explaining the war generation’s positivity towards integration, but rather that the two following generations are also particularly hostile to European institutions.

Explanations for these results can be found in British history; the post-war and 60s/70s generations were the first to confront the fall of empire during their formative years, as well as the first mass immigration from the Commonwealth. This fuelled insecurities over British identity, coming to the fore in such instances as Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood Speech” and the Immigration Acts of the 1960s. These results therefore support the notion that it is during times when identities are threatened that they become mobilised as points of political salience, and that these heightened political environments can shape individuals’ opinions long into the future.

What do these results suggest for future UK public opinion on European integration? Firstly, extolling the virtues of the pacific benefits of the EU are likely to fall on ever more deaf ears – the generation with which this argument will have its greatest impact are severely dwindling in number. Secondly, the degree to which individuals feel their British identity is threatened may govern their level of positivity towards European institutions. Thirdly, the prevailing political environment shapes the long-term opinions of those in their formative years. Given the current ubiquity of the Brexit debate, today’s arguments and events surrounding integration will almost certainly have a significant impact on the most recent generation, namely those born after the millennium. In exactly what way these debates will shape public opinion, however, remains to be seen.

This post represents the views of the author and not the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain). It was first published on LSE EUROPP.

Kieran Devine is co-founder of the civic education social enterprise Connective Realities and holds an MSc in Comparative Politics from the London School of Economics.

I think there is a confusion betwee being pro EU and being European. My father, half German. many people who love Europe do not like what the EU has become.

You only have to watch the EU parliament in action to realisehow unpleasant and dismissive they are of the UK.

Ordinary people have suffered under the EU experimant.

We ar a country of suppressed wages, zero hour contracts poverty stricken seaside towns. .

London has done well because they provide Financial Services to Europe and ,make money on property related in the UK..The Government bail them out when the betting goes wrong..

The rest , manufacturing,and other businesses do not really matter when 80% of GDP is Financial Services.

No wonder much of the country voted Leave when being a member of the EU cartel facilitates this unbalanced economy..

You could say that the working population.voted Leave. It does not take long for young people to realise that after leaving university the real world hits them..

“Ordinary people have suffered under the EU experimant.”

“We ar a country of suppressed wages, zero hour contracts poverty stricken seaside towns. .”

You maintain that “people have suffered under the EU experimant,” but cite a series of ills which are in no way due to EU membership. No matter how dear to you your belief that the EU is responsible for these things may be, there has been a vast amount of research which shows that it simply isn’t the case. We have suppressed wages and zero hour contracts because our own laws and the way our own governments choose to manage the economy create the conditions where such practices are the norm, in particular by placing low-skilled workers in a position where they have negligible bargaining power with which to assert their claim to their share of profits. Have you never wondered why the UK is always so keen to opt out of EU legislation on social issues? Have you not noticed how more skewed is the distribution of income and wealth in the UK than in most other EU countries?

Sorry, but the supremely privileged advocates of Brexit have done a real number on you, persuading you that the EU, not your own government, is responsible for your relative poverty! Take a look at how real wages in the UK with it’s self-inflicted austerity policies have fared since the Global Financial Crisis, compared to the rest of Europe: only in bankrupt and crisis-stricken Greece have workers done anywhere near as badly as in the UK. If the plight of the low-paid in the UK is the fault of the EU, how have they done so much better in almost every other European country?

As for the rest:

“No wonder much of the country voted Leave when being a member of the EU cartel facilitates this unbalanced economy.”

Perhaps you haven’t noticed that one of the principal complaints of the Brexitists is that the EU Single Internal Market for SERVICES is under-developed (while in reality it is actually the most developed international market for services on the planet) and that the EU’s trade priorities disadvantage the predominant UK services sector. You are literally arguing two completely contradictory positions here.

Yes, London is certainly accorded vastly too much privilege, influence, investment and spending compared with the rest of the UK economy. If you think that Brexit is going to change that then I have a whole sack of expensive magic beans you will be delighted to buy!

