The Prime Minister, Theresa May, has repeatedly asserted that Brexit is “the will of the British people”, and that the government, therefore, has a duty to “deliver” it. But is Brexit really the will of the British people? Christian List (LSE) takes a critical look at this question.

The Prime Minister, Theresa May, has repeatedly asserted that Brexit is “the will of the British people”, and that the government, therefore, has a duty to “deliver” it. But is Brexit really the will of the British people? Christian List (LSE) takes a critical look at this question.

The Prime Minister assumes that “the will of the people” is to be defined as “the will of the majority”. The 2016 referendum, which produced a majority for Brexit, can then be interpreted as showing that Brexit is indeed the will of the British people. And although the referendum was officially only advisory, it was widely treated as if it were binding, and so it may seem to justify Theresa May’s stand.

But there are several complicating factors. First of all, the majority was narrow. There were 17.4 million votes for Leave, 16.1 million votes for Remain, and 12.9 million abstentions. A further 18 million people living in the UK were not on the electoral register, including all young people below the age of 18 and many long-term residents who are not citizens, though they contribute to British society and have a stake in it. So, although 17.4 million is a large number, it is only a relative majority, not an absolute one.

Secondly, at the time of the referendum, there was no shared vision as to what “Leave” actually meant. As we now know, there are several different versions of Brexit, and it is not clear which one voters had in mind. This problem was exacerbated by the fact that the pre-referendum campaigns were arguably not as deliberative, honest, and respectful as one might have hoped in light of the gravity of the decision at stake, and some issues that subsequently became central, such as the border in Northern Ireland, were insufficiently discussed. A widely accepted principle is that high-stakes decisions require as much information as possible and especially careful deliberation. Many people feel that this principle was insufficiently adhered to in the case of the referendum. Some potentially undeliverable or misleading promises were made. Interestingly, the search phrase “What is the EU” spiked on Google after, not before, the referendum (see, e.g., here). This raises questions about whether the referendum result would have been the same if the pre-referendum debate had been more deliberative.

A third complication is that the referendum – even when taken at face value – gave us only a snapshot of people’s wishes in June 2016, and we cannot presume that these wishes remain unchanged. So, at most, it might be argued, Brexit was the will of the people at the time of the referendum. This raises the question of whether its mandate comes with an expiry date or whether it could continue to guide policy if there were a shift in public opinion.

But even if we set all of these complications aside, there is still a much bigger, but less widely recognized challenge for the view that Brexit is the will of the people. It lies in the fact that the majoritarian definition of the popular will, uncritically adopted by the Prime Minister and many others, is not generally coherent.

The point is an old one, first noted by Nicolas de Condorcet in the 18th century, but it remains valid today. Condorcet’s insight was that the preferences of the majority may be incoherent even when all underlying individual preferences are entirely coherent. For a simple example, suppose there are three options to choose from. Call them A, B, and C. Suppose a third of the population prefers A over B over C; a second third prefers B over C over A; and a final third prefers C over A over B. Then there are majorities (of two thirds each) for A over B, for B over C, and yet for C over A. Every option is defeated by another option in a pairwise majority comparison. None of the options can qualify as “the majority will” here – a problem known as “Condorcet’s paradox”. And so, if the will of the people is defined as the will of the majority, then there may not be a coherent such will at all.

More concretely, some commentators have suggested that once we recognize that the UK’s choice is not simply one between Leave and Remain, but between several options, such as Soft Brexit, Hard Brexit, and Remain, we might indeed be faced with an instance of Condorcet’s paradox (see, e.g., here and here). For instance, one third of the people might prefer Soft Brexit over Remain over Hard Brexit (thinking that Brexit should be delivered but Hard Brexit would have bad consequences); a second third might prefer Remain over Hard Brexit over Soft Brexit (thinking that Soft Brexit is the worst of both worlds); and a final third might prefer Hard Brexit over Soft Brexit over Remain (thinking that the harder the Brexit, the better). Then each of the options would be majority-defeated by another, just as in the earlier abstract example.