Privileged people who have been taking the piss for decades have managed to delude the British people into believing that the problems they have caused by relentlessly exploiting the economy to their own advantage are all the fault of somebody else: the EU, immigrants, etc.

Once the UK has left the EU they will double down on immigrants; it will always be the fault of somebody else; working people will be told it is their own fault they are poor.

And now we have the conclusive evidence that a large part of the British public is (sorry) thick enough to buy this bullshit!

Charlie Aero .

Why would our London Governments bother with our seaside towns if they are not important to the Uk economy

Who mentioned immigrants,I didn’t!

You should not equate the two. I do not like UKIP .for their attitude on immigration.and I would never vote for such a party. .

My point is that our Governments did not have a clue about ordinary people’s lives.until this Brexit vote. The Governments of Rab Butler’s time.seemed to have had more care.

Some places in this country are much poorer that they were 40 years ago Being a member of the EU has not worked fo them..Membership has destroyed the Fishing for instance Nothing to do with immigrants, but certainly to do with membership of the EU..

There have always been immigrants. My daughter is taught to play the piano by a Polish concert pianist.. How lucky is that!

Immigrants add, and so do immigrants from other countries like the West Indies . Such people helped build the shattered country after the second world war..Why not immigrants from the Commonwealth or anywhere else.in the world. Why just the EU.

I do blame the EU,experiment for the troubles in our country and the troubles throughout Europe.and blame our Governments too.

I object to the fact that some far removed centralised European clique.can dictate rules.

As far as your comment on worker’s rights is concerned,,they have no relevance when there is little interesting work if any in some of these poor towns.,and zero hour contracts are the only jobs available.

One does not have to read propagander to realise that there is something wrong with the way things are in this country., you just need to see for yourself.and be less blind

You mention London, Yes i think some of the galss and steel super structures are brash an vulgar, and i am snobby about that, but in no way do i think London should be crushed… I think governments have failed to build prosperity elsewhere,in England because being part of the EU had not made this necessary. . .

.

Under developed areas is nothing to do with the EU, the politicians are to blame. And just for the record – this country was on its knees before we joined the EEC!

Like a ‘large part of the British public’ you seem to be unaware of the EU’s competition laws that drove the UK’s privatisation policies which in turn led to mass unemployment.in the UK’s industrial heartlands. Articles 86 and 87 of the Treaty of Rome. (TFEU 106, 107) are worth a look.

Given that European law also prohibits the right to operate a trade union closed shop (without which workers have little bargaining power), our membership of the EU has been a catastrophe for industrial workers.

It is sad that a ‘large part of the British public” know so little about EU law and its negative impact on industrial workers, but I’d hesitate to call them ‘thick’.Fortunately enough were sufficiently well-informed to vote leave.

There is no confusion: the data is about attitudes to the EU. People’s attitudes to continental Europe or countries within it are irrelevant.

The problems with ages, poverty-stricken towns, etc. are entirely products of government policy over the years. This has almost nothing to do with the EU. The EU works hard for things like workers’ rights and to reduce poverty. As a result of the appalling quality of the UK press, mainly owned by billionaires (many of them not British) the poorest areas, which have received the greatest help from the EU, voted against EU membership.

James , I think if there was a national need for seaside towns to be prosperous they would be. But why bother when theUK economy is doing well enough from London. My grandmother’s northeren seaside town was given a few crumbs of EU money to placate it,init’s poverty., but sadly it was used , so i heard, to dig up the sunken Italian Gardens and replace then with some ghastly windswept concrete area so as not to pay the garderners.. The gardens were put in during the 1920s so that there was a warm respite from the constant north wind..,They are a sad lost to the town and another dent in it;’s pride.having lost it’s Fishing industry.

Sorry James, the government privatisation policies that caused mass unemployment in industrial areas were nothing more than the enactment of EEC/EU competition law, particularly Articles 86 and 87 of the Treaty of Rome (106/107 TFEU), according to which socialism and Keynesian are outlawed. European law has also banned the closed shop. The handing over of fishing rights to the great European fleets has obviously also all but destroyed our fishing industry.

It is usually the level of knowledge or direct experience of of EU policies that determine attitudes. For those who have not suffered from its effects or know little about its laws and institutions, attitudes are likely to be the result of instinct or idealism and wartime experience certainly caused some to see the EU in idealistic terms. However it was principally set up by the USA as a bulwark against socialism so old socialists are less easily persuaded that it protects workers rights.

“Ordinary people have suffered under the EU experimant.

We ar a country of suppressed wages, zero hour contracts poverty stricken seaside towns. .”

None of which has anything to do with the EU. And claiming it does shows the recalcitrant resistance against facts and solid research that is so common to Brexiteers. The root cause being a falsely elevated self-image that precludes the very notion that the responsibility for anything bad could sit in little old England.

It has been shown time and time again that immigration does not suppress wages. But in the conflict between evidence and prejudice, you pick prejudice because what must not be cannot be.

“No wonder much of the country voted Leave when being a member of the EU cartel facilitates this unbalanced economy..”

Except the EU had nothing to do with that, either. If it did, it would be something that happened elsewhere, too. But manufacturing is alive and kicking in other countries.

“It does not take long for young people to realise that after leaving university the real world hits them..”

It does not take long for anyone with actual knowledge of the real world beyond the two steps out your front door to know you understand very little of the real world and make little effort to do so. Instead, you engage in antiintellectual propaganda, denying the validity of solid research and the value of academic effort – all the while you eagerly reap its profits.

Oliver.

I wish manufacturing was alive and kicking in England ,It is not, because we import much of what we need. and export Financial Services

This is Okay, but people need something worthwhile to do in their own towns..otherwise everyone will be pulled to London like Dick Wjhittington and his cat…

This is what I mean by an unbalanced economy. WHO MENTIONED IMMIGRATION! I DIDN”T.!.

There is little work in the town Ilive in. and what work there is is very poorly paid because the town is poor. Immigration is not an issue here.. .

“I think there is a confusion here between being pro EU and European”

There is no confusion at all. It is clearly discussed in the article:

“These results reflect respondents’ answers to questions regarding how positively they view the image of the EU, and whether they rate the UK’s membership of the EU as a good or a bad thing.”

So respondents were clearly being asked about, and responding to, questions regarding their attitudes to the EU and the UK’s membership of the EU. Unless you are suggesting that the respondents themselves were confused about what they were being asked – which I think is a little condescending.

I’m afraid Mrs Cheek your comment is very odd, but all too typical. Having identified correctly several things that are wrong with contemporary Britain, you then go on to blame EU membership for these problems. This is bizzaire, and it is why remainers do not comprehend your position.

Could you explain why you choose to blame the EU for home made problems? Or how Brexit would in any way address any of the problems you identify? No, of course you can’t.

The reality is the Brexit we are likely to get will make all of these issues worse, not better.

I’m afraid Mrs Cheek, in her comment, has the demographics wrong.

The biggest determiner of pro-EU/anti-EU stance is not age but university education. People who are university educated are much more likely to be supportive of the EU. There is, however, an indirect correlation because older generations are less likely to have benefited from a university education. (Those that did are also more likely to be pro-EU.)

This extends into most professions are well: scientists and engineers (one example) are overwhelmingly pro-Remain. I’d like to hope they’d be included in the category of ‘working population’.

Paul , i can only speak from personal experience.. I am on good friendly terms with both people who voted to Leave, and people who voted to Remain. All are university educated.. One ‘Leave’ is Croatian.!! . Work that one out!!

If you have a good London city job you are likely to vote Remain. If you live in some downdrodden seaside town you are likely to vote Leave..

I think you are saying that clever people voted to Remain and stupid people voted to Leave.When one prefixes’ I voted Remain ‘ to a comment it is really saying, I am a clever fellow.. In fact it is rather a stupid thing to say.because it puts up a barrier.

I think this attitude towards people whether they be university educated or not is unhelpful and it is also pointless

..

So Paul you think Scotland and Ireland are mostly university educated then……….?

I think you will find its down to trust ! We Scots (62% remain) and Irish(55.8% remain) do not trust the Westminster government 1 iota nor do we trust the right wing media that supports that government.