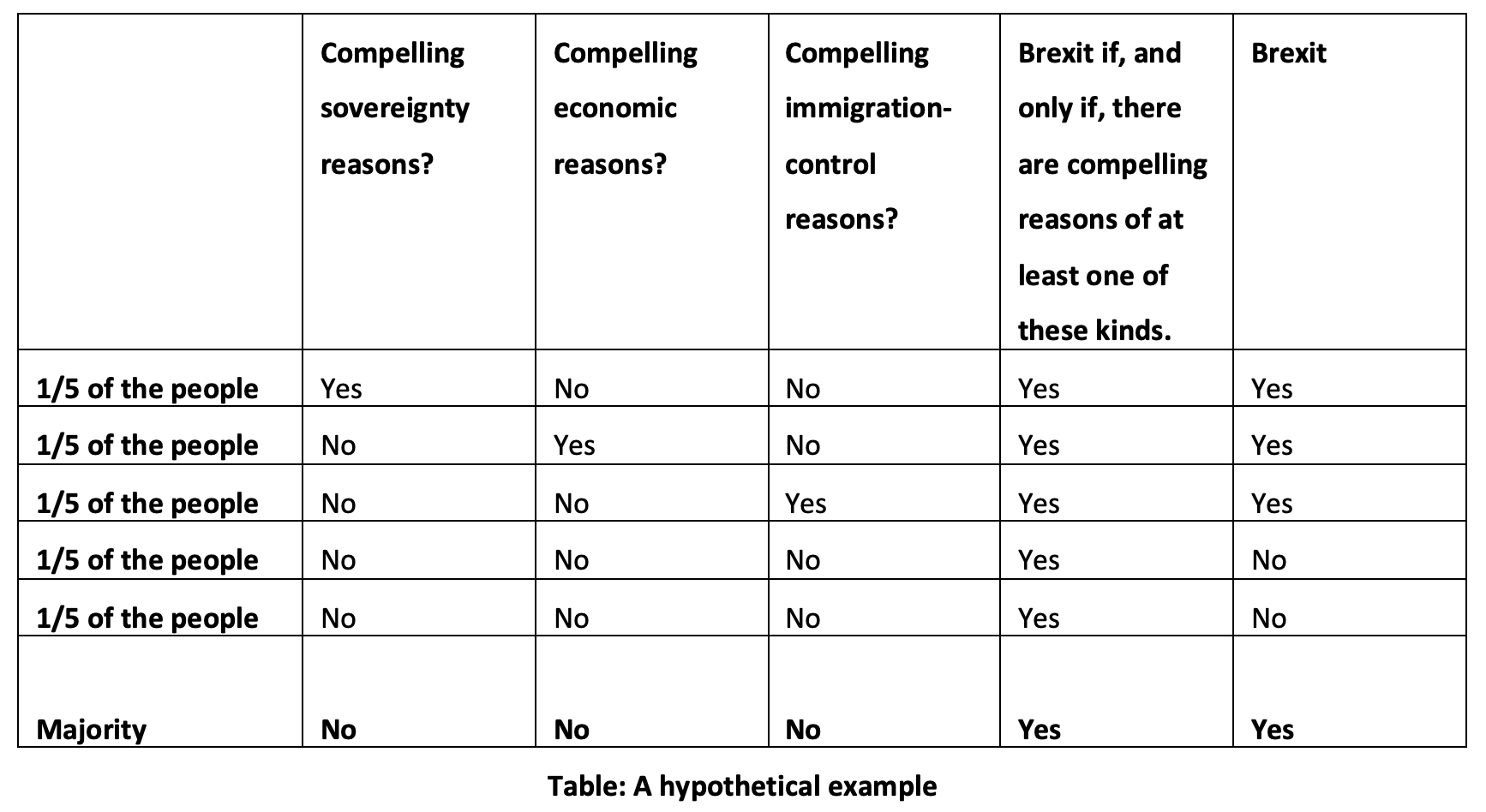

But even if we consider just two options, Leave and Remain, a certain kind of majority incoherence can still occur. We may wish to arrive not only at a majority decision on whether to pursue Brexit, but also at some reasons for that decision that are themselves accepted by a majority. The following hypothetical example shows that the overall package of majority opinions may still be incoherent. Let us assume, for the sake of this example, that it is generally agreed that Brexit should be pursued if, and only if, there are either compelling sovereignty reasons for leaving the EU, or compelling economic reasons, or compelling immigration-control reasons (or, of course, more than one of the above). Suppose now that the individual opinions in the population are as shown in the table below.