If its anything to do with education then its self taught in whom we trust.

Interesting. I had suspected this to be the case. Good that you conducted this research.

Thanks. Perhaps another area worth looking into could be the connection between any economists prevelent in the 1980’s who advocated the liberalisation of labour markets giving rise to practices like zero hours contracts, who then went on to advocate leaving the EU. I have come across at least one very influential one.

Amongst the war time attitudes, I’d be interested to know if there was much variation between civilians and those who saw active service?

It would also interesting if there was much variation between Privates and NCOs and Officers?

Lastly I’d like to know how the people likening brexit to the war, would feel if their blue passport came with a matching ration book?

THIS Baby-boomer (like a goodly number of my peers) is staunchly pro-EU!

Perhaps because I remember Ryanair trying desperately to defend through the EU courts it’s obnoxious attempt to heavily charge a disabled lady for her wheelchair at Stansted, & am now myself disabled.

Or perhaps because I love to travel, explore, meet other peoples, other solutions, other cultures.

Or because I was Union Rep for many years, and soon realised the benefits to YOUR case by working in harmony with others, not against them!

Also perhaps, because I believe that a united peoples-of-Europe front, is the last, & best hope to protect the people against the tyrany, arrogant, aloof fascism of the “Mill-owners, Pit-Owners, Aristocracy, Super-Rich & Royals” who like the Sun-King. Marie-Antoinette, Reese-Mogg & Old -Etonians everywhere” are happy to dine sumptuously, as we starve!

Well Said Believing in a United People’s of Europe front is best hope to protect. Plus you mentioned to protect us from the tyranny, and arrogant, aloof fascism of, Rees Mogg Dining Sumptuously as we starve.

This accords with polling done immediately after the referendum which showed that the majority of the 75+ age group voted remain.

Mrs cheek, what the hell are you prattling on about demográficos and education. The article is about people who suffered the effects of world war 2 being pro remain. It’s got nothing todo about north, south, economics or demographics, they are group commonly bound by having experience of the horrors of war not where they live or how much they earn!

I think this article is another veiled atack on people who dare question the wonder of the EU.The people who fought in both world wars have died or are very aged.

It is not safe when the discontennt of people rises up to war.. So perhaps in this sense, the Leave vote has saved the day. We would not want a people’s revolt to the extent there is a civil war.in this country .

There are some quite scary protests going on in France..

Please could you add the definitions of “war” and “post-war”.

Thanks

Prof Jonathan Kay

Hi Jonathan,

The war generation included those in the surveys born between 1920 – 1925. It is only people born in these years that will have experienced a majority of their formative years (defined as 15 -25) during wartime.

The post-war generation includes those born between 1926-1945, who experienced the majority of their formative years between 1946-1966, and thus experienced the post-war reconstruction and rise in living standards during their formative years.

Thank you

I need a bit of help with this! If the coming of age period is 15-25, does that mean that the ‘war generation’ consists of those who were 15-25 no later than 1945? So for the 60s/70s (say, 1965-1975) those who were 15-25 in that period? I was 15 in 1965 and (therefore!) 25 in 1975 and do not share at all the views of my cohort (not suprising in itself: these are average figures) but it does suggest that more work needs to be done on radical disparities of opinion within generations and therefore on dispositional factors. I’d suggest that coming of age during the later part of the 60s/70s was much different from coming of age during the earlier part, and I’d like to see more emphasis on closer, familial and local, factors. The Thatcher years split the country deeply, in my view, and more needs to be done on the consequences of those dreadful years on people’s formation. I’d also question such a broad brush as the 15-25 envelope, maybe.

Hi Nick,

The war generation included those in the surveys born between 1920 – 1925. It is only people born in these years that will have experienced a majority of their formative years (defined as 15-25) during wartime.