Then a majority does indeed think that Brexit should be pursued. But every one of the possible reasons for Brexit is rejected by a majority. And yet there is unanimous agreement that Brexit should be pursued if, and only if, there are compelling reasons of at least one of the three specified kinds. Clearly, the overall package of majority opinions is incoherent in this example. (This problem is an instance of a more general “paradox of inconsistent majorities”, as discussed here.)

Now, emphatically, this is a hypothetical example, which is not based on real-world opinion polls, and I am using it only to illustrate a conceptual point. But I don’t think that the scenario is entirely far-fetched. The relative majority for Leave in the 2016 referendum may well have been an “incompletely theorized” one (adapting a concept introduced by the legal scholar Cass Sunstein). By an “incompletely theorized majority opinion”, I mean one that is not supported by any publicly agreed reasons, but that is underwritten by a patchwork of different, perhaps mutually inconsistent individual considerations none of which rises to the level of majority acceptability.

More broadly, the examples I have given, beginning with Condorcet’s paradox, show that if we define the “will of the people” in majoritarian terms, we cannot be sure that there is a coherent will that can be ascribed to the people. Of course, the problem of majority incoherence may not come to the surface in every situation in which we are trying to merge individual opinions into collective ones. But from a conceptual perspective, the fact that the “majority will” may be incoherent even when all individual wills are coherent should give some pause to those who uncritically define the popular will as the will of the majority (a point made forcefully by William Riker in a classic 1982 book, Liberalism against Populism).

In my own social-choice-theoretic work, building on the ideas of others such as Kenneth Arrow and Amartya Sen, I have shown that we are faced with a major trade-off when we try to define any such thing as a “collective will”. Specifically, our definition of the collective will cannot simultaneously satisfy three initially plausible desiderata:

- “robustness to pluralism”, which says that the collective will should be well-defined irrespective of how much disagreement there is about it in the relevant society;

- “majoritarianism”, which says that the collective will should be defined as the will of the majority; and

- “collective rationality”, which says that the collective will should not be incoherent.

I have described this problem as a “democratic trilemma”: no more than two of the three desiderata can be met at once (see here). To see how the desiderata can come into conflict, recall the example of Condorcet’s paradox, where there is a majority for A over B, a majority for B over C, and a majority for C over A. In such a case, which can easily occur in a pluralistic society, it is impossible both to respect the majority views and also to arrive at a coherent collective will. Something has to give.

Any democratic society must engage in careful deliberation to figure out, for each context and each decision problem at hand, how it can construct its “collective will” in the most democratically justifiable manner. There is no one-size-fits-all solution. Ideally, we would not wish to sacrifice too much robustness to pluralism, nor systematically to overrule majorities, nor to live with incoherent collective decisions. But the relative importance of the three desiderata may vary from context to context, and in making democratic decisions, we must arrive at compromises that strike the best balance between the different desiderata, while remaining publicly justifiable. Simply reducing “the will of the people” to “the will of the majority” will not generally work.

How should we move forward in relation to Brexit?

For a start, we should refrain from attaching the loaded label “the will of the people” to the outcome of the 2016 referendum and instead recognize that it was an elicitation of votes, on a vaguely defined proposal, at a certain point in time, among a certain participating electorate, following a certain pre-referendum debate about which many concerns have been raised. Secondly, although we cannot deny that the chosen decision procedure was simple majority voting, we should also acknowledge that, on more careful reflection, requiring more than just a simple majority for a decision with such far-reaching consequences would have been desirable. Generally, there are strong democratic reasons for requiring supermajorities – such as two thirds or more – for any decisions of major constitutional significance. In fact, in many countries, constitutional changes can only be made with supermajority support, often in bicameral settings.

That said, the referendum has taken place, it has generated expectations, and we certainly cannot pretend that it hasn’t happened. Understandably, many Members of Parliament are reluctant to overturn it without a strong democratic mandate, even if they sincerely think that Brexit is against the national interest. This is one of the reasons why Parliament is so badly gridlocked. A second referendum could adjudicate the matter. If there were another referendum, however, it should be preceded by an extensive process of deliberation, a process that is as inclusive, information-based, reasoned, and respectful as possible, perhaps with citizens’ assemblies and similar events as key ingredients. Moreover, the process would need to look not only at Brexit narrowly construed but also at the broader challenges the country faces. Democracy requires more than just a mere counting of votes.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. For those interested in reading more about social choice theory and the notion of the will of the people, see, respectively, this survey article and this recent book. Image by Arnaud B., Some rights reserved.

Christian List is Professor of Philosophy and Political Science at the London School of Economics and a Fellow of the British Academy. In 2011, he published Group Agency: The Possibility, Design, and Status of Corporate Agents (with Philip Pettit).

Dear Sir,

Thank you for your enlightening analysis.

However, the British press does not come close to what you call “deliberation”. The Sun, the Times, the Telegraph, the Daily Express etc do not provide pluralistic opinions, let alone show any concern to minimize bias.

What is raging in the UK is close to civil war.

Brexit is not about economics or sovereignty or arguments.

It results from the desire for some general change of direction.

Many people have lost hope see that their socioeconomic status could improve if they just try hard enough. They feel that they have little to lose.

The furor is even justified, imho.

Why does nobody dare to address the austerity policy instead of distracting ourselves with tactical games and “humiliation”?

Those opposed to Brexit frequently remind us that the 2016 Referendum was only advisory. Well, the British electorate advised the government that they wanted to leave. But why would a government ask for the electorate’s advice if they were only to take it if they advised that we should remain in the EU? This really sums up a particularly twisted view of democracy.

The logical conclusion of this article is that democracy should be abandoned. A vote has no value a few days after it is held as people may have changed their minds. People may vote the same way for differing reasons eg Labour for taxation policy, spending plans or Jeramy’s beard so a GE with a Labour win should be put aside and the Conservatives placed in government?

The arguments in this article could be applied to any vote. I am curious if the author uses them after all votes or just the ones with outcomes he disagrees with?

Democracy in its FPTP format should most definitely be abandoned. It is no better than the tyrannical dictatorship of the majority ramming things through on their own efforts with zero incentives to compromise or let the minority side have a say in things. And the only thing expected to keep such a system in check is the cyclical swing from either side of the political spectrum to the other depending on who’s prevailing (Tory or Labour). And such a pendulum is most certainly broken when it comes to such a polaring single-issue as Brexit!

Mr List mentions en passant the insufficient discussion of the Northern Ireland border issue. However I think this element should be distinguished from the other reasons for casting doubt on the majoritarian approach to the brexit vote. My reason for saying this is that the Irish border issue vitally concerned a group of people whose views were not sought i.e. the electorate of the Republic of Ireland. The joint UK and Irish membership of the EU was a crucial part of the Good Friday Agreement. One of the sections of that agreement speaks of “close co-operation between the countries as friendly neighbours and as partners in the European Union”. It was only through that joint membership that the open border was possible.

Once the GFA had been entrenched by referenda North and South and registered with the UN as an international treaty, no UK government (or Irish government for that matter) had the right to give to its people unilaterally the decision to leave the EU. It is probably not feasible to establish this point in international law but the moral case is IMHO unanswerable.

Denis, the moral case is unanswerable indeed. The moral case for the GFA was also unanswerable. It is one of those things a country is saddled with. As people take a lifetime to get a little wiser, so a people take hundreds of years to get a little wiser. It could have been otherwise, but the facts are….

Things change. The people in the RoI found, if not liberty, at least sovereign independence for a while. Now they are in the EU, happily, on their way to become a statelet as part of a federal EU with no say in how they are governed. We know the drill. You can have a vote on anything you like and vote whatever you like, as a country, but if you vote the wrong way you have to vote again and again until you get it right, right for the EU Commissariat, that is, and if voting is too much bother for the authorities, the EU authority just goes on its merry way, ignoring what a nation-state voted for.