You’re right to point out that exactly how these ‘generational cuts’ are decided is open to dispute. It is a common point of debate in APC analysis. In regards to the war generation, this cut is quite clear, as it was a defined event with a start and end. The other generations were chosen as they match general societal changes (in relation to living standards, attitudes towards the church etc), but also changes in the UK’s relationship with the EU, which occurred at specific times, such as UK membership of the EEC. Given the disputed nature of these cuts, and the fact that some argue that a person’s formative years include ages outside of 15 – 25, I would suggest it is the trend seen across generations that is the key result of the research, rather than what it says about a ‘typical’ individual born in the 70s, for instance.

Hi Kieran – what is the sample size of this war generation that sits behind the data and what are the confidence intervals?

Hi there,

I am afraid I don’t have the data to hand right now, but it was several thousand for the war-generation when considering 1970 – 2017 (as you can imagine, they feature more heavily in the earlier surveys). The entire sample was around 24,000 individuals, if I remember correctly. Given the questions asked in Eurobarometer surveys were modified over time, these sample sizes can change significantly depending on which precise variables and question answers are included in the model. Regarding confidence intervals: regression analysis was done to compare differences between generations. When taking the war generation as the base generation, the differences to the post war generation are significant at just outside the 0.001 level, and with the 60s/70s generation at around the 0.01 level. With more recent generations the significance disappears, partly due to results becoming similar (as shown by the curvilinear shape of the graph), but also due to what essentially amounts to a reduced sample size – there are very few war generation people featured in recent surveys that can also be compared against the millennial generation. Of course, if you take the 60s/70s generation as your base, you get more insight into the difference between this generation at that in the 80s, for instance. In this case the war generation is the key one I was trying to measure.

Hi Kieran,

I’m a bit confused, if the right hand graph is good/bad, a high score means more not less love for the EU?

Hi David,

The higher the score on the graph, the more negative is the attitude towards the EU. This is simply due to the way the coding is done in the surveys. Those responding that they thought that the EU to be a good thing were scored as a 1, neither good nor bad a thing 2, and a bad thing, 3.

Please fix the poor English, i.e. “to the pacific benefits of European institutions.” And also what are the uncertainties in the plots?

Oh dear. Are you confusing ‘pacific’ with ‘specific’? I can see nothing wrong with the English used.

Thanks for an enlightening blog post, Kieran. Very important, given the Leaver tendency to falsely co-opt the war generation to their cause.

Interesting and surprising that many of the wartime generation support remain. The war was fought to preserve the sovereignty of this nation and thwart the attempts of subjugation to a foreign power by military might. Are they happy therefore to accept the selling of the same sovereignty, law making, etc, that has been achieved by political stealth, in exchange for a trade deal? Are there any other trade deals in the world that require member nations to progressively forfeit sovereignty and law making to a foreign power?

The war was fought to defeat the rise of the right wing fascism in Germany that was threatening the sovereignty of all European nations. The EU was set up post war to ensure that never happened again. Now we have a right wing government, being pushed even further to the right by other elements, trying to force us out of the EU based largely on the type of isolationist propaganda that was seen in Germany (and other countries) in the lead up to the war. Does that clear up any of your confusion?

Wealthy people typically live longer than poor people so the surviving war generation is likely to be wealthier on average than other generations. People from better off backgrounds are more likely to benefit from and favour EU membership so perhaps the survey tells us more about the relationship between class and life expectancy than it does about the wartime generation’s attitudes to the EU.

Born 1928 (90+) Oppose Brexit. Have said this since 2016!!!! I am war generation not postwar. Just do not understand Leavers..

Born 1928 (90+) I am not post-war generation – but war generation. Being at that time just on 11 years old, I can remember quite a lot. Including my father going off to France, and coming home from Dunkirk etc. I opp0se Brexit, and have done since 2016.

I couldn’t agree more. My father died in April this year, aged 93. He was articulate and very coherent to the end, and felt that the European community was one of the most positive outcomes of the war in which he had fought. Whilst -as an historian and also as an intelligent man – he had few illusions about the EU, in the context of an increasingly dangerous world of alliances and groupings, leaving one of the most successful and powerful in order to ‘stand alone’ was unbelievably foolish. His exact term was ‘economically and politically suicidal’.