Brexit beats a GFA any time. It overrules it, in the first instance. If a country becomes a sovereign independent entity because its people voted out, there are always arrangements to adjust, treaties and agreements to sort out. The border issue was for the EU to sort out after Brexit. Renegotiating pre-independence arrangements, treaties and agreements is a matter for after, not before independence. For the UK to deal with these issues, it has to become a sovereign country first, before it can, as an independent entity, re-negotiate what must needs be re-negotiated. Though constitutionally out of the EU, due to the UK government the UK is not independent yet. The GFA may or may not need re-negotiating, but to bring a moral element into this matter is going too far.

Bliar was not a moral person. The IRA were and are not moral persons. The GFA was not a moral agreement.

Harking back to the basics, how can the future of one of the world’s (erstwhile) major countries, be decide upon, with merely the uneducated opinion of a barely 2% majority?

Firstly, it certainly was not binding.

Secondly, much less important matters are decided in modern democracies, such as the USA, the UK, and others, by demanding at least a 60/40 majority.

The whole business is barely democratic!

It almost has the stink of a dictatorship..

Yes, the entry of the UK into the then European Communities was illegal, of course. The 1975 referendum was also illegal because people didn’t get told what the plan was-to turn the economic community into a federal state. The 2016 referendum merely took the country back to the status quo of 1972.

Jacob, your comment here and the one above about the GFA display a wanton disregard of facts, despite your spurious reference to “the facts are…” when what you say contains virtually no facts.

The GFA is an International Treaty between the UK and Ireland. The change to how this treaty was envisaged and operates by the UK leaving the EU without provision for reconciling this (which is why there needs to be an Irish “backstop”) is not so much a moral issue, but an issue of bad faith and an abrogation of the treaty. The EU as a guarantor recognises this, shame that so many Brexiteers do not. As for calling peace in Northern Ireland “just one of those things a country is saddled with…”, denies a portion of the UK population their right to exist peacefully within our country.

The entry into the EEC in 1972 was not illegal, Parliament has the power to do this. The 1975 referendum was not illegal any more than the 2016 referendum was illegal. As to the “people didn’t get told…” nonsense in 1975, that is just a plain lie. The opposition to UK membership of the EEC was explicit about this and it was even talked about by “remainers” during that campaign.

Brexit, what it means and the choices it involves was glossed over on purpose by the Leave campaigns in 2016. They knew that if a choice had to be made about a plan for a post EU UK, they would never be able to agree and would lose. The campaign, such as it was, was fought on generalities and downright lies. The only reason that the result hasn’t been challenged in court is that it was an advisory referendum and has no force in law other than as a glorified opinion poll.

@David. Since I followed comments on The Guardian online for a year or thereabouts before I switched to the Daily Telegraph, I know the drift you’re following. Even on the DT your argument has been done to death, as, of course, here on this blog site. This here above your comment is not your first effort in that regard, if I remember correctly. International- and constitutional lawyers will no doubt sort it out. This is not the first time a country has chosen independence. Who knows how it pans out. We disagree on this, that much is certain, apart from your observation that the 2016 referendum was not illegal.

Re-Jacob Jonker. David is absolutely correct in his arguments, and you show a typical Europhobic paranoia about the EU Commisariat. I was around at the time of the 1975 referendum and it was very clear that being a member of the EU was both economic and political. That was not hidden. If you read the official government history of the UK’s entry into into the EEC as it was then, written by Sir Patrick Wall, that is absolutely clear.

“with merely the uneducated opinion of a barely 2% majority?” What the blazes has the level of education got to do with it? Should we go back to pre-1945 days, when graduates of certain universities got additional representation in parliament? Do we believe in democracy or rule by an educated elite?

As for the 2% argument, 52% is not much, but it is more than 48%. What gives the 48% the right to boss over the 52%?

As a retired civil servant with a statistical background, I’m afraid that most (though not all) either lack the numeracy or the numeric confidence to grasp the sound rationale you present. I found there were 3 reasons why ministers made decisions:

Ideology,

Pressure (from colleagues media or constituents)

Evidence.

We collated and evaluated the evidence. They made their judgment and decided.